Alfred Stieglitz

Alfred Stieglitz

1864 - 1946

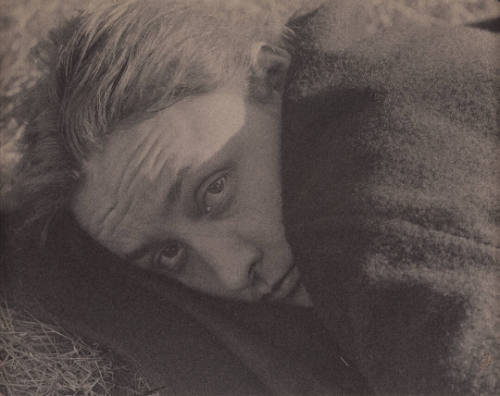

American photographer, editor, publisher, patron and dealer. Internationally acclaimed as a pioneer of modern photography, he produced a rich and significant body of work between 1883 and 1937 (see fig.). He championed photography as a graphic medium equal in stature to high art and fostered the growth of the cultural vanguard in New York in the early 20th century.

1. Life and works.

(i) Formative period in Germany, 1881–90.

The first of six children born to an upper-middle-class couple of German–Jewish heritage, Stieglitz discovered the pleasure of amateur photography after 1881, when his family left New York to settle temporarily in Germany. His father, Edward Stieglitz, had retired from a successful business in the wool trade with a fortune that enabled him to educate his children abroad. In 1882 Alfred enrolled in the mechanical engineering programme of the Technische Hochschule in Berlin, but he spent his spare time experimenting with photography in a darkroom improvised in his student quarters. His self-directed experiments led him to study photochemistry with the eminent scientist Hermann Wilhelm Vogel, who taught him the scientific bases and technical principles of photography. Building on this scientific knowledge, Stieglitz decided to pursue serious photography. He absorbed artistic influences from 19th-century painters working in the style of the Barbizon school and, more significantly, from English photographers, notably P. H. Emerson. Rejecting the sentimental subjects and manipulated prints of Victorian and pictorial photography, Emerson instead advocated ‘truth to nature’ in straight photography that captured the appearance and atmosphere of the visible world by respecting the integrity of the photographic medium. Stieglitz owed many of his ideas, as well as his early use of platinum paper for printing and photogravure for reproduction, to Emerson’s example. In 1887 Emerson awarded Stieglitz first prize for A Good Joke (Washington, DC, N.G.A.), one of a group of Italian photographs submitted to a competition sponsored by the English journal Amateur Photographer. Stieglitz’s Sun Rays—Paula (1889; Chicago, IL, A. Inst.), an early silver print of a young woman writing in an interior illuminated by slatted blinds, revealed his technical mastery of composition and tonal range.

(ii) New York, 1890–1901.

Although he would have preferred to remain in Germany, Stieglitz returned to New York in 1890. Complying with his parents’ wishes, he entered a photo-engraving business in partnership with the friends with whom he had lived in Berlin, and in 1893 he married Emmeline Obermeyer (1873–1953), the sister of one of them. During the 1890s Stieglitz used his hand-held camera to capture candid scenes of New York life. The Terminal (1893; Washington, DC, N.G.A.), a photogravure of a street-car driver watering down his horses, and Winter on Fifth Avenue (1893; Rochester, NY, Int. Mus. Phot.), the first pictorial photograph of a snowstorm, anticipated the frank treatment of working-class urban subject-matter by such Ashcan school painters as John Sloan in the following decade. Working outside at night, Stieglitz photographed the Savoy Hotel after a rainstorm in Reflections—Night, New York (1896; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.). During his honeymoon abroad in 1893–4 he produced prize-winning photographs of Venice and the Netherlands. Throughout the 1890s his photographs won prizes in British and European competitions and earned him an international reputation.

In 1895 Stieglitz left the photo-engraving business to pursue photography full-time. For years thereafter, his father paid him an annual allowance. Serving from 1892 to 1895 as editor of the American Amateur Photographer, Stieglitz determined to crusade for the improvement of American photography. In 1896 he helped merge the Society of Amateur Photographers with the New York Camera Club to form the Camera Club of New York. As its vice-president and editor of its quarterly publication, Camera Notes, from 1897 to 1901, he tried to bring American photography into the international arena.

(iii) Photo-Secession, 1902–17.

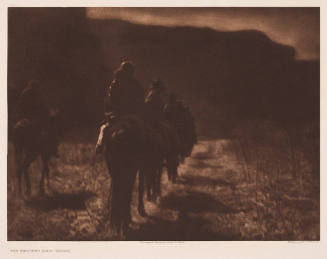

In February 1902, after the growing progressive movement in American photography provoked conservative opposition within the Camera Club, Stieglitz founded an alternative group concerned with PICTORIALISM, the PHOTO-SECESSION, loosely modelled on the English Linked Ring and European Secessionist groups. In March he organized an exhibition, American Pictorial Photography, at the National Arts Club in New York to introduce the new group. EDWARD J. STEICHEN, a friend and also a prominent photographer, helped formulate their goals: to promote photography as ‘applied pictorial expression’, to unite progressive American photographers and to sponsor exhibitions of members’ works. In 1903 Stieglitz published the inaugural issue of CAMERA WORK, the journal that served for the next 14 years as the organ of the Photo-Secession and as the platform for his aesthetic programme; see The City of Ambition, 1910. Its contents ranged from technical articles on photography to essays on aesthetics, literature, criticism (particularly Symbolist and modernist theories) and modern art. Lavishly illustrated with superb photographic reproductions, Camera Work included essays by such photographers as Steichen and Alvin Langdon Coburn, such writers as Gertrude Stein, such critics as Charles Caffin (1854–1918) and Sidney Allen (pseud. of Sadakichi Hartmann), and artists such as Max Weber and the Mexican illustrator Marius De Zayas. In quality of printing, reproduction, typography and design, Camera Work embodied Stieglitz’s rigorous aesthetic standards.

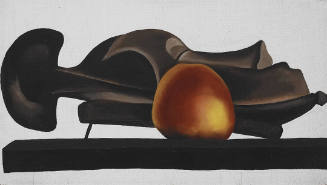

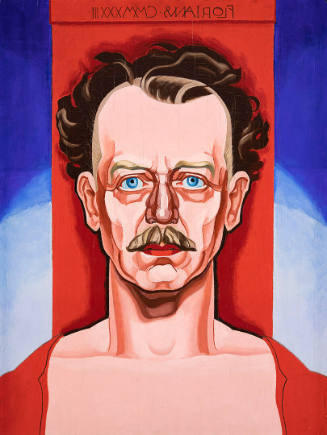

Between 1902 and 1904 Stieglitz arranged Photo-Secession exhibitions throughout Europe and across North America. In November 1905, with Steichen’s assistance, he opened the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession on the top floor of 291 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. Later known simply as 291, the gallery displayed selections of Pictorial photography and became the headquarters of the Photo-Secession. With Steichen’s help, Stieglitz began to show contemporary art at 291 in 1907 and was the first in the USA to present works by such European modernists as Henri Matisse (1908 and 1912), Paul Cézanne (1911), Pablo Picasso (1911) and Constantin Brancusi (1914), as well as African sculpture as art (1914–15). The gallery also actively supported art by the American pioneers of modernism, notably Oscar Bluemner, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Elie Nadelman, Georgia O’Keeffe and Max Weber. Under Stieglitz’s direction, 291 became a meeting-place and focal-point for the New York avant-garde. In 1915 a group of his followers, including De Zayas and the patron Agnes Ernst Meyer (1887–1970), opened the Modern Gallery and began publication of the vanguard journal 291, intended to augment Stieglitz’s efforts. Stieglitz, for his part, demonstrated his support for the New York Dada movement by photographing Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, a urinal presented as a ready-made, when it was rejected in 1917 for the first annual exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists.

The scope of Stieglitz’s activities as publisher, patron and gallery owner necessarily diminished the quantity, though not the quality, of his own photographic output during this period. He continued to record New York and repeatedly photographed the view of buildings from the back window of 291 (see fig.). He also produced a remarkable series of character studies: portraits of the artists, critics and friends of the 291 group. During this period he created one of his most enduring images, The Steerage (photogravure, 320×257 mm, 1907; Washington, DC, N.G.A.), a masterfully composed picture of a ship filled with prospective immigrants to America returning to Europe. Exhausted by his manifold efforts on behalf of modern art and photography, Stieglitz closed 291 and ceased publication of Camera Work in 1917.

(iv) New York and Lake George, 1918–46.

With the end of the Photo-Secession, Stieglitz devoted more time to his own photography. He continued to live and work in Manhattan and regularly spent the summers on the Stieglitz family property in Lake George, NY. In 1918 he invited GEORGIA O’KEEFFE to return to New York from Texas in order to pursue her career. Long unhappy in his marriage, he separated from his wife and began living with O’Keeffe, marrying her in 1924, after his divorce. O’Keeffe provided the inspiration and subject for an important group of Stieglitz’s mature photographs. Over a twenty-year period, he created a serial portrait of her in hundreds of studies that were among his most deeply felt and original contributions to modern photography. Equally daring was his series of virtually abstract photographs of clouds, collectively known as Equivalents (1922–9; see fig.), such as Music: A Sequence of Ten Cloud Photographs, No. 1 (1922; Washington, DC, N.G.A.). Stieglitz believed that the moody and ethereal patterns he recorded by turning his camera skyward mirrored his own emotional states. He designated this expressive theory ‘idea photography’. In the spring of 1924, Stieglitz gave two dozen of his photographs to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the first American institution to accept photographs for its graphic art collections.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s Stieglitz habitually photographed the buildings and scenic landscape surrounding his family property in Lake George. His images of old barns in winter and ageing poplar trees combine the simplicity of direct observation with the emotional intensity of long familiarity with such cherished sites. In 1930 Stieglitz began a final series of photographs of New York as seen from the window of his last gallery, An American Place, which he ran from 1929 to 1946, or from the window of his flat at the Shelton Hotel, for example From the Shelton Westward–New York (1931–2; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.) and Looking North-west from the Shelton, New York (1932; New York, Met.). Documenting the construction and transformation of the city, these late prints displayed a greater sense of geometric order akin to the paintings and photographs of the Precisionists. In 1937 Stieglitz, plagued by heart trouble, could no longer lift his cameras and stopped taking photographs.

Throughout his later career Stieglitz continued to champion a smaller group of American artists and photographers, chiefly O’Keeffe, Dove, Hartley, Marin and Paul Strand. He arranged special exhibitions of their work and his own photographs in New York at the Anderson Galleries from 1921 to 1925, and in 1925 he opened the Intimate Gallery, which remained in operation until 1929, to promote their paintings and photographs. Less concerned with European modernism in his later years, Stieglitz instead advocated a brand of cultural nationalism embodied in the name of his last gallery, An American Place, which after his death continued to be operated by O’Keeffe until its closure in 1950. Stieglitz left an important collection of his own and his fellow photographers’ work, as well as an equally significant collection of modern art. O’Keeffe donated the key set of Stieglitz’s photographs to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, and distributed his art collection and photographs to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Art Institute of Chicago; the Museum of Art in Philadelphia; and Fisk University, Nashville, TN.

2. Working methods and technique.

Stieglitz’s methods reflected his commitment to ‘straight’ photography. Opposed to ‘dodging’ and retouching, he carefully selected and framed his subjects, thereby composing his images directly through the camera lens on to the glass plate negative. He preferred to use a sharp focus and generally refrained from editing or manipulating his prints. Homer (1983) discovered variant states of well-known early photographs among the key set in the National Gallery of Art. While these variations revealed that Stieglitz occasionally cropped images to achieve a desired composition, such departures from ‘straight’ photography were not part of his usual practice. Around 1898, together with another American photographer, Joseph T. Keiley (1869–1914), Stieglitz devised a method to control development by coating the exposed platinum print with glycerin to produce the effect of a wash drawing. Stieglitz experimented briefly with this more pictorial technique. As the leader of the Photo-Secession, he exhibited and supported the work of photographers who used a soft focus or other pictorial methods, but for his own work he restricted the range of control as much as possible to the camera rather than to the printing process.

A perfectionist more than a technical innovator, Stieglitz extended the expressive limits and power of existing photographic techniques. He was a meticulous craftsman who insisted on the best equipment and materials for his photographic work. For printing, he preferred to use a high-quality platinum paper imported from England, until its prohibitive cost ended its commercial manufacture in 1916. During the 1890s he demonstrated the artistic potential of lantern slides when he produced high-quality reproductions of his photographs by this method. Most of his mature photographs were printed shortly after the negatives were made; however, between 1917 and 1932, he periodically reprinted earlier negatives from the 1880s and 1890s. [Judith Zilczer. "Stieglitz, Alfred." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 11, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T081415.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms