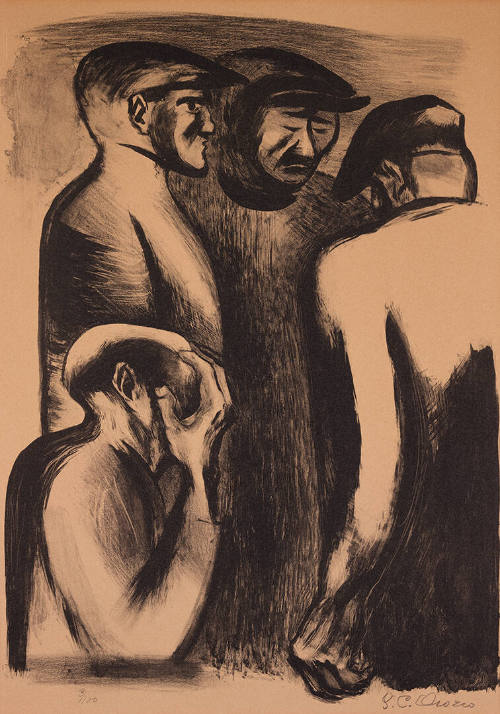

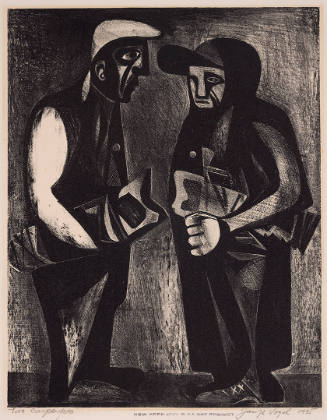

José Clemente Orozco

José Clemente Orozco

Mexican, 1883 - 1949

Mexican painter and draughtsman. He was one of the three most important Mexican mural painters, and his expressionist style has been particularly influential among younger generations of international mural artists. He also produced a large body of caricatures and drawings, as well as easel works.

1. Life and work.

Orozco was born into a middle-class family, and his early education was not centred on art. He was awakened to it as a student in Mexico City during the early 1890s, when he encountered José Guadalupe Posada and his popular satirical prints. Orozco studied architecture at evening classes in the Academia de S Carlos, but from 1897 to 1904 he trained as an agronomist and cartographer. He lost his left hand and his hearing and sight were impaired in an explosion during his early adolescence; the resentments and realism caused by physical handicaps affected both his political and artistic thinking.

He entered the Academia formally in 1906 and was subjected to its rigid, old-fashioned programme. This was ameliorated by the influence of the proto-Surrealist symbolism of the painting of one of his tutors, Julio Ruelas, and by the presence of Dr Atl (Geraldo Murillo). The latter saw the art of the past as something to emulate rather than copy and favoured the expressive anatomy of Michelangelo’s paintings over academic verisimilitude. Both tutors contributed significantly towards the development of Orozco’s taste in subject-matter and style.

During the Revolution, Orozco backed the constitutionalist Carranza government. These were difficult years for him: in 1911 his father died, and at the same time the students at the Academia went on strike in protest against the outdated teaching methods employed there. In 1914 Orozco fled with Dr Atl to Orizaba, Veracruz, where he remained until 1915 and drew cartoons for the political newspaper La Vanguardia. Throughout this period, fascinated with that tragic licentiousness bred by war and death’s familiarity, he produced a large number of studies of schoolgirls and prostitutes, as well as political caricatures. These he showed unsuccessfully in Mexico City in 1916 at the Librería Biblos. The next year he left for the United States, where on arrival Customs officers confiscated most of his drawings as indecent. After a discouraging and unprofitable stay in San Francisco and New York, he returned to Mexico City in 1919 and in 1923 married Margarita Valladares, by whom he had three children.

In the same year José Vasconcelos, the Minister of Education between 1921 and 1924 under President Obregón, invited Orozco to work in the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria in Mexico City with Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and other members of the fledgling mural movement. In 1924, political protestors damaged Orozco’s murals, and he was prevented from working there. In 1925 he painted the privately commissioned mural Omniscience at Mexico City’s Casa de los Azulejos, and early in 1926 he painted another fresco on the theme of Social Revolution at the industrial school in Orizaba, Veracruz. Later that year he returned to the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria and revised and completed his murals. Of the 20 or so panels he painted there, the most notable date from 1926, when he had perfected his large-scale drawing and fresco technique. These include The Trench, the Friar and the Indian and The Strike, the last of which incorporates the head of Christ from the earlier mural that it replaced, Christ Destroying his Cross (1924).

In 1927 Cristeros led a revolt against the anticlerical policies of the Calles government. Orozco went to the United States, where he remained until 1934. In New York he met Alma Reed, a writer and art dealer who became his patron and promoted his work for the rest of her life. She arranged exhibitions for him and opened her own gallery, Delphic Studios, in 1930 with a show of his easel paintings and gouaches. She also introduced Orozco to the Ashram, a salon led by Eva Sikelianos, who was devoted to the cultures of ancient Greece and modern India. At the Ashram he came to see the Mexican Revolution in more universal terms, through contact with the ideas behind Gandhi’s resistance movement in India, and learnt to apply Guy Hambidge’s system of ‘dynamic symmetry’ (a variation on the golden section) to his work; he also participated in readings of the Greek tragedies. All these factors influenced his subsequent murals.

In 1930 Orozco was commissioned to paint a mural by Pomona College in Claremont, CA. Strongly affected by the Prometheus of Aeschylus, he chose the theme of the god’s altruistic self-sacrifice for mankind in stealing fire from Zeus . He painted this mural early in the year, then returned to New York, where Alma Reed had arranged a commission for him at the New School for Social Research (where the American muralist Thomas Hart Benton was already painting). For this, the least expressive of his murals, he chose themes related to the political aspirations of the Ashram and composed images that contrasted revolution and human brotherhood. Orozco based the compositions on the principles of dynamic symmetry, which tended to diminish the fervour of the images.

In 1932 he was invited to paint a mural in the Baker Library at Dartmouth College in Hanover, NH. This is his largest work in the United States and depicts the evolution of civilization in the Americas. It is painted on the walls of a long reading-room, and assimilates rather than imposes the structures of dynamic symmetry. Beginning on an end wall with images of primordial migration and human sacrifice, it recounts the myth of Quetzalcóatl, the Pre-Columbian god, the brutalities of the Spanish conquest and modern revolution, and the ironies of modern education. The mural concludes at the far end of the room with pendant panels depicting the human sacrifice brought about by war and a wrathful Christ cutting down his cross, which symbolizes the ‘migration of the spirit’ in the modern world.

Returning to Mexico City in 1934, Orozco painted the mural Catharsis in the Palacio de Bellas Artes. In 1936, at the invitation of the Governor of Jalisco, he moved to Guadalajara to undertake three series of murals, which are considered to be his masterpieces. That year he painted Creative Man and the People and its False Leaders on the stage-walls and dome of the assembly hall of the University of Guadalajara. Between 1937 and 1938 he filled the great stair-well of the city’s Government Palace with his Hidalgo and National Independence. Lastly, in the vast Hospicio Cabañas, he covered the wall niches, vaults and dome of the former church with images of Mexico before and after the conquest, symbolizing the aspirations of humankind with his Man of Fire in the canopy of the dome. These murals display his vigorous style and iconography more forcefully than any of his other works.

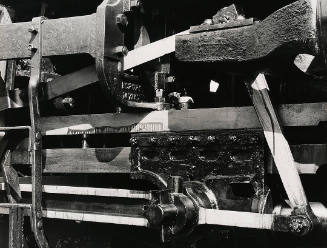

In 1940, in sharp contrast to the explosive scale and vivid colours of Guadalajara, he painted a series of essentially black-and-white murals depicting revolutionary scenes on the lateral walls of the Gabino Ortíz Library in Jiquilpan, Jalisco. The scenes culminate in an Allegory of Mexico painted in colour on the back wall. Later that year he went to New York, where he painted Dive Bomber and Tank in the Museum of Modern Art. In 1941 he completed a series of murals in the Supreme Court of Justice in Mexico City and between 1942 and 1944 began a series in the church of the Hospital de Jesús in Mexico City, on the theme of the Apocalypse, which remained unfinished. In 1947 he was given a retrospective exhibition in the Palacio de Bellas Artes, and from 1947 to 1948 he painted the abstract National Allegory on an exterior wall of the national school for teachers in Mexico City. During the last two years of his life he painted the frescoes Benito Juárez and the Church and the Imperialists for Chapultepec Castle in Mexico City and Hildalgo and the Great Mexican Revolutionary Legislation for the chamber of deputies of the state of Jalisco in Guadalajara.

2. Style and imagery.

With artists of genius, the style sometimes seems to be the opposite of the personality; with talents there is a closer compensatory match. Thus Diego Rivera’s childlike flamboyance contrasts with his work’s mature coherence, whereas the reckless rhetoric of David Alfano Siqueiros is constant both in life and in art. Orozco, a genius equal to Rivera but physically handicapped, personally retiring, decorous and ironic, painted with the vehemence of one too long held back. He was denied formal studies until the age of 24 and only travelled to Europe for three months in 1932. He struggled with little encouragement for more than half his life, discovering the roots of his art introspectively rather than in historical events or the art of others. Orozco’s themes are centred on the stark human suffering and social chaos induced by the idealist’s relentlessness. He was apolitical, obsessed with the ironies of that human comedy the events of the Revolution had spread before him, and personally identified with the victim; the radical realism of his work dramatizes only the details of atrocity and triumph while avoiding grandiose, abstract commentaries on human destiny. The power of his work derives from the scale on which he marshalled such detail. In this respect Orozco was the most original of the three main Mexican mural painters—the others being Siqueiros and Rivera—in dealing with the exigencies of architecture; he exploited its human scale in order to dramatize his motifs. This was accomplished by creating dynamic tensions between the architectural elements and the image, systematically excluding recessional space to emphasize the wall plane and contrasting small and large figures to establish hierarchies symbolizing their relative importance.

These formal elements are to be found from the very first major murals. In Prometheus (see fig. above) the chaotic masses react to the gigantic god’s theft of fire in an essentially undefined space. Similarly at the New School and Dartmouth College, and in the Catharsis fresco, although painted on long, unarticulated walls, the imagery constantly presses against the top and bottom edges, the major figures overwhelm the minor ones, and the imagery extends laterally and frontally but seldom into space. Thus, the viewer is bluntly confronted with the subject.

Nowhere in Orozco’s murals are these methods brought to such perfection as in his great stairway fresco at Guadalajara’s Government Palace. Ascending to the first landing one is confronted by an essentially black-and-white tumult of pierced and mutilated victims, one of which, with a handless arm ineffectually fending off a foot crushing its neck, is Orozco’s self-portrait. Above, and against a background of red flags and flame, a gigantic image of the Jesuit priest Miguel Hidalgo gradually appears across the ceiling of the stair-well (see fig.). Hidalgo led the 1810 revolt against Spanish rule and is portrayed with raised fist, sweeping a firebrand across the scene of carnage. The side walls of the two flights of steps ascending to the arches of the second level reveal scenes condemning the alliance of the clergy with the military and satirizing the ambitions of Fascism. Painted across and effectively masking the vaulting of the space, these dynamic images, set against a background of fire and smoke, completely arrest the spectator’s vision. The titanic scale of the figure of Hidalgo, looming on the ceiling, rivals the effect of a Pantocrator dominating the apse of a Byzantine basilica. Yet here there is no distance from the image, as there is with the Prometheus or the Man of Fire in the dome of the Hospicio Cabañas. It bears down with all the grim realism of a revolutionary artist’s expressive righteousness, allowing the viewer to escape neither anguish nor commitment. [Francis V. O’Connor. "Orozco, José Clemente." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 10, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T063949.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms