Roy Lichtenstein

Roy Lichtenstein

1923 - 1997

American painter, sculptor, printmaker, and decorative artist. His paintings based on the motifs and procedures of comic strips and advertisements made him one of the central figures of American POP ART.

He first studied under Reginald Marsh in a summer course at the Art Students League, New York, in 1939, continuing from 1940 to 1943 at Ohio State University in Columbus. He was particularly influenced by the teaching of Hoyt L. Sherman, a late Fauvist painter, designer, and architect who introduced his students to modernism in a period dominated by American Scene painting. Sherman was interested in the psychology of perception and problems of pictorial representation. In his teaching he insisted that the act of representation should be separated from everyday experience and considered solely for its formal qualities, as an ‘abstraction’.

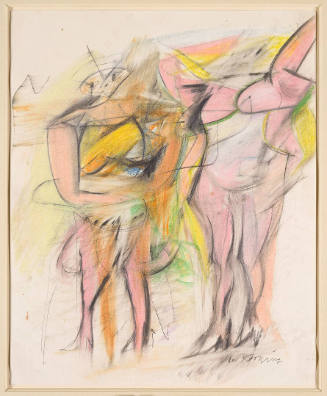

After military service in Europe in World War II Lichtenstein returned to Columbus in 1946, completing his Master of Fine Arts in 1949. The subject-matter of his early works became apparent c. 1949–50. Drawing on the biomorphic abstraction and heroic themes of Abstract Expressionism, Lichtenstein painted such subjects as anthropomorphic plants, beautiful women in gardens, and wild animals, as well as romantic medieval subjects of knights and battles. All this was painted with a subtle tongue-in-cheek irony, and stylistically oriented towards such European modernists as Picasso, Klee, Kandinsky, and Miró. In 1951 Lichtenstein devised his first major theme: American history and the conquest of the ‘Wild West’ as in Inside Fort Laramie (1955; priv. col., see Alloway, p. 14). He borrowed subjects treated by 19th-century artists, first using such well-known models as Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851; New York, Met.) and early paintings of Native American by artists such as Carl Wimar and Carl Bodmer, and then turning to anonymous illustrations. The source material on which he based his pictures was selected for its wealth of authentic detail and for its dependence on pictorial conventions; another critical factor was that he was working not from original works but from reproductions. He adopted a series of different artistic languages, first approximating Picasso’s style of the 1940s, in 1956 turning to a more ornamental idiom and then to Rococo motifs, and finally turning to abstraction in 1958 in a late variation of Action painting.

Lichtenstein taught from 1946 to 1951 at Ohio State University, then from 1957 at the State University of New York at Oswego, and from 1960 to 1963 at Douglass College, Rutgers University in New Brunswick, NJ, where he met Allan Kaprow and other artists associated with Happenings (see PERFORMANCE ART). These contacts encouraged his interest in cartoon imagery, stemming initially from small-scale 19th-century illustrations and from an anthropomorphic treatment of animals in the work of such modern artists as Miró. Lichtenstein recognized that devices favoured by cartoonists were very similar to those employed by such painters as Picasso and Klee, whom he had studied so intensively.

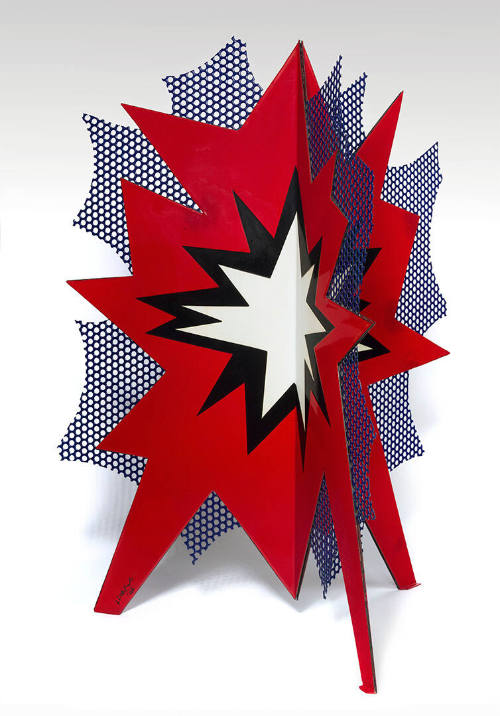

In 1961 Lichtenstein made the final break with his early work. Whereas he had previously translated his source materials into personal variants of Cubism or Constructivism, he now appropriated from comic strips not only the subject-matter but also the style. In these Pop paintings he favoured highly simplified colour schemes and procedures that mimicked commercial printing techniques, representing tonal variations with patterns of coloured circles that imitated the half-tone screens of Ben Day dots used in newspaper printing, and surrounding these with black outlines similar to those used to conceal imperfections in cheap newsprint. He applied these techniques to paintings based on small advertisements, as in Spray (1962; Stuttgart, Staatsgal.); war comics, for example Whaam! (1963; London, Tate) or As I Opened Fire (1964; Amsterdam, Stedel. Mus.); and comic strips on themes of love and romance, such as Hopeless (1963; Basle, Kstmus.), We Rose up Slowly (1964; Frankfurt am Main, Mus. Mod. Kst), and Drowning Girl (1966; New York, MOMA).

Having established this apparently anonymous style as, paradoxically, his personal style, Lichtenstein began to apply it also to paintings based on familiar works by other artists. Man with Folded Arms (1962; Milan, G. Panza di Biumo priv. col.) was based on a diagram found in a book on Cézanne’s composition, while Femme au chapeau (1962; Meriden, CT, B. Tremaine priv. col.) and Non-objective I (1964; Darmstadt, Hess. Landesmus.) were pastiches, rather than direct copies, after Picasso and Mondrian, respectively.

The essence of Lichtenstein’s procedure lay in the enlargement and unification of his source material, whether its original purpose was to tell a story or sell a consumer product, on the basis of strict artistic principles. This involved a strengthening of the formal aspects of the composition, a stylization of the motif and a ‘freezing’ of both emotion and action. At its most extreme, for example in Tension (1964; Paris, M. Boulois priv. col.), the process of formalization, combined with one’s awareness that the motif is only a segment of a larger narrative, transforms the image into a virtual abstraction. By such means Lichtenstein emphasized that comic strips and advertisements were not realist, as is often assumed, but highly artificial pictures that convey their messages with a sparing use of pictorial conventions. A constant if restrained irony and a gentle sense of humour contribute just as much to the cheerful lightness of Lichtenstein’s work as the balanced, completely harmonious composition.

By enlarging his source material, Lichtenstein emphasized the banality and emptiness of his motifs as an equivalent to the impersonal, mechanized style of drawing. This led to speculation as to his intended criticism of modern industrial America. The formalization and irony could be taken to support such a theory, but Lichtenstein ultimately would appear to accept the environment as revealed by his reference material as part of American capitalist industrial culture.

In 1962, the year in which he held his first one-man exhibition at the Leo Castelli gallery, New York, Lichtenstein made his first Pop prints, such as Foot and Hand (1962; see Waldman, 1969, p. 216), in which the association with comic books was strengthened by his choice of a technique generally used for commercial printing: offset lithography. In 1964 he made the first of his screen prints, Sandwich and Soda (see Waldman, 1969, p. 218), exploiting the inherent impersonality of the medium still further in works printed on synthetic materials, as in Seascape (1965; see Waldman, 1969, p. 222). The subtelty and technical inventiveness of his work as a printmaker, combined with his exquisite draughtsmanship, contributed greatly to his growing reputation.

The principle that Lichtenstein had created of basing each painting on a specific source was broken in 1964 with a series of imaginary landscapes. These were followed by paintings such as Yellow and Green Brushstrokes (1966; Darmstadt, Hess. Landesmus.), which parodied the broad brushwork of Abstract Expressionism in his usual comic-strip style. In such works Lichtenstein began to devise his own compositions, sometimes taking specific motifs from his own or other artists’ work as found objects or quotations. His pastiches of the brushstrokes of Action painting gave way in the later 1960s to paintings and sculptures based on the ‘rational’ geometry of Art Deco, such as the Modular series of canvases, and in the 1970s to parodies of such 20th-century styles as Cubism, Purism, Futurism, Surrealism, and Expressionism, always processed into the same dispassionate comic-strip style. Over the years his palette became richer and more varied, and in addition to the dots he incorporated other textures such as imitation wood-graining and cross-hatching.

Lichtenstein also periodically produced groups of sculptures. Some of the earliest of these were wood sculptures from pieces of furniture in the early 1950s; later followed glazed ceramics, including female busts such as Blonde (1965; Cologne, Mus. Ludwig) and a 1965 series, Ceramic Sculptures, which consisted of stacked cups and saucers (see 1977 exh. cat., pp. 7–26). These were followed by the Modern Sculpture series of 1967–8 (see Alloway, pp. 58–9), which made reference to motifs from Art Deco architecture. In his painted bronzes of the mid-1970s (see Cowart, pp. 149–59) Lichtenstein made punning use of linear devices from his paintings to produce three-dimensional but flat-looking representations of familiar objects. In the late 1970s and during the 1980s, Lichtenstein received major commissions for works in public places: the sculptures Mermaid (6.4×7.2×3.4 m, 1979; Miami Beach, FL, Theat. Perf. A.) and Brushstrokes in Flight (1984; Columbus, OH, Port Columbus Int. Airport), and the five-storey high Mural with Blue Brushstrokes (1986; New York, Equitable Cent.).

The theme basic to all of Lichtenstein’s work was succinctly stated in his Mirrors series of 1970–72, such as the oval Mirror No. 2 (Philadelphia, PA, Kardon priv. col., see Alloway, p. 67), which explicitly questioned the assumption that the function of representational art was to reflect reality. Throughout his work in all media, he continued to affirm that the arrangement of forms and colours obeyed pictorial rules independent of the subject portrayed. The succession of styles alluded to in his art, rather than being taken for granted as a self-perpetuating system, thus becomes an instrument for understanding art as the expression of an ideal state. [Ernst A. Busche. "Lichtenstein, Roy." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 9, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T050915.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms

French, 1864 - 1901