James McNeill Whistler

James McNeill Whistler

American, 1834 - 1903

American painter, printmaker, designer and collector, active in England and France. He developed from the Realism of Courbet and Manet to become, in the 1860s, one of the leading members of the AESTHETIC MOVEMENT and an important exponent of JAPONISME. From the 1860s he increasingly adopted non-specific and often musical titles for his work, which emphasized his interest in the manipulation of colour and mood for their own sake rather than for the conventional depiction of subject. He acted as an important link between the avant-garde artistic worlds of Europe, Britain and the USA and has always been acknowledged as one of the masters of etching (see ETCHING, §V).

From his monogram jw, Whistler evolved a butterfly signature, which he used after 1869. After his mother’s death in 1881, he added her maiden name, McNeill, and signed letters J. A. McN. Whistler. Finally he dropped ‘Abbott’ entirely.

1. Life and work.

(i) Early life, 1834–59.

The son of Major George Washington Whistler, a railway engineer, and his second wife, Anna Matilda McNeill, James moved with his family in 1843 from the USA to St Petersburg in Russia, where he had art lessons from a student, Alexander O. Karitzky, and at the Imperial Academy of Science. In 1847 he was given a volume of WILLIAM HOGARTH’s engravings, which made a great impact on him. In 1848 he settled in England, attending school near Bristol and spending holidays with his step-sister Deborah and her husband, the collector Seymour Haden, who sent Whistler to Charles Robert Leslie’s lectures at the Royal Academy, London, and showed him his Rembrandt etchings. William Boxall painted Whistler’s portrait (exh. RA 1849; U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.), showed him the Raphael cartoons at Hampton Court Palace and gave him a copy of Mrs Jameson’s Italian Painters (1845).

After Major Whistler’s death in 1849, James returned to America and entered the US Military Academy, West Point, NY, in 1851. At Robert W. Weir’s classes he copied European prints. He also produced caricatures and illustrations to Walter Scott and Dickens, influenced by PAUL GAVARNI and GEORGE CRUIKSHANK. Whistler’s first published work was the title-page of a song sheet, Song of the Graduates (1852; MacDonald, no. 108). Although he received top marks for art and French, he had to leave West Point in 1854 for failing chemistry. He joined the drawing division of the US Coast and Geodetic Survey in Washington, DC, where he learnt to etch (e.g. the Coast Survey Plate, 1855; Kennedy, no. 1). In 1855 he left, took a studio in Washington and painted a portrait of his first patron, Thomas Winans (untraced; see Young and others, no. 3). He made his first lithograph, the Standard Bearer (Chicago, no. 2), with the help of Frank B. Mayer (1827–99) in Baltimore.

At 21 Whistler sailed for Europe, determined to make a career as an artist. He joined the Ecole Impériale et Spéciale de Dessin in Paris, where Degas was also a student, and in 1856 entered CHARLES GLEYRE’s studio. His copies in the Louvre included Ingres’s Roger Freeing Angelica (copy; U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.; Young, Macdonald, Spencer and Miles, no. 11). With HENRI MARTIN he saw Dutch etchings and Velázquez’s paintings at the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition in 1857. In Paris he met the English painters EDWARD JOHN POYNTER, T. R. Lamont (1826–98), GEORGE DU MAURIER and THOMAS ARMSTRONG, and in 1857 he asked them to etch illustrations to accompany his studio scene Au sixième (k 3) in an ultimately abortive joint venture known as ‘PLAWD’. Whistler was encouraged to etch from nature by Haden. In 1858, while touring the Rhineland with an artist–friend Ernest Delannoy, he etched five or six plates and traced others from sketches. Douze eaux-fortes d’après nature (known as the ‘French Set’) has seven Rhineland plates, dramatic compositions with finely modelled figures drawn with confident and varied line. Dedicated to Haden, 20 sets were printed in 1858 at Auguste Delâtre’s shop, and a further 50 sets were later printed in London. Also in 1858 Whistler met HENRI FANTIN-LATOUR and ALPHONSE LEGROS, who shared his interest in printmaking and respect for Courbet and Dutch 17th-century and Spanish art. Together they formed the informal Société des Trois. Whistler went with Fantin-Latour to the Café Molière and showed the ‘French Set’ to Courbet and Félix Bracquemond.

In November 1858 Whistler painted his first major oil, At the Piano (Cincinnati, OH, Taft Mus.; ymsm 24), which features Deborah Haden and her daughter. The predominantly sombre tonality and broad brushwork reflect his study of Courbet and Velázquez. The figures have a convincing solidity set against the rectangles formed by the dado and pictures on the wall behind—a formula Whistler often applied in later works. Rejected at the Salon in 1859, it hung with works by Legros and Fantin-Latour (with which it had obvious affinities) at FRANÇOIS BONVIN’s studio, where Courbet admired it.

(ii) 1859–66.

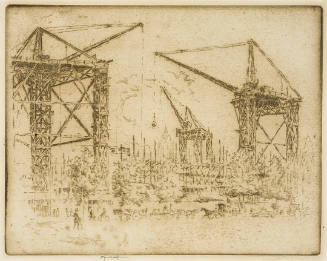

The failure of At the Piano in Paris and the favourable reception given the ‘French Set’ in Britain encouraged Whistler to move in 1859 to London, where he remained for most of his life. That same year he took rooms in Wapping on the River Thames and began the series of etchings known as the ‘Thames Set’ (Sixteen Etchings of the Thames). He completed most of the etchings that year, taking just three weeks to capture the fine detail of rickety warehouses and barges in Black Lion Wharf (k 42). The success of this series established Whistler’s reputation as an etcher.

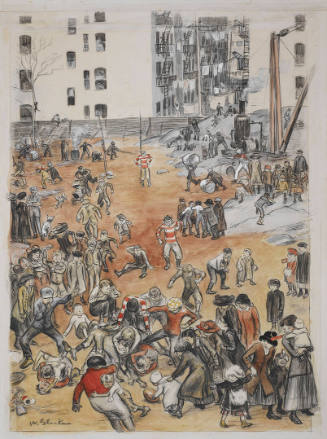

In 1860 At the Piano was accepted by the Royal Academy and bought by John Phillip. The Times critic wrote ‘it reminds me irresistibly of Velasquez’ (17 May 1860). The same year Whistler began to paint Wapping (Washington, DC, N.G.A.; y 35) from the balcony of The Angel, an inn at Cherry Gardens, Rotherhithe. He reworked the picture completely over four years: at first Joanna Heffernan, the coppery red-haired Irish model who became his mistress, was posed looking out over the Thames; later she was seated with two men at a table, a sailor from the Greaves boatyard and an old man, for whom Legros was later substituted. This colourful and atmospheric picture was bought by Winans and shown in New York in 1866 and at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867.

Joanna posed in Paris in December 1861 for Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl (Washington, DC, N.G.A.; y 38), the first of Whistler’s four Symphonies in White. It was rejected by the Royal Academy and hung at a small London gallery. Whistler claimed that the subject was not the heroine of Wilkie Collins’s novel The Woman in White, first published serially in 1859–60, ‘it simply represents a girl dressed in white standing in front of a white curtain’ (The Athenaeum, 5 July 1862). In 1863 it shared a succès de scandale with Edouard Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe at the Salon des Refusés. It was Paul Mantz, in the Gazette des Beaux Arts, who called it a ‘Symphonie du blanc’; he was the first to associate Whistler’s paintings with music. Later Whistler blamed Courbet for the painting’s realism, and between 1867 and 1872 he reworked it to make it more spiritual.

Whistler’s first contact with the Pre-Raphaelites was in 1862, when he met DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI and ALGERNON CHARLES SWINBURNE. In 1863 he moved to Chelsea, near Rossetti’s home and the boatyard of the Greaves family, two of whose members, Walter (1846–1930) and Henry (b 1843), became his followers. In 1863 he met the architect E. W. Godwin and went to Amsterdam with Haden to see Rembrandt’s prints. Neither Paris nor London suited Whistler’s health and he had to convalesce by the sea, where he painted his first great seascape, the Coast of Brittany (1861; Hartford, CT, Wadsworth Atheneum; ymsm 37), and the powerful Blue and Silver: Blue Wave, Biarritz (1862; Farmington, CT, Hill-Stead Mus.; ymsm 41). In 1865 he painted Courbet in Harmony in Blue and Silver: Trouville (Boston, MA, Isabella Stewart Gardner Mus.; ymsm 64). The two artists found much in common, including Jo, and Courbet painted her as La Belle Irlandaise (1865; New York, Met.; versions, Kansas City, MO, Nelson–Atkins Mus. A., priv. cols).

From 1863 Whistler began to introduce oriental blue-and-white porcelain, fans and other objets d’art from his own extensive collection into his paintings, signalling his increasing interest in Japonisme. Initially, these objects formed little more than props to what remained in both composition and finish essentially traditional Western genre subjects. Important examples include Purple and Rose: The Lange Leizen of the Six Marks (1863–4; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.; ymsm 47), which was given a specially designed frame with related oriental motifs, and La Princesse du pays de la porcelaine (1863–4; Washington, DC, Freer; ymsm 50). However, in February 1864 Whistler painted an oriental group, Variations in Flesh Colour and Green: The Balcony (Washington, DC, Freer; ymsm 56), which also incorporates compositional elements from the Japanese woodcuts of SUZUKI HARUNOBU and TORII KIYONAGA’s Autumn Moon on the Sumida. Although signed in 1865, it was reworked, even after exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1870. Whistler planned to enlarge it, but in his preliminary sketch, possibly started in 1867 (U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.; ymsm 57), the figures became more Greek than oriental, as his interests began to shift. He liked the collection of Tanagra statuettes owned by his Greek patrons, the Ionides family. In 1865 he had met ALBERT JOSEPH MOORE and both artists painted women in semi-Classical robes. By 1868 Whistler was at work on the ‘Six Projects’ (ymsm 82–7), decorative paintings of women with flowers, but, fearing that one of his studies, Symphony in Blue and Pink (Washington, DC, Freer; ymsm 86), was too similar to Moore’s work, he abandoned the project. He blamed Courbet for his failures and felt he lacked the basic draughtsmanship of an artist such as Ingres.

(iii) 1866–77.

During the mid-1860s Whistler went through a time of artistic and emotional crisis. He fell out with Legros, who was replaced by Moore in the Société des Trois, and he quarrelled finally with Haden in 1867. When his mother had moved in with him in late 1863, Jo had had to move out. To escape from family pressures, Whistler left for Valparaíso in 1866 to help the Chileans in a confrontation with Spain. He saw little fighting but painted his first night scenes, including Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Valparaíso Bay (Washington, DC, Freer; ymsm 76). On his return to London he left Jo, but she looked after his illegitimate son, Charles, born to the parlour-maid, Louisa Hanson, in 1870.

Without Jo, Whistler lacked a regular model, and in 1871, when another model fell ill, he asked his mother to pose. He struggled to perfect a simple composition with her sitting in profile before rectangular areas of dado, wall, curtain and picture, using thin broad brushstrokes for the wall, narrow expressive strokes for hands, flesh and curtain. The finished painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1872 as Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1: Portrait of the Artist’s Mother (Paris, Mus. d’Orsay; ymsm 101). Whistler wrote in The World on 22 May 1878, ‘To me it is interesting as a picture of my mother; but what can or ought the public to care about the identity of the portrait?’ He went on to explain, ‘As music is the poetry of sound, so is painting the poetry of sight, and subject matter has nothing to do with harmony of sound or colour.’

In 1869 Whistler started to paint the Liverpool ship-owner F. R. Leyland at Speke Hall, near Liverpool. The Arrangement in Black: Portrait of F. R. Leyland (1870–73; Washington, DC, Freer; ymsm 97) hung in Whistler’s first one-man exhibition at the Flemish Gallery, London, in 1874, which Rossetti, who introduced them, claimed had been financed by Leyland. A superb portrait of Leyland’s wife, Symphony in Flesh Colour and Pink (1871–3; New York, Frick; ymsm 106), was shown in the same exhibition. Whistler also made lovely drypoints (Kennedy, nos 109–10) and drawings of the Leyland daughters, Elinor and Florence (1873; U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.; see m nos 509–31), but did not finish their portraits. Pennell believed that the ‘Six Projects’ were intended for Leyland’s house at 49 Prince’s Gate, London. Leyland let Whistler paint the dining-room (designed by Thomas Jeckyll) to harmonize with La Princesse du pays de la porcelaine , which he had bought in 1872. Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room (Washington, DC, Freer; ymsm 178) became a major decorative scheme and one of the finest achievements of the Aesthetic Movement, but it so exceeded the original commission that artist and patron eventually fell out over the cost (see §2(v) below).

It was Leyland who in 1872 suggested that Whistler call his night pictures ‘Nocturnes’ (e.g. Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Old Battersea Bridge), c. 1872–5; London, Tate). At the Dudley Gallery Harmony in Blue-Green—Moonlight was bought in 1871 by the banker W. C. Alexander, but it was renamed Nocturne: Blue and Silver—Chelsea (London, Tate; ymsm 103). Alexander so liked the portrait of Whistler’s mother that in 1872 he ordered portraits of his daughters. Cicely suffered 70 sittings for Harmony in Grey and Green: Miss Cicely Alexander (ymsm 129. Thomas Carlyle was the subject of Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 2 (1872–3; Glasgow, City Mus. & A.G.; ymsm 137), which shares the severely restricted and sombre palette, solemn mood and economical composition of Whistler’s portrait of his mother. It was the first of Whistler’s oils to enter a British public collection, in 1891.

A red-headed English girl, Maud Franklin, took Jo’s place as Whistler’s mistress and principal model. Although she looks lovely in Arrangement in White and Black (c. 1876; Washington, DC, Freer; ymsm 185) and subtle in Arrangement in Black and Brown: The Fur Jacket (1876; Worcester, MA, A. Mus.; ymsm 181), she is depicted as a sombre figure in Arrangement in Yellow and Grey: Effie Deans (1876; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.; ymsm 183). Effie Deans, the heroine of Scott’s Heart of Midlothian, was an odd subject for Whistler, but perhaps appropriate because Maud, like Effie, bore an illegitimate child (by Whistler in 1878).

(iv) 1877–94.

By the late 1870s the artistic uncertainties of the 1860s had been resolved, but Whistler was in severe financial difficulties. In 1877 he sent Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1875; Detroit, MI, Inst. A.; ymsm 170), one of a series on Cremorne Gardens, to the first Grosvenor Gallery exhibition. JOHN RUSKIN wrote that he ‘never expected to hear a coxcomb ask 200 guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face’ (Fors Clavigera, 2 July 1877). Whistler sued him for libel. At the Old Bailey in November 1878, asked if he charged 200 guineas for two days’ work, Whistler said, ‘No, I ask it for the knowledge which I have gained in the work of a lifetime.’ He won damages of a farthing and faced huge costs. His account of the trial, Art and Art Critics, was published in December the same year.

On 8 May 1879 Whistler was declared bankrupt. He destroyed work to keep it from creditors, and the White House in Chelsea (destr.), which had been designed for him by E. W. GODWIN and completed only the previous year, had to be auctioned. In 1880 he left for Venice with a commission from the Fine Art Society for a set of 12 etchings. In fact he made 50 etchings, including Nocturnes (e.g. k 184; k 202, 213) and Doorways (k 188, 193, 196), of unsurpassed delicacy. He drew 100 pastels, including the glowing Venice: Sunset and Bead Stringers, with the figures set in a close hung with washing, brought alive by touches of colour (both Washington, DC, Freer; m 812, 788). His work made considerable impact on FRANK DUVENECK and his students, particularly Otto Bacher, who met him in Venice. The Fine Art Society showed the first 12 Etchings of Venice in December 1880. Whistler had to print 25 sets, but he kept trying to perfect them, and Frederick Goulding completed the editions after Whistler’s death. A second set, Twenty-six Etchings of Venice, exhibited in 1883 and published by Dowdeswell’s in 1887 in an edition of 30, was printed by Whistler with rare efficiency within a year.

The brewer Sir Henry Meux commissioned Whistler to paint two portraits of his wife: a luscious Arrangement in Black (1881–2; Honolulu, HI, Acad. A.; ymsm 228), delighted Degas at the Salon of 1882, while Harmony in Pink and Grey (1881–2; New York, Frick; ymsm 229) was exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery the same year. In 1883 Théodore Duret discussed with Whistler the problem of painting men in evening dress and posed, a domino over his arm to add a note of colour, for Arrangement en couleur chair et noir (New York, Met.; ymsm 252). To keep a unified surface, the whole canvas was repainted ten times before the Salon of 1885. Whistler sent work to the Impressionist exhibitions at the Galerie Georges Petit in 1883 and 1887 and to Les XX in Brussels in 1884. His own exhibition ‘Notes’—‘Harmonies’—‘Nocturnes’, including the painting The Angry Sea (Washington, DC, Freer; ymsm 282) and the watercolour Amsterdam in Winter (Washington, DC, Freer; m 877), hung at Dowdeswell’s in 1884. A second show in 1886 had pastels of models in iridescent robes and such watercolours as Gold and Grey—The Sunny Shower, Dordrecht (U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.; m 973).

On 20 February 1885 Whistler gave his ‘Ten o’clock lecture’. ‘Nature’, he said, ‘contains the elements, in colour and form, of all pictures, as the keyboard contains the notes of all music. But the artist is born to pick, and choose, and group with science, these elements, that the result may be beautiful.’ Whistler believed that art could not be made nor understood by the masses; a Rembrandt or a Velázquez was born, not made, and if no more masters arose, ‘the story of the beautiful is already complete—hewn in the marbles of the Parthenon—and broidered, with the birds, upon the fan of Hokusai—at the foot of Fusiyama.’

Whistler’s followers included WALTER RICHARD SICKERT and MORTIMER MENPES, who helped him print the Venice etchings, and in January 1884 they joined him at St Ives in Cornwall. In 1885 Whistler joined Sickert in Dieppe and went with William Merritt Chase to Antwerp, Haarlem and Amsterdam. In the same year he showed a portrait of the violinist Pablo de Sarasate (Pittsburgh, PA, Carnegie; ymsm 315) at the Society of British Artists, to which he had been elected the previous year. In 1886 he became President of the Society. He reorganized the exhibitions and brought in such young artists as Menpes, William Stott of Oldham (1857–1900), Waldo Story (1855–1915) as well as the Belgian ALFRED STEVENS as members and invited Monet to exhibit. When he was forced to resign in 1888 after objections to his exhibiting policy, his friends left too: ‘the “Artists” have come out, and the “British” remain’, he told the Pall Mall Gazette (11 June 1888).

Whistler started to paint Beatrice Godwin (1857–96), the wife of E. W. Godwin and daughter of the sculptor John Birnie Philip, in 1884: her portrait, Harmony in Red: Lamplight (U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.; ymsm 253), hung at the Society of British Artists exhibition of 1886–7. Beatrice and Maud Franklin both exhibited as Whistler’s pupils at the Society. They fought over Whistler and Maud lost. Beatrice’s husband died in 1886, and Whistler married her in August 1888. They had a working honeymoon in France, where he taught her to etch. In his ‘Renaissance Set’ he isolated architectural details, little figures and hens, in such etchings as Hôtel Lallement, Bruges (k 399), and painted such elegant watercolours as Green and Blue: The Fields, Loches (Ithaca, NY, Cornell U., Johnson Mus. A.; m 1183).

A set of six lithographs, Notes, was published by Boussod, Valadon & Cie. in 1887. With Beatrice’s encouragement, Whistler made lithographs, including stylish portraits of her sister Ethel. The Winged Hat and Gants de suède (c 34–5) appeared in the Whirlwind and Studio in 1890. Whistler hoped to popularize the medium but found the clientele limited. Experiments in Paris with colour lithography, as in Draped Figure, Reclining (c 56), were halted by problems with printers.

In 1889 Whistler made a set of ambitious etchings, including the Embroidered Curtain (k 410), in Amsterdam, which he felt combined ‘a minuteness of detail, always referred to with sadness by the critics who hark back to the Thames etchings, …with greater freedom and more beauty of execution than even the Venice set or the last Renaissance lot can pretend to’. Among the eager American purchasers of these etchings was Charles Lang Freer, who met Whistler in 1890 and amassed a huge collection of his work (now in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC). In 1891 Mallarmé led a successful campaign for the French State to acquire Whistler’s portrait of his mother. The following year Whistler drew for Vers et prose a sympathetic portrait of Mallarmé (c 60), who became one of his closest friends, and Whistler was himself drawn into the Symbolist circle. In 1892 the Whistlers moved to Paris.

Whistler remained a combative public figure. In June 1890 William Heinemann had published Whistler’s Gentle Art of Making Enemies—letters and pamphlets on art, designed by Whistler to the last jubilant butterfly. A second edition included the catalogue of his Goupil Gallery retrospective in 1892, Nocturnes, Marines & Chevalet Pieces, incorporating early reviews of his work. In 1894 George Du Maurier’s Trilby appeared in Harper’s with the character of ‘the Idle Apprentice’ based on the student Whistler, but he forced Du Maurier to make it less explicit. Sir William Eden commissioned a small full-length portrait of his wife in 1894 (U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.; ymsm 408). No price was set, and the amount and manner of payment upset Whistler. He kept the panel and changed the figure. Eden sued him, but Whistler won on appeal. Whistler later published his own account in Eden v. Whistler: The Baronet and the Butterfly (1899).

(v) Later life, 1894–1903.

In December 1894 Whistler’s wife became ill with cancer. They visited doctors in Paris and London and went in September 1895 to Lyme Regis in Dorset. Beatrice returned to London, but Whistler stayed to confront an artistic crisis, which echoed his emotional one. Samuel Govier posed for lithographs (e.g. The Blacksmith; c 127) and the masterly oil, the Master Smith of Lyme Regis (Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.; ymsm 450). Whistler felt he had fulfilled his Proposition No. 2: ‘A picture is finished when all trace of the means used to bring about the end has disappeared.’ Back in London, he held an exhibition of lithographs at the Fine Art Society. In 1896 he drew poignant portraits of his dying wife, By the Balcony and The Siesta (c 160, 159), and made his last nocturne, a superb lithotint, The Thames (c 161). Beatrice died on 10 May 1896.

The same year Whistler took a studio at 8 Fitzroy Street and in 1897 set up the Company of the Butterfly to sell his work, but it was not effective. In Paris his favourite model was Carmen Rossi (ymsm 505–7, c 71–4). Whistler helped her set up an art school (the Académie Carmen) in 1898, where he and the sculptor Frederick MacMonnies taught. Carl Frieseke (1874–1942) and GWEN JOHN were among the pupils, the most dutiful of whom, Inez Bate and Clifford Addams (1876–1932), became Whistler’s apprentices. The school closed in 1901.

In April 1898 Whistler was elected President of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers. Aided by Albert Ludovici jr (1852–1932), JOHN LAVERY and JOSEPH PENNELL, he supervised exhibitors and exhibitions, designing a monogram and catalogues. His friends Rodin and Monet sent work; other contributors included such Frenchmen as Toulouse-Lautrec, Bonnard, Vuillard and (under protest from Whistler) Cézanne; northern Europeans Gustav Klimt, Max Klinger, Max Liebermann, Jacob Maris, Franz von Stuck, Hans Thoma and Fritz Thaulow; and many Scots, led by George Henry, James Guthrie and E. A. Walton. The Society’s exhibitions were outstanding for their quality and unity.

In 1899 Whistler went to Italy and visited the Uffizi in Florence and the Vatican, where he liked Raphael’s Loggie but little else. He spent summers by the sea: at Pourville-sur-Mer in 1899 he painted panels of the sea (e.g. Green and Silver: The Great Sea), whose strength belies their size, and of shops, simple and geometrical (e.g. La Blanchisseuse, Dieppe; both U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.; ymsm 517, 527). In poor health, he spent the winter of 1900–01 in Algiers and Ajaccio, Corsica, painting, etching and filling sketchbooks with drawings of robed Arabs, donkeys and busy streets (U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.; m 1643). In October 1901 he sold his Paris house and studio and moved to Cheyne Walk, London. Freer took him on holiday in July 1902, but he fell ill at the Hôtel des Indes in The Hague. The Morning Post published an obituary, which revived him, and he went on to visit Scheveningen, the Mauritshuis and the galleries in Haarlem (see Morning Post, 6 Aug 1902).

Whistler was cared for after the death of his wife by her young sister, Rosalind Philip, who became his ward and executrix. After Whistler’s death in 1903, she bequeathed a large collection of his work to the University of Glasgow, including two introspective self-portraits (c. 1896; ymsm 460–61).

2. Working methods and technique.

Whistler’s oeuvre is considerable and of particular technical interest: about 550 oils, 1700 watercolours, pastels and drawings, over 450 etchings and 170 lithographs are known.

(i) Paintings.

Whistler’s early oil paintings vary in technique as he bowed to conflicting influences, Dutch art above all. Usually he painted thickly and broadly with brush and palette knife. His first over-emphatic use of colour soon modified, and he became sensitive to small variations in colour and tone. In the 1860s he used longer strokes, varying their shape and direction to describe details, with creamy ribbon-like strokes for draperies or water. In the 1870s his brushwork became bold, sweeping and expressive. He liked the texture of coarse canvas. The paint was thin and allowed to drip freely. Some of his Nocturnes, painted on a grey ground, have darkened badly. In the 1880s he began to work direct from nature, on panels only 125×200 mm. He painted freely, with creamy paint, making few alterations, whereas his later works were painted thinly, the brushwork softer and often showing signs of repeated reworking. His taste was refined and brushwork and colour schemes elegant. Not easily satisfied, he left many works incomplete and destroyed others.

Whistler perfected his use of watercolour when illustrating the catalogue of Sir Henry Thompson’s collection of Nanjing china in 1878 (see m 592–651. In the 1880s he worked on white paper laid down on card of the same size as his small panels of the period (see fig.). In the late 1880s he tried linen and in the late 1890s used brown paper. He painted thinly, leaving areas blank to suggest light or texture. He outlined a subject in pencil or brush, then added washes quickly with small brushes, altering, but rarely rubbing out.

(ii) Etchings and drypoints.

Whistler usually worked on the plate directly from nature, and he proofed and printed most plates himself. He brushed acid on the plate with a feather to get the strength of line required. He used various colours of ink, mainly black at first and brown later. In 1886 his first Proposition stated that etchings should be small because the needle was small; and no margin should be left outside the plate-mark. After 1880 he trimmed etchings to the plate-mark, leaving a tab for his butterfly signature. He liked Dutch paper, torn from old ledgers, and fine Japanese paper. Apart from published sets, most were printed in small editions.

In Whistler’s earliest etchings, influenced by Dutch art, intricately cross-hatched shadows blur outlines. The Thames etchings were drawn with a fine needle in fine detail, the foreground bolder, with lines scrawled across the plate. The plates were then bitten and altered little. The drypoints of the 1870s were drawn more freely, with longer lines and looser shading, giving silky, misty effects. They went through several states, because the lines wore down or because Whistler changed his mind, and were printed with a lustrous burr. The ‘Venice Sets’ were more elaborate. The design was drawn with short, delicate lines, etched quite deeply. Mistakes were burnished out and re-etched, and areas touched up with drypoint. In printing, a thin film of ink was smoothed across the plate to provide surface colour. Some plates went through a dozen states. The plates of the 1880s often had only a single state. They were smaller and simpler, with less surface tone, subjects vignetted and drawn with a minimum of short, expressive lines. Usually only one area was drawn in detail, shaded like velvet. The Dutch etchings of 1889 were larger and had many states. In the first he outlined the design, enriching it later with a variety of shading and cross-hatching softened with rubbing down, drypoint and some surface tone. His last etchings achieved amazing richness and variety in a single state, showing Whistler in total command of the medium.

(iii) Lithographs.

Whistler’s earliest lithographs and lithotints were drawn on stone and printed by Thomas Way & Son. Most later ones were drawn on transfer paper and transferred to stone and printed by Way’s firm. The transfer paper obtained from Way was mechanically grained, but later Whistler used a smooth paper, which he preferred. He sometimes worked on textured board or paper to add to the variety of line. The grain affected the appearance of the drawing and the success of the transfer. Whistler used the whole range of chalks in his first lithographs (e.g. The Toilet; c 10), hard and medium chalk, and some so soft it was applied with a stump of paper, and dark areas scraped down again. In the 1890s he usually drew with a hard crayon and used stumping for soft, velvety effects. For lithotints, Way mixed a wash to his own prescription, prepared stones for the artist and proofed and printed the result. Whistler made alterations in Way’s printing office. He experimented, but destroyed his failures. His first colour lithograph in 1890 (w 99) was to have had five colours, but two sheets did not transfer. Later experiments were more successful (w 100–01).

Whistler’s lithographs were published in small editions, of six plus two or three proofs in 1878, up to twenty-five by 1895. There were exceptions: Old Battersea Bridge (c 18), for instance, had over 100 pulled by 1896. Some drawings were transferred to several stones and printed in large numbers for journals, such as 3000 of The Doctor (c 110) for The Pageant in 1894. Whistler’s style was similar to that in chalk drawings of the same period, with firm, expressive lines, broken outlines and simple diagonal shading. He usually vignetted his subject and built up the details with flickering, curving lines, with cross-hatching enriching the shadows.

(iv) Pastels and other drawings.

Most of Whistler’s pastels were small (125×200 mm) and drawn on brown paper. The earliest, in black and white, were indecisive, a maze of circling lines. Around 1870 his line became more angular and economical. In Venice he gained confidence, outlining a view with lively and expressive strokes of black chalk and illuminating it with rich colours, shading or scumbling large areas for variety in texture. His later pastels were mostly of models, draped or nude, in his studio. Delicate and rainbow-coloured, his pastels became freer, more loosely drawn and increasingly expressive in his last years.

The early St Petersburg Sketchbook (U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.; m 7) includes careful drawings of figures, immature and weak in line. Whistler’s juvenile drawings were small vignettes, drawn jerkily with repeated angular, broken outlines, neatly cross-hatched and accented so that faces look like masks. His teenage drawings are a scrawl of zig-zag cross-hatching, with vague outlines. In his sketchbooks of 1858 (Washington, DC, Freer; see m 229–84), pencil studies from nature combine angular outlines and stylized shapes with softer, more varied shading. The few sketches surviving from the 1860s have simple shapes and curving outlines. Working drawings from the 1870s, mostly in pen, were straightforward. Shading replaced cross-hatchings. Caricatures were stylized, with jagged, pot-hooked lines. His sketchbooks were small (100×150 mm) and in constant use through the 1880s and 1890s (U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.; m 1101, 1144–5, 1333, 1363, 1475, 1580, 1634, 1643). Lively, broken lines, punctuated with dots, were used expressively. About 1900 his work became tentative, with silvery shading and very free, loose outlines.

(v) Designs and interior decoration.

Whistler designed floor-matting (Cambridge, MA, Fogg; Cambridge, Fitzwilliam; m 493–4), dresses for his sitters, such as Mrs Leyland (Washington, DC, Freer; see m 429–37), book covers for Elizabeth Robins and Charles Whibley (Washington, DC, Lib. Congr.; m 1479–81) and his own pamphlets and books (e.g. m 1238–70, 1547–79). He also designed furniture and painted Harmony in Yellow and Gold: The Butterfly Cabinet (U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.; ymsm 195), originally for a fireplace designed by E. W. Godwin for William Watts’s stand at the Exposition Universelle, Paris, in 1878. Whistler paid considerable attention to the framing of his own pictures, in the 1860s choosing chequered, basket-weave or bamboo patterns, and in the 1870s painting fish-scale patterns on the frame itself to accord with the tone or subject of his painting. In the 1880s he used a flat, beaded frame, in shades of gold to complement the picture. In the 1890s he developed a standard gilt frame with deep moulding and decorated with narrow beading for his paintings and pastels.

Whistler made gouache studies of colour schemes for interiors for W. C. Alexander (U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.; m 490), Ernest Brown of the Fine Art Society (Glasgow, U. Lib.; m 909), ships for the walls of his Lindsey Row houses (U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.; m 659) and others, but the schemes themselves have not survived. His major decorative projects were carried out for F. R. Leyland: besides the ‘Peacock Room’, he decorated the staircase at 49 Prince’s Gate (Washington, DC, Freer; ymsm 175). Although Whistler claimed he painted the ‘Peacock Room’ without a preliminary sketch, a large cartoon, pricked for transfer, for the panel of rich and poor peacocks at the south end of the room survives (U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.; m 584). Whistler, aided by the Greaves brothers, did the designs in gold leaf and painted in cream and verdigris blue over the ceiling, leather-covered walls, wood panelling and window shutters.

3. Personality and influence.

Whistler’s personality was central to his art and career. While in Paris, he read Henri Murger’s Scènes de la vie de bohème (1848) and was captivated by the bohemian world it portrayed, in which artists lived slightly apart from the rest of society and by a more relaxed moral code. In dress and manner Whistler presented the image of the immaculate dandy. In his work this attitude was reflected in a relentless perfectionism. He combined wit with a truculent aggressiveness towards critics and criticism. He shared with the other great dandy of the period, Oscar Wilde, a certain recklessness about the demands of money and social decorum. He survived bankruptcy in 1879 with dignity and became widely accepted in his later years as a great artist, but he remained by choice an outsider.

The ideas Whistler expounded so fluently have perhaps been as influential in the long term as his own work. He encouraged artists to recognize the pictorial possibilities of the urban landscape, notably the Thameside area of London, both in daylight and darkness. In this respect Sickert (his most important pupil) was his direct heir. Whistler’s emphasis on evocative colour and mood helped to undermine the position that literal naturalism had occupied as the dominant style in Victorian painting in Britain and the USA. In the USA Whistler was an important influence on such exponents of Tonalism as Thomas Wilmer Dewing and Dwight W. Tryon.

Through his own work and the exhibitions he organized, Whistler helped to introduce avant-garde artistic ideas from the Continent to Britain, where they were particularly well-received in Scotland. His technical mastery and imaginative exploration of etching did much to inspire the Etching Revival in Britain and France in the late 19th century and the early 20th, and his decorative work anticipated the achievements of Art Nouveau. [Margaret F. MacDonald. " Whistler, James McNeill." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 15, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T091375.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms