Jasper Johns

Jasper Johns

born 1930

American painter, sculptor, and printmaker. With ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG, he was one of the leading figures in the American POP ART movement, and he became particularly well known for his use of the imagery of targets, flags, maps, and other instantly recognizable subjects. Although he attended the University of South Carolina for over a year, and later briefly attended an art school in New York, Johns is considered a self-taught artist. His readings in psychology and philosophy, particularly the work of Wittgenstein; his study of Cézanne, Duchamp, Leonardo, Picasso, and other artists; and his love of poetry have all found expression in his work. His attention to history and his logical rigour led him to create a progressive body of work.

1. Early works, to c. 1960.

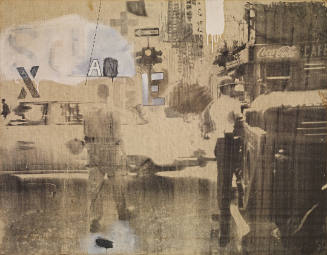

In 1954, after a dream, Johns painted a picture of the American flag (see fig.). At the time he was living in New York, as a struggling young artist. During the three years that followed, Johns painted more flags, as well as targets, alphabets, and other emblematic, impersonal images. None of this work was formally exhibited until 1957, when the Green Target (1955; New York, MOMA) was included in a group show at the Jewish Museum in New York. The dealer Leo Castelli gave Johns a one-man show at his gallery the following year. Johns’s paintings were sold to major private collectors, and three of his paintings were purchased by Alfred Barr for MOMA.

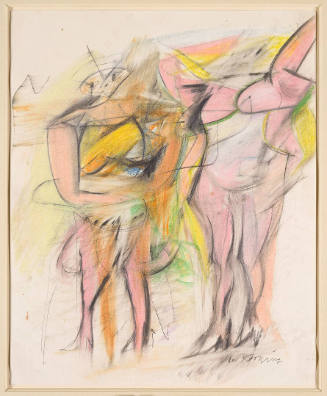

During most of this period Johns lived in the same building as Robert Rauschenberg. The two were close friends, saw each other’s work daily and had a considerable influence upon one another. Both Johns and Rauschenberg, in different ways, reintroduced figurative subject-matter to painting, and they are credited with inspiring the transition from Abstract Expressionism to Pop art. Target with Four Faces (1955; New York, MOMA) exemplifies many of the concerns of Johns’s earliest paintings. The target focuses attention on the theme of viewing: a target is something to see clearly, something to aim at, a visual display. Here the simple image is executed with deceptive complexity: the target itself in encaustic on collage, a difficult technique, which yields for Johns a rich, sensuous surface. Above the target are mounted four serial plaster casts of a single human face, while a hinged wooden lid offers the possibility of shutting away the disturbing faces. The painting provokes questions of perception, which many of Johns’s early paintings seemed to raise by their very existence.

Johns said that he chose to paint flat symbols such as flags (e.g. Flag, 1965; see COLOUR INTERACTION) and targets because he did not have to design them, because they were ‘things the mind already knows. That gave me room to work on other levels.’ The ambiguities and contradictions inherent in painting an abstraction with such a beautiful and painterly technique became the focus of critical comment. Although Johns had reintroduced the recognizable image to painting, he had done so in a paradoxical way.

Through Rauschenberg, Johns had met the composer JOHN CAGE in 1954. He met the artist Marcel Duchamp in 1959. Johns began his extensive reading of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in 1961. Through Cage, Johns met MERCE CUNNINGHAM and for many years worked with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company; he designed costumes, and on one occasion designed a set based on Duchamp’s Large Glass.

Johns had incorporated plaster casts in his earliest paintings, and in 1958 he began to make sculptures of everyday objects, such as lightbulbs and torches. Fashioned in actual size, these sculptures at first glance appeared to be castings, although they were not. The sculptures thus raised questions about what the artist had done, in a manner similar to the paintings of that period. The influential Painted Bronze (1960; Basle, Kstmus.), a sculpture of two Ballantine ale cans, was highly controversial at the time it was first shown. The ale cans were in fact fabricated in a complicated way: ‘Parts [of the sculpture] were done by casting, parts by building up from scratch, parts by moulding, breaking, and then restoring. I was deliberately making it difficult to tell how it was made.’ The artist’s humour was evident in such sculptures as The Critic Smiles (1959; artist’s col.), a toothbrush in which teeth are substituted for bristles. The piece also exemplifies Johns’s dictum that ‘You can see more than one thing at a time.’ In 1964 he painted According to What (priv. col., see 1977 exh. cat., pl. 115), a virtual catalogue of representational techniques that included casts of the human figure and imagery drawn from several of his earlier works. Throughout his career he was to execute these major works, which summarize his concerns and imagery at that time. This painting, in turn, led to a series of large-scale works of an increasingly abstract nature.

Johns made his first print in 1960, when Tatyana Grosman, founder of Universal Limited Art Editions, brought lithographic stones to his studio. In subsequent years, printmaking became an increasingly important part of the artist’s work. The imagery of Johns’s prints reflects that of his paintings, but the relationship between the two is not simple. ‘The paintings and the prints are two different situations’, he said in 1969. ‘Primarily, it’s the printmaking techniques that interest me … a means to experiment in the technique.’ He has also said, ‘I like to repeat an image in another medium to observe the play between the two: the image and the medium.’

2. The cross-hatching pictures.

In 1972 Untitled (Cologne, Mus. Ludwig), a difficult painting in four panels, introduced a new style: the cross-hatching pattern, which Johns employed in so many ways and with much vigour during the next decade. The mathematical precision underlying Johns’s cross-hatching pictures is exemplified by Scent (1973–4; Aachen, Neue Gal.). Here, three canvases painted in secondary colours are seen to exhibit a complex underlying order. First, one notices that no cross-hatched area in green, orange, or purple ever abuts an adjacent area of the same colour. Then too, the canvas panels differ in technique: one panel is painted on sized canvas, the second on unsized canvas, and the third in encaustic. Finally, each canvas is divided into three vertical panels, but only the centre panel is unique. Thus if the panels of the first canvas were labelled ABC, the second canvas would be CDE, and the third EFA. Most of Johns’s cross-hatching paintings carry a similar underlying idea about the mathematical manipulation of an image, or about the transition across the borders and junctions of the image. These paintings continue the concern with perception that marked Johns’s earliest work, while extending those concerns in a precise but apparently impersonal way.

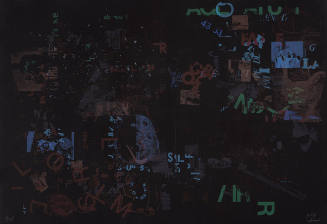

3. Works of the 1980s.

From the start of his career Johns always focused attention away from himself and onto the work. He emphasized the ready-made and impersonal elements of his creations: the pre-existing imagery, the stencilled lettering, the unmixed primary colours, things that were ‘not mine, but taken’. In interviews he explicitly denied that his work was to be seen as a reflection of himself or his feelings. In 1981 Johns began a period of more directly personal, self-referential work. Between the Clock and the Bed (1981; New York, MOMA) referred to a self-portrait by Edvard Munch of 1949 of the same name (Oslo, Munch-Mus.), yet Johns’s painting was entirely abstract. It suggested a self-portrait without making one explicitly. The paintings that followed, such as Perilous Night (1982; priv. col., see Francis, pl. 110) and Racing Thoughts (1983; New York, Whitney), were trompe l’oeil collages of distinctly personal reference. Racing Thoughts presents a view from the artist’s bath, complete with taps, wicker linen basket and a framed Barnett Newman print; but additional elements, such as an iron-on transfer Mona Lisa, a photo-puzzle of Leo Castelli, a skull with a Swiss avalanche warning sign, details from Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim altarpiece, pottery by the American ceramicist George Ohr (1857–1918), and a German porcelain vase with the profiles of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, are unquestionably personal to the artist.

In 1985–6 Johns executed four related paintings, The Seasons (see fig.), which again appeared to summarize concerns, techniques, and imagery. The paintings were begun when he moved into a new studio in French St Martin; they derive their initial inspiration from a painting of 1936 by Picasso, The Minotaur Moves his House, and very likely from the painting The Shadow (1953) as well. Each painting by Johns shows the artist’s shadow cast on a wall; the minotaur’s cart contributes the ladder and rope, as well as stars and the branch of a tree. These elements, ‘taken not mine’, are repeated and recombined in the four paintings, along with prior Johnsian imagery: the Mona Lisa, American flags, Ohr cups, and the ‘device circle’ swept out by a human hand and arm.

Johns soon ceased to be closely identified with Pop art, Minimalism, or any other movement. Independent and determinedly self-referential, he became closest in spirit to the tradition of the philosopher-painters such as Leonardo, Cézanne, and Duchamp, each of whom has been referred to directly in Johns’s own work.

Johns’s work always fetched high prices: in 1973 his Double White Map (1965) was auctioned for £240,000; in 1980 the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York paid £1 million for Three Flags (1958). In 1986 Out the Window (1959) was sold for £3.63 million to a private collector. In each instance the price set a record for work by a living American artist. [Michael Crichton. "Johns, Jasper." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 9, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T044999.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms