George Caleb Bingham

George Caleb Bingham

1811 - 1879

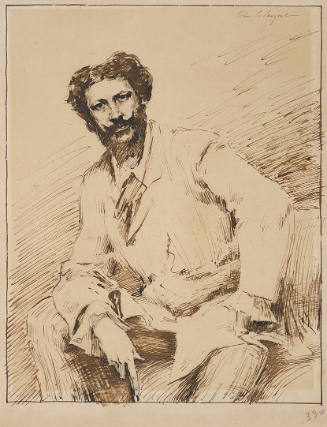

American painter. Raised in rural Howard and Saline Counties, MO, Bingham experienced from an early age the scenes on the major western rivers, the Missouri and the Mississippi, that inspired his development as a major genre painter. During his apprenticeship to a cabinetmaker, he met the itinerant portrait painter CHESTER HARDING, who turned Bingham’s attention to art. Teaching himself to draw and compose from art instruction books and engravings, the only resources available in the frontier territories, Bingham began painting portraits as early as 1834. The style of these works is provincial but notable for its sharpness, clear light and competent handling of paint.

Bingham travelled in 1838 to Philadelphia, where he saw his first genre paintings. He spent the years 1841 to 1844 in Washington, DC, painting the portraits of such political luminaries as Daniel Webster (Tulsa, OK, Gilcrease Inst. Amer. Hist. & A.). His roster of impressive sitters later enabled him to attract many portrait commissions. He settled back in Missouri at the end of 1844, and, although portraits would always form the greater portion of his work, it was over the next seven years that he made the outstanding contribution of his era to American genre painting. On the East Coast, Bingham’s slightly older contemporary William Sidney Mount had been exhibiting genre scenes of farmers since 1830. In the 1840s, however, the major focus of national concern shifted to westward expansion and its meaning for American society. Bingham’s work stunningly interpreted these concerns with three major motifs.

The first was that of the fur trader, which he developed in his painting Fur Traders Descending the Missouri (1845; New York, Met.). Against an imposing background of golden light and towering clouds, he placed a fur trader and his half-breed son (so identified in the original title of the painting), along with their chained bear cub, in a canoe floating downstream. Looking out at the viewer, the men seem thoughtful and cleanly dressed—not at all the uncivilized creatures described in contemporary literature. The surface of the water is mirror-like; reflections of the canoe, the oar and other details lock the scene into place. It is a romantic vision, transforming into a peaceful idyll the very terms of commercial gain in which the continent had been explored. The painting pays tribute to a vanishing phenomenon, for soon after the Panic of 1837 the market for pelts dropped disastrously and never recovered. As such, it epitomizes Bingham’s role in preserving, and reinterpreting, the vanishing West. Fur Traders is moreover characteristic of his style. His clearly delineated figures derive from character studies of frontier people that he had sketched on paper. He created a formal design, which conveyed an ordered, inviolate world (there exist no studies for his works other than drawings of individual figures); he painted smoothly, with an absence of brushstroke; and his tonalities were light, dominated by areas of bright colour and often, as in this painting, luminous.

Bingham’s second motif explored the life of the Mississippi raftsman. His Jolly Flatboatmen (1846; Detroit, MI, Manoogian priv. col.), again dominated by a clear light, is even more tightly organized than Fur Traders, with a number of figures balancing one another. This predilection for order, fundamental to Bingham’s very energies as an artist, contributed crucial meanings to his renderings of the West. These are often ironic meanings. No group of men on the western rivers seemed less responsible to society than the violent, fun-loving, gambling flatboatmen. He painted the flatboatmen in several versions, including scenes of dancing and cardplaying, for example Raftsmen Playing Cards (1847; St Louis, MO, A. Mus.), attracting audiences in St Louis and other western cities as well as in the East. His paintings transformed the terms in which frontier life had been understood, negating the threat of the rough frontiersman to civilized life. The American Art-Union, acting on a demand for this vision in the East during a period in which the nation was aggressively expanding westward, became Bingham’s major patron. In 1847 it engraved Jolly Flatboatmen for an audience of about 10,000 subscribers.

The final motif that Bingham explored was that of the election. No longer near the river (and the river’s associations with commerce and movement), these scenes take place in a village. Clearly influenced by Hogarth, but inspired by his own experience in politics, they show politicians arguing their point in Stump Speaking (1854), citizens casting their vote in County Election (1851 and 1852; one version in St Louis, MO, A. Mus.) and the electorate gathered to hear election results in Verdict of the People (1855; all three in St Louis, MO, Boatmen’s N. Bank). In each painting Bingham showed the wide range of social class, economic standing and apparent intellectual capability in the electorate; he chronicled political abuses as well—such as drinking at the polls and electioneering at the ballot box. Bingham exhibited County Election widely and painted a second version that was engraved by the Philadelphia engraver John Sartain (1808–97).

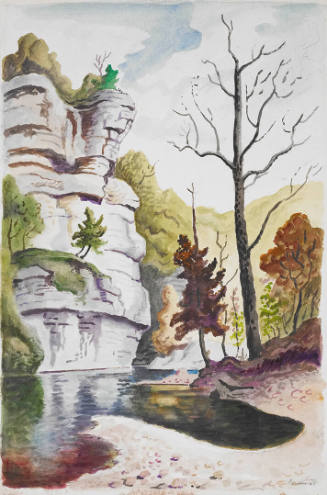

Although the genre scenes are Bingham’s major achievement, he also painted landscapes. His Emigration of Daniel Boone (1851; St Louis, MO, Washington U.), while inspired by the popularity of the theme rather than his own experience, pictured the early Western scout leading a caravan of settlers over the Cumberland Gap. In 1857 Bingham went to Düsseldorf, where he painted several large historical portraits on commission, notably one of Thomas Jefferson (destr. 1911). His angry historical painting protesting against the imposition of martial law in Missouri during the Civil War, Order No. 11 (1865–8; Cincinnati, OH, A. Mus.), is full of quotations from earlier works of art. Although Bingham was increasingly involved in state and local politics, he continued his work as a portrait painter. The major repositories for his paintings and drawings are the St Louis Art Museum and the Boatmen’s National Bank of St Louis. [Elizabeth Johns. "Bingham, George Caleb." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 3, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T008933.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms