William Sidney Mount

William Sidney Mount

1807 - 1868

American painter. America’s first major genre painter and one of the most accomplished of his era (rivalled only by George Caleb Bingham), he spent most of his life on rural Long Island. He was apprenticed as a sign painter in 1825 to his brother, Henry Mount (1802–41), in New York. In 1826, frustrated by the limitations of sign painting, he enrolled for drawing classes at the newly established National Academy of Design, where he aspired to be a painter of historical subjects. His first efforts in painting were portraits; the historical scenes that followed, such as Saul and the Witch of Endor (1828; Washington, DC, Smithsonian Amer. A. Mus.), were similarly linear, flat, and brightly coloured. In 1827 he returned to live on Long Island, and from then onwards he alternated between the city and the country. He began to make the yeomen of Long Island his subject-matter, perhaps inspired by the popularity of engravings after David Wilkie and 17th-century genre painters.

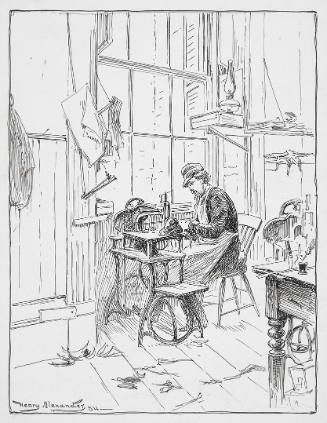

Mount’s first attempt at a genre painting, Rustic Dance after a Sleigh Ride (1830; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.), which he exhibited at the National Academy in New York that year, was a great success. It depicts a farm parlour full of dancing male and female ‘rustics’, lightly caricatured in their dress and expressions. Amusing as his New York audience found country manners, however, he soon realized that he could probe a deeper vein in this agrarian ideal (see fig.). On the one hand, Americans considered the landowning and hardworking farmer the ideal American; on the other, because political, social, and economic decision makers (and patrons of the arts) tended to be city people, they saw the rural citizen as a shrewd bumpkin. This characterization could also be referred back to the city dwellers. Mount’s first painting highlighting this comic discrepancy was so well received that it set the pattern for the rest of his career. His Bargaining for a Horse (1835; New York, NY Hist. Soc.) shows two farmers in a barnyard whittling to disguise their strategy in working out a deal. The negotiation is overtly for the horse near by, but in the new era of political bargaining and economic speculation that America had entered in the early 1830s, the painting also encouraged the viewer to laugh at many kinds of ‘horsetrading’ in which American citizens were involved.

Mount followed this huge success—the painting was engraved twice, once for the American Art Union—with a succession of paintings that were rooted in national self-criticism and popular expression. Farmers Nooning (1836; Stony Brook, NY, Mus.) embodied the apprehensions that were held about slavery and emancipation and highlighted the self-indulgent black worker as a major American labour problem. Cider-making (1841; New York, Met.) showed farmers directing all the phases of cider-making, a clever allegory for the party machinery of the Whigs, who had used cider (the drink of the ‘common man’) as one of their major symbols in the 1840 election campaign. Herald in the Country (or The Politics of 1852: Who Let down the Bars?, 1853; Stony Brook, NY, Mus.) shows a country man and a city man on opposite sides of a partially dismantled rail fence; the city man is reading a newspaper, The Herald, a clue that, alongside Mount’s alternative title, suggests the painting laughs at the Democratic election victory over the Whigs in 1852, a victory made possible by the huge influx of immigrants who voted Democrat. Although he himself was a Democrat, Mount in his paintings usually rose above party issues to laugh at the political process in general.

In many of his paintings, Mount turned to other themes of rural life. He created several works that celebrated rural music-making. One of his favourite formats was fiddle-playing (Mount was himself a violinist) or the fiddle-accompanied dance inside the country barn, visible from the outside of the barn through a large rectangular open door. In one of his best-known paintings in this format, The Power of Music (1847; Cleveland, OH, Mus. A.), a black person leans against the outside wall of the barn, absorbed in the attraction of the music. Mount was unusual in depicting the listener without caricature. Recognizing the attractiveness of this point of view, in the 1850s the art dealer William Schaus commissioned from Mount a number of images of black musicians for distribution in Europe as lithographs.

Mount received commissions from the most influential patrons in New York City, including Luman Reed and Jonathan Sturges (who took Farmers Nooning), and many of his works were engraved. He was a favourite of the newspaper and journal critics, who held him up as a model. The wit with which he carried out national self-criticism was unique among American artists; imitators such as Francis Edmonds and James Clonney failed to capture the spirit of his paintings. His clear draughtsmanship, small, precise brushstrokes, abstemious application of paint, and choice of bright colours all contributed greatly to his success. Extraordinarily selfconscious about painting methods, he kept journals in which he recorded experiments with pigments and brushes. He sketched extensively in notebooks and painted plein-air oil sketches for several works, devising a studio-wagon in which he travelled over Long Island. In his journals and extensive correspondence he considered a number of ideas for subjects. Although he made a large number of sketches of city characters, he only ever painted rural scenes, as these were what his audience wanted.

Mount never married. Throughout his life he continued to paint portraits; so many of them were posthumous that he once commented that his best patron was death. Although his genre paintings were very much in demand, he went for long stretches without painting—particularly after the Civil War—possibly because of the limited number of popular puns and concerns that he could exploit pictorially. [Elizabeth Johns. "Mount, William Sidney." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 9, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T060016.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms