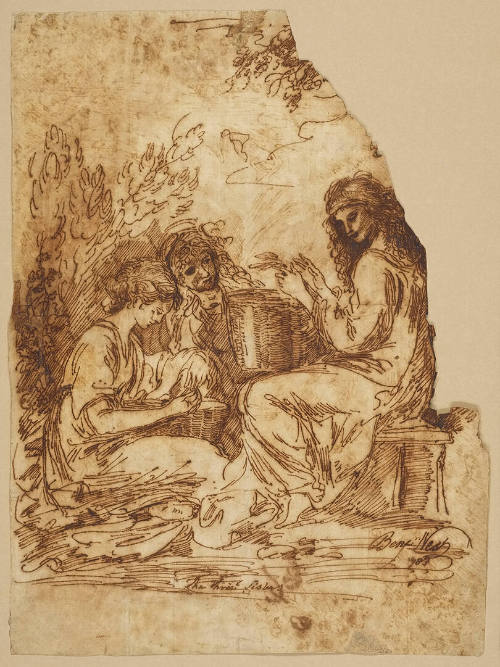

Benjamin West

Benjamin West

1738 - 1820

American painter and draughtsman, active in England (see fig.). He was the first American artist to achieve an international reputation and to influence artistic trends in Europe. He taught three generations of his aspiring countrymen. His son Raphael Lamar West (1769–1850) was a history painter.

1. Life and work.

(i) Early career, 1738–60.

He was one of ten children of a rural innkeeper whose Quaker family had moved to Colonial America in 1699 from Long Crendon, Bucks. In romantic legends perpetuated by the artist himself, he is pictured as an untutored Wunderkind. However, it has become clear that West received considerable support from talented and generous benefactors. West’s earliest known portraits, Robert Morris and Jane Morris (both West Chester, PA, Chester Co. Hist. Soc. Mus.), date from about 1752. He spent a year (probably 1755–6) painting portraits in Lancaster, PA, where one of his subjects, William Henry (Philadelphia, PA, Hist. Soc.), a master gunsmith, told him of a nobler art than painting faces—that of depicting morally uplifting historical and biblical episodes. West obliged him by painting the Death of Socrates (c. 1756; priv. col., see von Erffa and Staley, no. 4), which, notwithstanding its crude style and frieze-like composition, anticipated European Neo-classical painting by several decades. Rev. William Smith (1727–1803), principal of the College of Philadelphia, was so impressed by the work that he gave West informal instruction in Classical art, literature, and history.

In 1756, West moved to Philadelphia, PA, where he was taught by, among others, William Williams and John Valentine Haidt, a Moravian lay preacher who had been trained as a painter and metal-engraver. Williams lent West his landscapes to copy, as well as editions of Charles Alphonse Du Fresnoy’s De arte graphica and Jonathan Richardson’s An Essay on the Theory of Painting. West spent almost a year painting portraits in New York, hoping to earn enough to study in Italy. In 1760 two leading Philadelphia families, the Allens and the Shippens, gave him free passage to Italy and later advanced him $300 as payment for copies of Old Master paintings he was to make for them.

(ii) Italy and early years in England, 1760–92.

West embarked for Livorno in April 1760. E. P. Richardson described his journey as an act of profound importance to American art; West was the first American painter to transcend the boundaries of the Colonial portrait tradition, to enlarge the field of subjects that painting could deal with and eventually to take part in the great movements of Neo-classical and Romantic idealism that were to dominate European culture for the next 75 years.

West arrived in Rome in July. Personal charm, good looks, excellent letters of introduction, and his unique position as an American (and a presumed Quaker) studying art in Italy endeared him at once ‘in a constant state of high excitement’ to artistic society. Anton Raphael Mengs taught him at the Capitoline Academy and sent him to study art collections in northern Italy. He was made a member of the academies at Bologna, Florence, and Parma. Gavin Hamilton, who in the early 1760s was painting the first works in the Neo-classical style, spent time with West, no doubt conveying to him his enthusiasm for antiquity.

West arrived in England in August 1763, intending to make a short visit before he returned to America. He showed two Neo-classical works that he had painted in Rome, the Continence of Scipio (c. 1766; Cambridge, Fitzwilliam) and Pylades and Orestes (1766; London, Tate), at the Society of Arts exhibition of 1766, where they caused an artistic furore. ‘He is really a wonder of a man’, his patron, William Allen, wrote to Philadelphia, ‘and has so far outstripped all the painters of his time [in getting] into high esteem at once. … If he keeps his health he will make money very fast’ (see Kimball and Quinn). On the advice of his American patrons, he decided to stay in England. He married Elizabeth Shewell, the daughter of a Philadelphia merchant, in London in 1764. One of West’s admirers, Dr Robert Hay Drummond, Archbishop of York, asked him to paint an episode famous in Roman history, Agrippina Landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus (1768; New Haven, CT, Yale U. A.G.). West drew on his sketches and drawings of Classical dress, sculpture, and architecture to depict a moment frozen in history with a haunting sense of time, place, and actuality. He combined a cool palette with a severe composition and calculated gestures. The work created a sensation when it was exhibited in 1768. With this picture of Roman courage, grief, and conjugal virtue, West became at once the foremost history painter in England and the most advanced proponent of the Neo-classical style in Europe.

George III, who admired the picture, asked West to paint for him another episode from Roman history, the Departure of Regulus from Rome (1769; Brit. Royal Col.), and thereafter made him historical painter to the King with an annual stipend of £1000, which freed West from the need to support himself by painting portraits. The King commissioned West to paint 36 scenes depicting the History of Revealed Religion for the Royal Chapel at Windsor Castle. Although saints and the Virgin were excluded as subjects, they broke the Protestant barrier in English churches against ‘Popish pictures’. West completed 18 large canvases, including the Last Supper (1784; London, Tate). However, they were never installed, and remained in the artist’s studio until after his death. Between 1787 and 1789 he also painted for the King’s Audience Room at Windsor a series of vast canvases celebrating British victories during the Hundred Years’ War and the Foundation of the Order of the Garter (Brit. Royal Col.). West’s concern for accurate detail reflects the antiquarian research of Joseph Strutt and marks a considerable advance on earlier 18th-century history painting in England.

In 1771 West exhibited the Death of General Wolfe, the painting for which he is best known. Despite the advice of his peers and of the King, he painted Wolfe and his men as they were dressed at Quebec in 1759 rather than in Greek or Roman attire, although by including an Indian guide in the foreground he was able to display a more conventional talent for painting the nude. The work was an immediate popular and critical success; four replicas were commissioned (for example, 1770; Ottawa, N.G.), including one for the King. West’s achievement in bringing a new realism to history painting by his care in recording the exact details of the participants and their costume was widely recognized. Reynolds predicted that it would ‘occasion a revolution in the art’. At the same time the composition made a ready appeal to the emotions of the spectator by recalling the long tradition of the Christian Pietà. He followed a year later with another historical painting, William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians (1771–2; Philadelphia, PA, Acad. F.A.). West was one of the first artists to realize the commercial and publicity value of mechanical reproduction of his works: engravings of these paintings (by John Hall, 1775, and William Woollet, 1776) were sold by the tens of thousands in Europe and America.

(iii) President of the Royal Academy, 1792–1805.

In 1768 West and three other dissident officers of the Society of Artists, at the King’s suggestion and with his financial support, had drawn up an ‘Instrument of Foundation’ for a new association of 40 artists to be called the Royal Academy of Arts. Joshua Reynolds was the first president, and when he died in 1792, West was elected to succeed him. As President of the Royal Academy, the major recipient of the King’s patronage and the leading artist in Neo-classical and realistic history painting, West held a position of commanding authority in English art. His influence was further extended by what came to be known as ‘the American school’. Almost from the time of his arrival in London, West’s home and studio became a haven for American artists seeking advice, employment or instruction. Matthew Pratt, who stayed for two and a half years, was followed by a succession of other students remarkable both for their number and their talent. The first generation included Gilbert Stuart (his paid assistant for some four years), Charles Willson Peale, Ralph Earl, Joseph Wright, William Dunlap, John Trumbull, Robert Fulton (1765–1815), Henry Benbridge, and Abraham Delanoy (1742–95). Even West’s severest critics have allowed that he was an unfailingly kind and generous mentor, not only to Americans but also to English pupils. He made known his admiration for the early work of William Blake and Turner, and he gave Constable encouragement that was gratefully acknowledged. John Singleton Copley, though never his student, sought West’s advice on taking up a career in London.

West’s influence was extended as a discreet seller, trader, and collector of works of art. He was known to be the King’s buyer at auctions, was often consulted on appraisals, attributions, and prices of paintings and testified in some notable lawsuits involving artists’ fees and the quality of engravings. In 1779 he and a colleague were commissioned to place a valuation on 174 Old Master paintings in the collection of Robert Walpole at Houghton Hall in Norfolk (Walpole had urged Parliament to buy his entire collection, but Catherine II, Empress of Russia, acquired it at West’s price of £40,555). West engaged in a costly and unsuccessful speculative venture with his pupil John Trumbull in attempting to import Old Master works from France. His great triumph came in 1785, when he bought for 20 guineas at auction, amid general laughter, a dirty, wax-encrusted landscape, having identified it as Titian’s Death of Actaeon (c. 1562; London, N.G.).

West was able to keep George III’s favour throughout the American War of Independence (1775–83), despite his unconcealed sympathy for his rebellious countrymen. He was, indeed, almost a member of the royal household, with working rooms in Buckingham House and Windsor Castle. In the 1790s, however, he was criticized at the court for holding ‘French principles’ and for praising Napoleon Bonaparte. He incurred the dislike of Queen Charlotte, and George, intermittently ill after 1788, wavered in his friendship and support. In 1802, during the lull in the war with France, West made a five-week visit to Paris, where Napoleon met with him, and French artists, including David, paid him homage. Thereafter West’s stipend as history painter to the King and his History of Revealed Religion commission were cancelled. His troubles were further compounded by two improvident sons, the death of his ailing wife in 1814, heavy debts, a bad investment in American land, a decline in public favour, and a group of hostile Royal Academicians, including Copley, who in 1805 forced him to resign as President.

(iv) Later career, after 1805.

At 66 West accomplished a remarkable recovery. He found a new wealthy patron in William Beckford of Fonthill Abbey, Wilts. He scored a stunning popular success with the Death of Lord Nelson (1806; Liverpool, Walker A.G.). He surpassed that triumph with two huge religious paintings: Christ Healing the Sick in the Temple (2.74×4.27 m, 1811; London, Tate), which he painted over a ten-year period for the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia, was sold to the British Institution for the unheard-of price of 3000 guineas (four years later an ‘improved version’ was sent to the hospital; in situ); Our Saviour Brought from the Judgement Hall by Pilate to Caiaphas the High Priest, commonly known as Christ Rejected (5.08×6.60 m, 1814; Philadelphia, PA, Acad. F.A.), is still more ambitious in scale than Christ Healing the Sick (it includes more than 60 faces) and was greeted with great popular and critical acclaim. West introduced still another new direction in painting with his huge Death on the Pale Horse. Drawing on contemporary conceptions of the Sublime, it combines Christian imagery of the Apocalypse with pagan myth in a frenzy of movement that foreshadows Delacroix and the Romantic movement in European art. West introduced the Romantic style into portrait painting with his small General Kosciuszko in London (1797; Oberlin Coll., OH, Allen Mem. A. Mus.) and Robert Fulton (1806; Cooperstown, NY, Fenimore A. Mus). In 1806 he accepted the pleas of the Royal Academicians to resume the presidency and to restore harmony to the Academy.

West’s last years were productive and relatively peaceful. He testified before a government commission on the value of ‘those sublime sculptures’, the Parthenon Marbles (London, BM). He played a role in the founding of the British Academy, which became the National Gallery. He continued pioneering work he had undertaken in the new medium of lithography, having contributed to Specimens of Polyantography (1803). He achieved a new celebrity in 1816 with the publication of the first volume of his biography by John Galt. He welcomed, taught, and sometimes housed members of another generation of talented young American students, among them Washington Allston, Rembrandt Peale, Samuel F. B. Morse, Charles Bird King, Charles Robert Leslie, and Thomas Sully.

2. Reputation.

West’s reputation as an artist and teacher began to decline with his death. For more than a century, because of the weakness of his technique and lack of imagination in much of his work, his paintings were ignored or were cited as examples of all that was meretricious in art. Critical opinion began to change with a bicentennial exhibition of his work at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1938. He is generally recognized as ‘a stylistic innovator of immense influence’ and as the artist who first attempted to bring American art into contiguity with European art. [Robert C. Alberts. "West, Benjamin." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 15, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T091222.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms