Diego Rivera

Diego Rivera

Mexican, 1886 - 1957

Mexican painter and draughtsman. He was one of the most important figures in the Mexican mural movement and won international acclaim for his vast public wall paintings, in which he created a new iconography based on socialist ideas and exalted the indigenous and popular heritage in Mexican culture. He also executed large quantities of easel paintings and graphic work.

1. Life and work.

Rivera’s artistic precocity was recognized by his parents, both of whom were teachers. He was drawing at two, taking art courses at nine and enrolled at the Academia de S Carlos in Mexico City at eleven. There the quality of his work, especially his landscape painting, earned him a scholarship at fifteen and a government pension at eighteen. At nineteen he was awarded a travel grant to Europe, and in 1907 he went to Spain, settling in Paris two years later. In November 1910 he returned to Mexico for an exhibition of his work at the Academia, which was part of the Mexican Centennial of Independence celebrations. The Mexican Revolution began the day the exhibition opened, and Rivera returned to Paris early in 1911, remaining there until 1919.

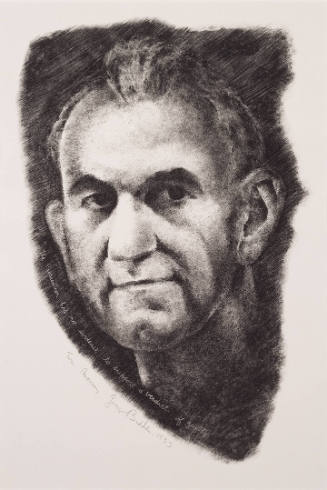

Rivera developed into an accomplished painter during his years in Paris, dextrously exploring both traditional and avant-garde styles. Works such as the Old Ones (1912; Mexico City, Dolores Olmedo priv. col., see 1986–8 exh. cat., p. 36) reflect the influence of El Greco and Rivera’s contact with Spanish modernist circles, while his portrait of the Mexican painter Adolfo Best Maugard (1913; Mexico City, Mus. N.A.) displays the direct influence of Robert Delaunay’s Orphism. Two Women (1914; Little Rock, AR A. Cent.) shows Rivera’s mastery of the Analytical Cubism of Albert Gleizes, and the Zapatista Landscape (The Guerrilla) (1915; Mexico City, Mus. N.A.) echoes the Synthetic Cubism of Picasso and Juan Gris. Rivera made numerous exploratory drawings for these and other paintings. During his later years in Paris he drew a series of pencil portraits in the style of Ingres, of which the finest are the portrait of Angeline Beloff (1917; New York, MOMA), his mistress for most of his European stay, and the portrait of Jean Cocteau (1918; Austin, U. TX, Ransom Humanities Res. Cent.). By 1917 Rivera had met the art historian Elie Faure, who directed his interest away from the extremes of modernism towards early Italian Renaissance painting. He also stimulated Rivera’s interest in the work of Cézanne, whose influence can be seen in the composition and brushwork of his portrait of Elie Faure (1918; Paris, priv. col., see Wolfe, pl. 43).

By 1918 Rivera was becoming increasingly pressed by both personal and political matters. His relationship with Angeline Beloff was foundering, and their son died of influenza. In 1919 his daughter Marika was born of a liaison with Marevna Vorobyov-Stebelska. At the same time, he was being urged to return to Mexico to participate through his work in the Revolution. David Alfaro Siqueiros visited him in 1919 in connection with this, and both he and Faure discussed the role of the mural as a proletarian art form. In 1920 José Vasconcelos, later Secretary of Education under President Obregón (1921–4), urged Rivera to go to Italy to study Renaissance murals. Rivera spent over a year there, studying some of the greatest wall paintings in Italy.

Rivera returned to Mexico in 1921 just as Vasconcelos was beginning to consolidate his programme of mural painting in Mexico City (see MEXICO, §IV, 2(IV)(A)). He began an intensive study of indigenous art and folk culture in Mexico, travelling to the Yucatán late in the year and to Tehuantepec the next. He later became an avid collector of Pre-Columbian and folk art and made use of their motifs in his murals. In 1922 he began his first government-sponsored mural, the Creation, in the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria in Mexico City. By this time a large number of artists had been assembled by Vasconcelos to paint murals, and in the autumn, led by Siqueiros, they formed the Sindicato de Obreros Técnicos, Pintores y Escultores. Rivera also joined the Mexican Communist Party, with which he had a stormy relationship for the rest of his life. In 1922 he married Guadalupe Marín, by whom he had two daughters.

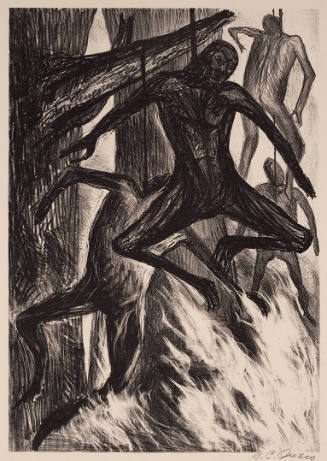

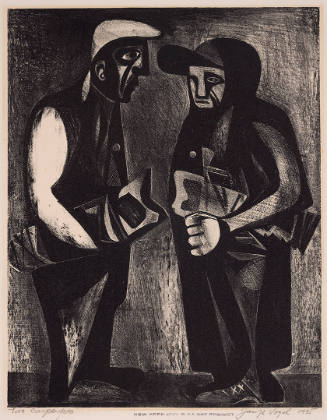

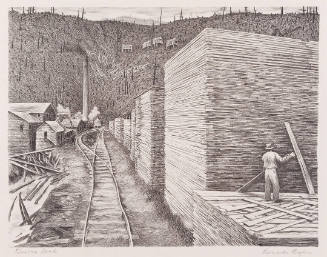

Over the next 15 years Rivera painted a large number of murals. In 1923 he began work with a team of artists on the walls of the two three-storey patios of the new Secretariat of Education building in Mexico City. He soon assumed sole responsibility for the entire project, creating over a hundred fresco panels by 1928, covering over 1585 sq. m. Of these, The Mine and Embrace and Peasants (both 1923), in the Court of Labour, combine the stylistic influence of Giotto with Mexican folk themes, while one of the last, the Distributing Arms panel (1928), which displays all the characteristics of his mature mural style, introduces the great series known as the Corrida [or Ballad] of the Proletarian Revolution, on the third storey of the buildings surrounding the Court of Fiestas. Late in 1924 Rivera also undertook a series of murals in the administration building and in the laicized chapel of the Escuela Nacional de Agricultura (now the Universidad Autónoma) at Chapingo in the state of Mexico, which he completed in 1927. That year his marriage to Guadalupe Marín collapsed after the birth of their second daughter. In the autumn he travelled to the Soviet Union, staying there until May 1928 when he returned to Mexico and completed his Secretariat murals.

There were numerous changes in Rivera’s life during 1929. He became Director of the Academia de S Carlos and began the History of Mexico mural on the main stairway of the Palacio Nacional in Mexico City. In August he married the artist Frida Kahlo, with whom he had a tempestuous relationship until her death in 1954. The Communist Party was outlawed in Mexico in 1929, and he was expelled from it because of Trotskyite sympathies. The US ambassador Dwight D. Morrow commissioned him to paint a mural on the History of Cuernavaca and Morelos at the palace of Cortés in Cuernavaca, Morelos, which he finished late in 1930. By this time he had been forced to resign as director of the Academia by the right-wing Calles government, and he accepted an invitation to paint a mural in San Francisco, CA, which provided an opportunity to escape a difficult situation.

Between 1930 and 1934 Rivera painted five murals in the USA. The first two were his Allegory of California for the Luncheon Club of the Pacific Stock Exchange in San Francisco and the Making of a Fresco, Showing the Building of a City in the San Francisco Art Institute, both painted in 1931. His Detroit Industry frescoes in the garden court of the Detroit Institute of Arts, painted in 1932–3, constitute his most important mural cycle outside Mexico . In 1933 he began Man at the Crossroads for the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) building in the Rockefeller Center, New York. He was prevented from finishing the mural because it contained a portrait of Lenin, and it was destroyed early the next year. Having been deprived of several anticipated commissions by this scandal, Rivera painted a series of 21 overtly political panels called Portrait of America for the anti-Stalinist New Workers School in New York. Only eight panels survive in various locations (see 1986–8 exh. cat., p. 301).

Returning to Mexico City, Rivera painted a revised version of his RCA mural, entitled Man, Controller of the Universe (1934), in the Palacio de Bellas Artes. In 1935 he completed his murals on the stairs of the Palacio Nacional (for example see [not available online]), and the following year he painted a series of four panels for the Hotel Reforma in Mexico City entitled Burlesque of Mexican Folklore and Politics (Mexico City, Pal. B.A.). From 1937 to 1942 he received no mural commissions in Mexico and devoted himself mainly to easel painting and portraiture. During this period he was host to the exiled Leon Trotsky, who stayed for some time with Rivera and Frida Kahlo at their home in Coyoacán, Mexico City. In 1940 he painted a huge mural on the theme of Pan-American Unity for the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco (6.71×21.3 m; San Francisco, CA, City Coll.).

In 1942 Rivera began the construction of the pyramid-shaped ‘Anahuacalli’ near Coyoacán, as a residence and private museum for his collection of Pre-Columbian art. He was involved with this structure, which became known as his ‘pyramid’, for the rest of his life. In his last years he created a number of murals in Mexico City for public and private buildings. Of these the most notable are the series of frescoes entitled From the Pre-Hispanic Civilization to the Conquest (1945–51), painted on the walls of the colonnade that surrounds the main courtyard of the Palacio Nacional, and his Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Park (1947–8) for the Hotel del Prado. In 1953 he designed his last mural, the mosaic Popular History of Mexico, for the façade of the Teatro de los Insurgentes, Mexico City. After the death of Frida Kahlo he married his dealer, Emma Hurtado, in 1955 and travelled to Moscow that year for the treatment of cancer, which proved ineffective.

Although Rivera’s fame stemmed from his murals, much of his wealth was generated by his portraiture, particularly after the late 1930s when his mural commissions temporarily ceased. Many of his portraits were of female celebrities or wealthy society women, for instance Adalgisa Nery (1945; R. & D. Mareyna priv. col., see 1986–8 exh. cat., p. 201). The gestures and facial features of the sitters are often exaggerated, both in these highly stylized portraits and in Rivera’s many depictions of Mexican children dating from the same period, for example Irene Estrella (1946; Exeter, NH, Lamont Gal.). In the 1940s Rivera also painted several easel works with Surrealist overtones, possibly due to the influence of Frida Kahlo, for instance Symbolic Landscape (1940; San Francisco, CA, MOMA). The painting depicts twisted and distorted tree forms and was exhibited in the Exposición Internacional del Surrealismo held at the Galería de Arte Mexicano in Mexico City in 1940.

2. Style and iconography.

One of Rivera’s most complex and successful mural cycles was painted in the former Jesuit chapel in Chapingo, which served as the auditorium of the Escuela Nacional de Agricultura (now the Universidad Autónoma). The artist devised a programme of 41 fresco panels in which socialist revolution parallels the evolution of nature. The two themes mirror each other along the opposite walls of the chapel, and the images use symbolism drawn from Christian and Aztec cultures, allegorical female figures derived from academic art and modernist montage techniques. If one examines only the principal panels, the programme painted along the southern, windowed, wall begins in the narthex with a depiction of the Blood of the Revolutionary Martyrs Fertilizing the Earth. Proceeding eastward down the nave are four allegorical scenes, Subterranean Forces, Germination, Maturation and The Abundant Earth, tracing the development of natural growth from seed to flowering plant. Along the opposite wall and corresponding conceptually to these five panels are the Birth of Class Consciousness in the narthex, Formation of Revolutionary Leadership, Underground Organization of the Agrarian Movement, Continuous Renewal of Class Struggle and the Triumph of the Revolution. The two series culminate in the image painted on the eastern wall, depicting the Liberated Earth and Natural Forces Controlled by Man. The scene is centred around the huge figure of a reclining female nude, representing the fertile earth, and the circular shape formed by a windmill’s blades, which is open to interpretations as wide-ranging as a Christian monstrance and the ceremonial Aztec calendar stone.

This imposing east wall at Chapingo is also typical of Rivera’s mature style. It had worldwide influence on public mural painting and especially on artists employed by the New Deal’s Treasury Department and WPA art programmes during the 1930s in the USA. A number of traits characteristic of this style can be seen in the Liberated Earth. A Cubist compositional structure suspends the pictorial complex between a clearly defined foreground and a background formed by a continuous sky. The sky also forms the background of the ceiling panels, in which male figures holding revolutionary symbols are depicted from below. Through the sky, the ceiling panels and the image on the east wall become united within the architectural frame, which Rivera always respected. The wall plane is maintained in the Liberated Earth by the use of a relatively high horizon. The unification of that wall plane is achieved by means of a geometric system loosely based on the golden section; at Chapingo this can be seen in the main panel in the proportionate square and rectangle delimited by the windmill and extended above by the woman’s gesture. The geometrical grid is countered by movement within it, as in this image by the gestures of the various figures. Rivera used simple, bold modelling in his murals, derived from the example of Giotto’s frescoes and from the demands of mural scale and the fresco technique. The murals show a basic palette of earth colours and black, set off with carefully placed bright colours. Figures are placed one behind the other on a series of overlapping planes that recede from the front to the back of the composition, and heads are massed in a similar arrangement, best seen in the nave panels at Chapingo. At least one deep recessional space is usually incorporated into Rivera’s mature murals; on the east wall at Chapingo, for example, this consists of the central cultivated field. Rivera frequently attempted to relate the content of his murals to the external world by some system of symbolism based on the physical orientation of the murals; at Chapingo this was achieved by painting corresponding panels along the opposite walls of the nave and by using the east wall as the source of generative light.

Although Rivera created a vast number of easel works, drawings and prints, which made his fortune as his fame increased, his renown was based on his murals. These displayed a sensibility that was radically different from that of his colleagues in the Mexican mural movement, for he possessed none of Orozco’s introversion and lacked Siqueiros’s political passion. He was an extrovert with a prodigious facility for painting that stemmed not only from his cosmopolitan training but also from his intellectual openness to mathematics and science as well as the humanities. He was also capable of conceiving art in the context of its historical potential, rather than as a purely personal statement or as a political weapon. Whereas his two colleagues had immediate experience of the human cost of the Revolution, Rivera never experienced the fighting directly, returning to Mexico only when the conflict had abated. For Rivera, injustice was abstract, not concrete; he was therefore not as extreme in his politics and personal opinions as were his colleagues. Although he had a lifelong sympathy with Marxist ideals, he was not psychologically committed to the Communist Party’s shifting line, especially when it interfered with art. This led to his exploitation by capitalist interests during the early 1930s. Rivera’s art, however, transcends such issues, through his remarkable idiosyncratic fusion of Renaissance, academic, modernist and indigenous Mexican techniques, styles and motifs, and his creation from them of a humanistically and aesthetically responsible socialist iconography. [Francis V. O’Connor. "Rivera, Diego." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 10, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T072302.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms