William Strickland

William Strickland

1788 - 1854

American architect, engineer and painter. Among the first generation of native-born architects, he was an influential designer in the GREEK REVIVAL style. Over a period of almost 50 years he executed more than 70 commissions, many of them in Philadelphia. His last major building was the Tennessee State Capitol in Nashville, built from 1845.

1. Training and early work, 1803–25.

Through his father, a master carpenter who had worked on Latrobe’s Bank of Pennsylvania, Strickland was apprenticed to Benjamin Henry Latrobe in 1803, remaining in his office for about four years. During his apprenticeship he studied Latrobe’s folios of Greek antiquities, including James Stuart’s and Nicholas Revett’s Antiquities of Athens, 4 vols (1762–1816), as well as publications by the Society of Dilettanti. By 1807 he was in New York with his father, working as a painter of stage scenery. The following year he returned to Philadelphia, where he received his first major commission: a design for the city’s Masonic Hall (1809–11; destr. 1853; see Macmillan Enc. Archit., iv, p. 140). The Masonic Hall was a two-storey building in brick and marble, surmounted by a 60-m wooden steeple. This picturesque medley of pinnacles, buttresses, crenellations and niches, somewhat after the manner of Batty Langley’s Gothick, was an early example of American Gothic.

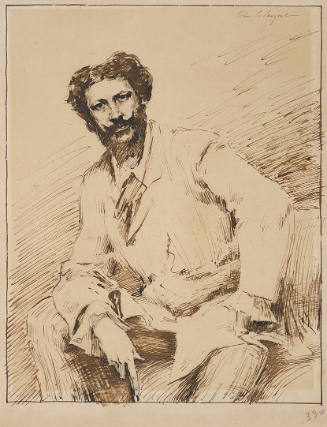

Despite the impressive design of the Masonic Hall and its technically innovative interior gas lighting, Strickland had no further architectural commissions after its completion. During the War of 1812 he worked on Philadelphia’s fortifications as a surveyor and engineer, and he also gained some success with his engravings and aquatints, providing plates for Port Folio and Analectic Magazine. Books illustrated by him included David Porter’s Journal of a Cruise Made to the Pacific Ocean and The Art of Colouring and Painting in Water Colours (both 1815). He also worked as a landscape painter and exhibited at the annual exhibitions of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts between 1811 and 1843. Among the pictures he exhibited was his view of Christ Church, Philadelphia (1811; Philadelphia, PA, Hist. Soc.).

In 1816 Philadelphia’s Swedenborgian community commissioned Strickland to design their Temple of the New Jerusalem (1816–17; destr.). The Temple supported a low dome with a lantern, and its elevations were decorated with pointed Gothic arches, but its plan followed the current fashion for centralized chapels and churches. Two years later Strickland won a competition to design the Second Bank of the United States in Philadelphia, ahead of Latrobe and other distinguished rivals. The bank’s directors required that the building be ‘a chaste imitation of Grecian Architecture, in its simplest and least expensive form’, and Strickland based his octastyle Doric porticoes at the north and south fronts on the Parthenon’s, as depicted in the Antiquities of Athens. For reasons of light and space, the Parthenon’s flanking colonnades were not copied in Strickland’s design, and the Second Bank’s interior featured a basilican hall of Ionic colonnades after that by Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, at his Assembly Rooms, York, England (1731–2). However, by preserving the templar block, and through its scale, proportion, siting and use of authentic detail, Strickland’s Second Bank was the purest Greek Doric building then to be seen in North America, and it was to play an influential part in subsequent American Neo-classicism.

The Second Bank resulted in a flood of commissions for Strickland over the next 20 years. He was also elected to various intellectual and cultural societies, including the Franklin Institute and the Musical Fund Society, and he designed the latter’s Hall (1824; altered) in Philadelphia. Elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1820, he also became a shareholder that year in the Athenaeum of Philadelphia. His work during this period already showed a strong vein of eclecticism. In 1820 he began rebuilding Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street Theatre (destr. 1850s), a building in the Federal Style (see FEDERAL STYLE, §1) with details in the manner of John Soane. Its ground-floor entrance arcade supported a Corinthian colonnade, echoing the design of numerous 18th-century town halls and theatres in England. In 1821 he made his first (six-month) trip to Britain, ostensibly to study prison architecture, although he was undoubtedly more interested in and influenced by his first-hand experience of English Palladianism and of Greek and Gothic Revival architecture. The Gothic influence can be seen in his St Stephen’s Episcopal Church (1822–3), Philadelphia, with its twin octagonal towers, while the effects of his study of Greek Revival architecture in England can be traced in his chaste Doric design (1824; unexecuted; see 1986–7 exh. cat., p. 68, fig.) for a Masonic Hall at Germantown, Philadelphia.

2. Mature work in Philadelphia and elsewhere, 1826–44.

Strickland’s abilities as an engineer, demonstrated by his land survey (1821–3) for the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal, for example, brought him to the attention of the Pennsylvania Society for the Promotion of Internal Improvement who sent him on a nine-month study tour of British transportation systems in 1825. The following year he published his Reports on Canals, Railways, Roads, and Other Subjects. Its 72 engraved plates further enhanced his reputation, but the Reports also helped spread the influence of advanced British technology through the USA. Supplemented by his correspondence, the Reports make it possible to document this second British trip and assess the impact on him of the cities he visited. His exquisitely graceful, yet broadly monumental designs of the 1820s and 1830s were often to reflect British Neo-classical architecture. After 1826 his series of commissions for Neo-classical buildings in Philadelphia transformed the city. One outstanding example is his US Naval Asylum (1826–33). Its broad, octastyle Ionic portico (from the Temple of the Ilissos as depicted by Stuart and Revett) serves as a foil for the broadly extended wings with their balconies on three storeys supported by cast-iron columns. These allowed fresh air to circulate more freely and were modelled after hospitals for service pensioners in London. His innovative use of structural cast-iron columns followed progressive British constructional practice.

Strickland pursued this successful blend of antique elements and modern construction and design. Over the next few years in Philadelphia he built the US Mint (1829–33; destr. 1902), the First Congregational Unitarian Church (1828; destr. 1885), the Mechanics’ Bank (1837; altered) and, in Rhode Island, the Athenaeum (1836) at Providence . He also continued with engineering projects, and between 1828 and 1840 he built the Delaware Breakwater that still protects Philadelphia’s harbour. He also made one of the first attempts in the USA at historic restoration when in 1828 he designed a wooden replica of Independence Hall’s original steeple, which had been removed in 1781.

Strickland’s effort to make Greek Revival architecture ever more acceptable as the national style is expressed at its best in his design for the Philadelphia (or Merchants’) Exchange (1832–4). Exploiting its triangular site, the building comprised both block and cylinder, for at its apex he added a dramatically curved Corinthian colonnade, ranging through the second and third storeys. This motif was derived from Charles Robert Cockerell’s Literary and Philosophical Institution (1821–3), Bristol, studied by Strickland on his visit of 1825. Rising from this cylinder was a lantern copied by Strickland from the Choragic Monument of Lysikrates, again via the Antiquities of Athens, but further authorized by a paraphrase of the same structure used for the Burns Monument, near Alloway in Scotland, and extolled for its beauty by Strickland in his letters of 1825. The Merchants’ Exchange stands as a monument to Strickland’s sensitivity to nuances of shape and form. Never rigidly doctrinaire, he used his understanding of the character of the Classical orders to create controlled grace.

The financial panic of 1837 resulted in a depression in the USA. With few commissions on offer, Strickland chose to travel to Europe with his family in 1838, visiting Britain, France and Italy, and documenting his travels with notes and watercolour sketches. On his return, his career for the next six years was desultory: engineer and urban planner (1838–9) for Cairo, IL, and minor Government commissions in Philadelphia and Washington, DC.

3. The last years: Nashville, 1845 and after.

Strickland was thus delighted in 1845 to be offered the appointment of architect for the Tennessee State Capitol in Nashville . This, his last major commission, was the culmination of his career. Begun in 1845 it was not completed until 1859. Dramatically sited on an urban hillside, it is composed of forceful, interlocking forms defined by an Ionic portico at each of the building’s four sides. These were derived from the Erechtheion in Athens, and a variant of the Choragic Monument of Lysikrates crowns the building. The State Capitol hints at the impending devaluation of Classical forms into isolated picturesque parts that was to characterize architectural design in the second half of the 19th century. A similar tendency is revealed in his other major project of this period, the Egyptian Revival First Presbyterian Church (1848–51), Nashville. Strickland had earlier experimented with the style in Philadelphia (e.g. his unexecuted proposal of 1836 for a gate at Laurel Hill Cemetery), but at Nashville’s First Presbyterian, motifs of great scale and height created an effect of precarious rigidity. Both this church and the State Capitol are symbols of style in transition. Strickland’s body was buried in a crypt beneath the State Capitol’s north portico. His son and assistant, Francis William Strickland, continued work on the unfinished building for two years until he was replaced in 1857. [Nancy Halverson Schless. "Strickland, William." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 11, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T081812.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms

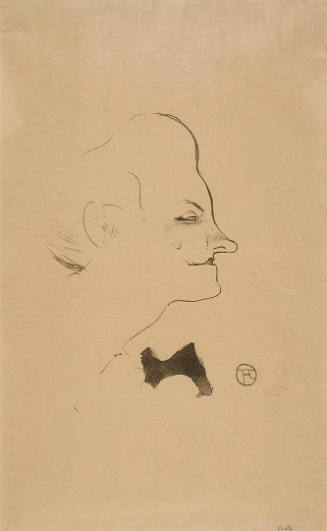

French, 1864 - 1901