Robert Rauschenberg

Robert Rauschenberg

1925 - 2008

American painter, sculptor, printmaker, photographer, and performance artist. While too much of an individualist ever to be fully a part of any movement, he acted as an important bridge between Abstract Expressionism and Pop art and can be credited as one of the major influences in the return to favour of representational art in the USA. As iconoclastic in his invention of new techniques as in his wide-ranging iconography of modern life, he suggested new possibilities that continued to be exploited by younger artists throughout the latter decades of the 20th century.

1. Training and early work, to 1953.

Rauschenberg studied at Kansas City Art Institute and School of Design from 1947 to 1948 under the terms of the GI Bill before travelling to Paris, where he attended the Académie Julian for a period of about six months. On reading about the work of Josef Albers he returned to the USA to study from autumn 1948 to spring 1949 at BLACK MOUNTAIN COLLEGE, where he was taught by Albers and his wife Anni Albers; he moved in spring 1949 to New York, where he attended the Art Students League until 1952. During this period he continued to visit Black Mountain College, where he came into contact with members of the department of music and dance, in particular JOHN CAGE and MERCE CUNNINGHAM, who helped shape his own ideas and in particular his reliance on chance methods, daily experiences and found material as elements of his art.

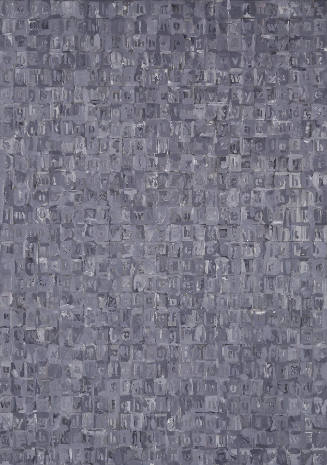

In the early 1950s, just as Abstract Expressionism was being recognized as the most important avant-garde movement to have emerged in the USA, Rauschenberg produced several series of abstract paintings: a group of White Paintings (1951; e.g. artist’s col., see 1980–81 exh. cat., p. 259), followed by Black Paintings (1951–2; e.g. artist’s col., see 1976–8 exh. cat., p. 67) and Red Paintings (1953; e.g. Beverly Hills, CA, Frederick R. Weisman priv. col., see 1976–8 exh. cat., p. 75). His concern, however, was not so much to project his personality through the individuality of the brushwork, as in action painting, but to present the textured surfaces of these essentially monochromatic works as screens whose appearance changed in response to the lighting conditions and the shadows cast on them by the spectators.

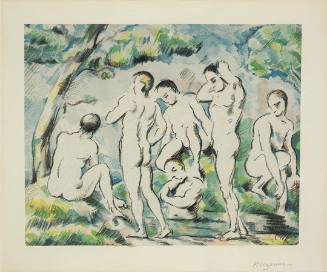

The first of Rauschenberg’s monochromes, some of which were painted on multiple panels measuring over 3 m in width overall, were made as backdrops for dance performances. While their austerity of form prefigures Minimalism of the 1960s, they were thus conceived largely in relation to the human figure. Rauschenberg’s importance and influence, in fact, were centred from the beginning on the highly original ways in which he reintroduced recognizable imagery. From 1949 to 1951 he and his wife, Susan Weil, whom he had met as a fellow student in Paris and married in 1950, produced a group of large-scale monoprints by shining a sun-lamp over a nude model resting directly on blueprint paper; Female Figure (Blueprint) (2670×910 mm, c. 1949; artist’s col., see 1980–81 exh. cat., p. 57) is one of the most imposing of these works. In combining elements of photography, printmaking, and painting in a single image, these experimental works presaged the deliberate blurring of the boundaries between different media that quickly became one of the characteristic features of Rauschenberg’s art.

A desire to assimilate but also transcend the lessons of Abstract Expressionism was a strong motivating force in Rauschenberg’s early work. In a collaboration with John Cage, Automobile Tire Print (ink on paper mounted on canvas, 420×6720 mm, 1951; artist’s col., see 1976–8 exh. cat., p. 65), he elaborated two of the movement’s essential concerns—that of revealing the process by which the marks are made and of working on an environmental scale—while simultaneously parodying them and stripping them of their pretensions to grandeur and sublimity. Instead of suggesting that the marks are the result of an existential struggle between the artist and his or her materials, he presents the imprint made by a car driven into wet ink and then on to the paper; the extensive scale similarly functions on an equally literal, even banal, level, as the image as a whole can be apprehended only through the spectator’s actual movement over a period of time.

2. Combine paintings and transfer drawings, 1954–61.

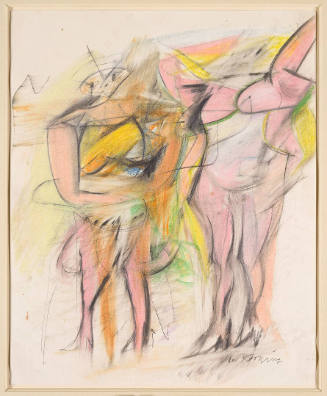

In 1953 Rauschenberg asked Willem de Kooning for a substantial drawing with the express intention of rubbing it out so that only faint traces of the original could be seen. While this act (Erased de Kooning Drawing; artist’s col., see 1976–8 exh. cat., p. 75) of simultaneous homage and sabotage towards one of the most esteemed artists of the time has generally been seen as a sign of Rauschenberg’s debt to Dada, his purpose was not to make an anti-art gesture but to open up the possibilities about what art could be.

Among the Dadaists Rauschenberg’s greatest affinity was with Kurt Schwitters, whose Merz collages had suggested the possibility of finding beauty through the retrieval of refuse and humble materials gathered together while wandering the streets. In 1954 Rauschenberg began to produce paintings such as Charlene (1954; Amsterdam, Stedel. Mus.), which combined objets trouvés, postcards, and other printed materials into a frantic and physically substantial surface as a way of alluding to what he referred to as the ‘gap’ between art and life.

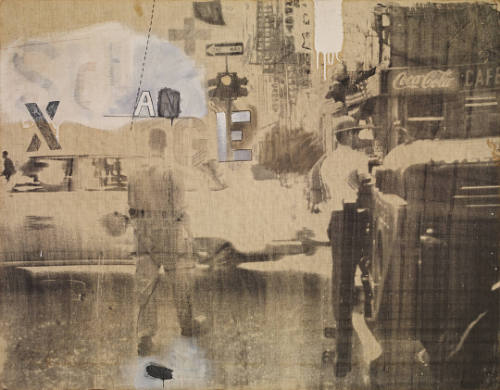

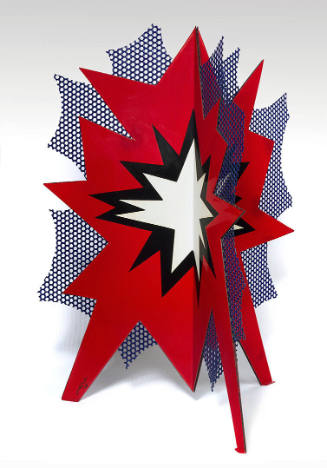

Rauschenberg called these works ‘combines’ because of their mixture of techniques, but at their most sculptural it was clear that their debt was to traditions not only of collage but of ASSEMBLAGE (see fig.). Their reliance on discarded materials and frequently squalid appearance made them influential examples of JUNK ART, especially in the case of free-standing works such as Odalisque (1955–8; Cologne, Mus. Ludwig). Certain works, such as Bed (1955; New York, MOMA), executed at the same time as the paintings of flags by Jasper Johns, who had a studio in the building also occupied by Rauschenberg from 1955 to 1958, influenced the emergence of POP ART in their identification of the work of art with a real object.

Rauschenberg used great ingenuity in alluding to personal and shared experiences. There is often a sense that his works are to be regarded as collaborative ventures with the spectator, as in Black Market (1961; Cologne, Mus. Ludwig), which consists not only of a painting but also of a suitcase containing objects meant to be used by the viewer in completing the work. Another ‘combine’, Pilgrim (1960; Berlin, R. Onnasch priv. col., see 1976–8 exh. cat., p. 110), consisting of a paint-smeared chair resting against a broadly painted canvas, relates to a black-and-white photograph he took in 1949, Quiet House—Black Mountain (see Robert Rauschenberg Photographs, pl. 1), in which a shaft of light falls across one of two chairs seen frontally against a bare wall.

During this period Rauschenberg also developed a transfer drawing technique, by which he dissolved printed images from newspapers and magazines with a solvent and then rubbed them on to paper using a sharp pencil. The process allowed him freely to combine images from a variety of sources on a single surface. He used it to particular effect in a series of 34 Drawings for ‘Dante’s Inferno’ (1959–60; New York, MOMA). The methods of free association by which he built up these compositions, indebted in part to Surrealism, remained an essential ingredient of his later art.

3. Screenprinted paintings and installations, 1962–70.

Rauschenberg stopped making combine paintings in 1962, when he found a way of adapting his method of transfer drawing to canvas by applying found images through the photomechanical process of screenprinting. Often he painted over this printed surface in oils, for example in Estate (1963; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.), and he remained interested in textural effects and in apparently spontaneous methods of organizing his imagery, which gave these works a more personal touch than that sought by Andy Warhol in his screenprinted paintings of the same date. It was nevertheless in these works and in editioned prints, such as Breakthrough II (colour lithograph, 1965; New York, MOMA), that he came closest in spirit to Pop art.

Rauschenberg won, with some controversy, the grand prize for painting at the Venice Biennale in 1964, but after that date his interest shifted from painting to performances and more elaborate sculptures and installations. Until 1965 he travelled with Merce Cunningham’s company, for which he had designed sets and costumes from 1954 and acted as lighting director and stage manager from 1961. He staged his own performances from 1963, with the première of Pelican, which he choreographed and designed, through to 1967. The dramatic aspects of these live events were translated into sculptural installations such as Oracle (1965; Paris, Pompidou), a ‘sound environment’ consisting of five motor-operated objects.

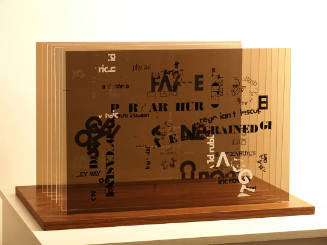

The battered appearance of such works, still aligned with junk art, soon gave way to more elegant and pristine installations. Soundings (2.44×10.97×1.37 m, 1968; Cologne, Mus. Ludwig), for instance, consists of three rows of nine Perspex panels, each with screenprinted photographs of chairs taken from different angles; electric lights within the work are activated by sounds made by visitors in a darkened gallery, encouraging prolonged applause in a deft metaphor rewarding the artist for his performance.

4. Works after 1970.

In the early 1970s Rauschenberg embarked on Cardboard Series (e.g. see 1986–7 exh. cat., pp. 27–31), each of which consists simply of the configurations created by opening out the sides of cardboard boxes and laying them flat against the wall. Like the Arte Povera artists working at that time in Europe, he stressed the ordinary and humble quality of his materials in an even more exaggerated manner than had been the case in his earlier work; these constructions, however eccentric and complex in form, contain no additional handmade or painted marks. In calling attention to the creative act as the restructuring of an objet trouvé, they take as their theme the process by which they have been called into being. In this they were also aligned with developments of the time, particularly with PROCESS ART.

In 1974 Rauschenberg began his Hoarfrost Series (e.g. see 1986–7 exh. cat., pp. 33–7), which consists of layers of transparent gauze-like fabric laid over each other like veils and combined in some cases with more substantial collage elements. His use here of soft materials that find their form only when hung on the wall again relates to aspects of process art, such as the felt pieces made by Robert Morris (ii) in the late 1960s, while synthesizing aspects of his own earlier art into works of extraordinary delicacy and subtlety. There is a suggestion in particular of the evanescent quality of images momentarily imprinted on our consciousness: the photographic images are drawn from a variety of sources and impregnated into the cloth by solvent transfer, a technique adapted from the drawings he had made from the late 1950s and casually related to each other by collage-like methods of composition.

In later works Rauschenberg continued to develop the principles on which he had operated from the 1950s, frequently combining elements of painting, sculpture, photography and printmaking with such thoroughness as to make redundant the conventional demarcations from one medium to another. In Spray Shield Marathon (1977; Aachen, Neue Gal.), for instance, images are impressed on to the back of a sun tent hung parallel to a sheet of polished aluminium, so that they can be seen only in reflection, while in Suzerain (1979; Mainz, Landesmus.) a plethora of images is printed or collaged on to canvas and on to a wooden panel mounted on to a movable sculptural object placed on the floor.

While Rauschenberg did not create any radically new directions in the 1980s, he continued to develop provocative variations on his standard methods, notably in a series of wall-mounted works entitled Gluts (see 1987 exh. cat.) that were assembled from found pieces of crushed or battered metal. The extended series of works that he devised around the world from 1985 to 1990 as part of an ambitious project, the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange, revealed the extent to which he continued to regard his art as an agent of social interchange and communication. In these and other works of the period he demonstrated conclusively that he had lost none of his ability to bring together images, shapes, and textures with an unerring intuitive grasp of their interrelationships. Having long since escaped the confines of style, as understood by most artists of his generation, and even the distinction between abstract and representational art, he recognized no rules other than those he had himself invented as the basis for his art. [Marco Livingstone. "Rauschenberg, Robert." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 10, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T070888.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms