Willem de Kooning

Willem de Kooning

1904 - 1997

Painter and sculptor of Dutch birth. De Kooning was a leading figure of ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM whose painterly gesturalism transcended the conventional definitions of figuration and abstraction and substantially influenced art after World War II.

1. Early work, to c. 1945.

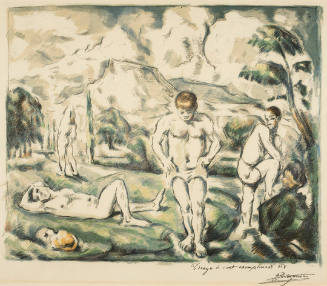

De Kooning’s artistic talent was recognized at an early stage, and from 1916 to 1924 he attended the Academie van Beeldende Kunsten in Rotterdam while working at a commercial art and decorating firm. His earliest-known works, of which few survive, reflect his academic training and the influence of Old Masters, for example Still-life: Bowl, Pitcher and Jug (c. 1921; New York, Met.). In 1926 he emigrated to the USA, moving in 1927 to New York, where he continued to make a living as a commercial artist. Soon he became involved with the New York avant-garde, in particular with John Graham, Arshile Gorky and Stuart Davis. Their influence and that of Miró, Arp, Picasso and Mondrian is apparent in de Kooning’s abstract still-lifes of the 1930s and early 1940s, compositions of biomorphic and geometric shapes and lines in high-key colours, integrated into an architectonic structure. He employed similar techniques while working in 1935–6 for the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration on various mural projects, none of which was executed. The increasingly simple and flat poetic abstractions exercised the metamorphosis of perceived reality into ambiguous abstract images, an elemental technique employed throughout his career.

De Kooning’s work is characterized by an inherent stylelessness, resulting from the constant parallel exploration of divergent themes and techniques. In the 1930s he worked simultaneously on abstractions and a series of male figures. The generally unfinished paintings combine classically inspired anatomy (influenced particularly by Ingres’s work) with the formal fragmentation of Cubism, as in Seated Figure (Classic Male) (c. 1940; U. Houston, TX, Sarah Campbell Blaffer Gal.). The silent appeal of the solitary figures, positioned in vague and indefinite surroundings, reflected the uncertainty and isolation of the Depression era, for example in Working Man (drawing, c. 1938; Max Margulis priv. col., see Hess, 1972).

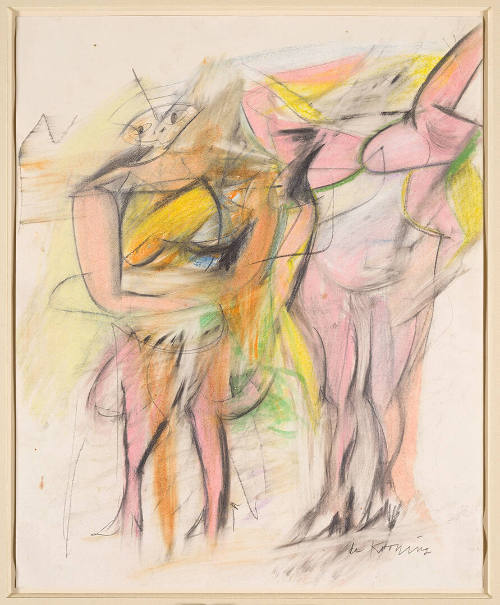

In 1938, after meeting his future wife, the American painter Elaine Fried, de Kooning began his first series of Women, the central theme in his work. The images of women of the late 1930s and early 1940s, in increasingly bright colours and violent contrasts, possess a powerful and erotic immediacy, as in Seated Woman (c. 1940; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.) and Woman (1944; New York, Met.). The figures are progressively fragmented into irregular planar shapes and contrasted with geometric backgrounds. De Kooning named the anonymous and indefinite backgrounds ‘no-environments’, leaving the possibility for a multiplicity of places and situations. Pink Angels (c. 1945; Los Angeles, CA, Frederick Weisman Co.) is the climax of the first Women series, transgressing the static frontality of the earlier figure paintings and indulging in a dynamic frenzy, barely controlled by the receding geometric structure of the background. De Kooning’s attempt to overcome the restrictions of rational control, inspired by Surrealist automatism, is reflected in their strong graphic quality and unfinished state.

2. Mature work, c. 1945 and after.

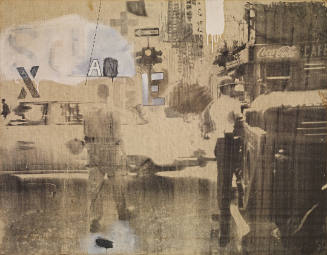

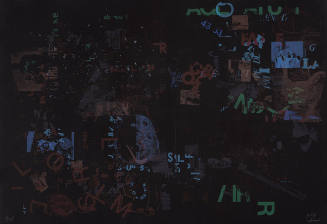

The reduction of de Kooning’s palette and the close-textured composition of irregular shapes in the Black-and-white Abstractions (1945–50; see fig.) balanced the figure–ground relationship and created a dense, shallow space, as previously suggested in Pink Angels. Random fragments of memory are evoked by letters and figures in some of the Black-and-white Abstractions, evidence of de Kooning’s early training as a sign-painter (e.g. Zurich, 1947; Joseph H. Hirshhorn estate, see 1983 exh. cat., New York, pl. 161). Excavation (2.03×2.54 m, 1950; Chicago, IL, A. Inst.) is the violent and shocking climax of the Black-and-white paintings and de Kooning’s largest painting up to that time. The primarily white canvas with black contours and glimpses of red, yellow and blue bursts with a complex network of superimposed and interlocked shapes, reminiscent of human limbs. The composition moves around an obvious focal point, despite its all-over fragmentation, consuming everything in an apocalyptic vortex. Excavation highlights de Kooning’s continuous balancing act between representation and abstraction, hardly ever succumbing to complete non-objectivity. ‘Even abstract shapes must have a likeness’, as de Kooning stated (see 1968 exh. cat., p. 47).

From 1950 to 1955 de Kooning worked on a second series of Women, rejecting the then dominant stylistic canon of abstraction: ‘It’s really absurd to make an image, like a human image…But then all of a sudden it becomes even more absurd not to do it’ (see Sylvester, p. 57). He had, however, never completely abandoned figurative work, and his suite of fragmented Women between 1947 and 1949, such as Woman (1948; Washington, DC, Hirshhorn), forecasted the challenge to established notions of femininity. For two years he worked on the momentous Woman I (1950–52; New York, MOMA), ‘an image which has become a totem and icon of the times’ (see 1968 exh. cat., p. 12). The genesis of Woman I is documented in Rudolph Burckhardt’s celebrated photographs, illustrating the innumerable revisions and cinematographic process of creation in the quest for a true, yet subconscious image (see Waldman, pp. 88–9). De Kooning perpetually referred to drawings, attaching many of them to the canvas and subsequently overpainting them. Drawing was always an important and integral part in the evolution of his pictorial solutions. In the place of her mouth he fixed a cut-out of a female smile from a magazine advertisement, as a point of orientation and as epigrammatic reference to the ubiquitous American idols of femininity. De Kooning was always a very eclectic artist, and the Women were also inspired by classical formulations by Rubens, Rembrandt, Matisse and Picasso. Gradually the woman’s clearly defined surrounding was transformed into his typical ‘no-environment’, with its implications of vagueness and insecurity, emphasizing the blank stare, the frozen grin and the overwhelming presence of the monstrous figure with its large breasts. When Woman I was exhibited in 1953 in New York at the Sidney Janis Gallery with five other Women paintings, it shocked the public and critics. Images of the bulky women, with their frontal immediacy and destructive fragmentation into gestural brushstrokes, were attacked as violent, ferocious and sexist. De Kooning’s detractors failed to recognize that the amalgam of stereotypes was an ironic comment on the obsession with the banal and artificial world of film, television and advertising. It is this iconoclastic quality and diversity of references condensed into a single image that makes Woman I such a controversial and successful painting.

De Kooning liberated himself from the power of the Women through their gradual transformation into landscapes, as in Woman as Landscape (1955; Janet and Robert Kardon priv. col., see Waldman, p. 103), which led to the Abstract Urban Landscapes, (1955–8) and Abstract Parkway Landscapes (1957–61). From 1955 the female figure was slowly absorbed by its environment, creating hybrid images that defy conventional genre categorizations, as de Kooning intimated in his remark, ‘The landscape is in the Woman and there is Woman in the landscape’ (see 1968 exh. cat., p. 100). The messy and elaborate all-over surfaces of the Abstract Urban Landscapes, such as Gotham News (c. 1955; Buffalo, NY, Albright–Knox A.G.), record the chaos of New York, the cacophony of its events, sounds, smells and visual impressions. A more poetic mood emanates from the broad and dramatic brushstrokes of the Abstract Parkway Landscapes, extending over the whole width of the canvas and conveying ‘sensations of the feeling of going to the city or coming from it’ (see Sylvester, p. 57). A sweeping painterliness is achieved in the Abstract Pastoral Landscapes (1960–63) with lush and sensual splashes of white, pink and yellow paint capturing the atmosphere at Long Island, NY, of brilliant light, sea and nature, as in Door to the River (1960; New York, Whitney). Like Franz Kline’s bold calligraphic paintings, de Kooning’s Abstract Landscapes seem to represent only an enlarged detail of a larger scene, thereby avoiding traditionally composed European images. He achieved a virtuosity of touch, quickness and security of execution that was unusual in artists of his generation but akin to the technique of Old Masters.

The thematic centrality of the Women and the Abstract Landscapes continued throughout the 1960s, as de Kooning produced ever more novel formulations of his basic themes, contradicting premature proclamations of the decline of his creative powers. Though his brushwork and colours softened, the Women of the 1960s are more vivid, physical and erotic than ever. Woman, Sag Harbour (1964; Washington, DC, Hirshhorn) appears frontally in sensuous fleshlike colours, her extremities spread out in a provocative and overtly sexual pose. The late 1960s and early 1970s witnessed a revival of the ‘Woman in Landscape’ theme, celebrating the idyllic harmony of human figure and nature in such works as Woman in Landscape III (1968; priv. col., see 1983 exh. cat., New York, pl. 229).

De Kooning’s versatility was exemplified by his venture into sculpture, a medium completely new to him (1969–74). In his sculptures he translated the physicality of the painted figure into three dimensions without compromising their vitality and energy. The twisted and distorted figures reveal the traces of their creation, products of the direct contact with the hands of the sculptor, as in Seated Woman on a Bench (1972; Amsterdam, Stedel. Mus.). As with his paintings and drawings the closed form is destroyed and the sculptures reach out and respond to their environment, extending a process initiated by Auguste Rodin, Matisse and Alberto Giacometti. Aesthetic autonomy is manifest in de Kooning’s constant oscillation between abstraction and representation, figurative and landscape painting, that continued in the 1970s with a smooth transition from the ‘Women in Landscape’ to a series of Untitled works (1975–9; see Untitled XIX, 1977). The atmosphere of his environment in East Hampton, NY, is reflected in an impasto of short and hectic brushstrokes with enigmatic appearances of the human figure, as in Untitled V (1977; Buffalo, NY, Albright–Knox A.G.). An increasingly lyrical quality began to infuse his work in the early 1980s. In 1982 he reduced broad shapes to an intricate web of arabesque lines on a transparent white ground. The intense luminosity of colours and weightlessness of floating curves correspond to the calm movement of the sea and its interplay of water and light, in works such as Untitled XVII (1982; New York, Xavier Fourcade).

Willem de Kooning: Untitled, 1950 (Private collection); © 2010 The…The central issue in de Kooning’s art was his creative use of ambiguity, achieved through disorientation and fragmentation, manipulation of perspective, mutilation, dissolution and a reassemblage of figures and objects. For de Kooning the process of painting and drawing was a way of experiencing, recording and appropriating reality, ideas and subjects emerging in the process of creation through free association. The variety and constant transformation of basic themes reflected his view of the world as a sum of indefinite and ever-changing possibilities. The ambiguity that reigns in the formal structure of the paintings continues on a semantic level, evoking a multiplicity of meanings and moods: joy, lust and effusiveness to some; brutality, drama and violence to others. De Kooning maintained deliberate stylistic contradictions and a strong element of uncertainty, open for developments in any direction.

3. Influence.

From the 1950s de Kooning’s fame and success spread, making him one of the most influential artists of the period. While a number of serious followers, such as the American painters Michael Goldberg (1924–2007), ALFRED LESLIE, GRACE HARTIGAN and JOAN MITCHELL, developed de Kooning’s example into an individual pictorial mode, many others were deceived by his seemingly easy-to-imitate style. The attempt to liberate themselves from the powerful example of de Kooning, the archetypal gestural painter, led to an ironic appropriation by Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and Pop artists. A revival of interest in his work came with the renaissance of figurative and Neo-expressive painting in the early 1980s. [Christoph Grunenberg, et al. "De Kooning." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 8, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T021873pg1.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms

French, 1864 - 1901