Cyrus Edwin Dallin

Cyrus Edwin Dallin

1861 - 1944

American sculptor and teacher. The son of immigrant Mormons, Dallin was born in the rough pioneer town of Springville, UT. His talent was discovered at age 17, when he modeled two heads in white clay from a local mine. Exhibited at a territorial fair in Salt Lake City, these won the help of patrons who funded his trip to Boston in 1880 to study with sculptor Truman H. Bartlett (1835–1922). Although he settled in Arlington, MA, Dallin frequently returned to Utah; he twice traveled to Paris for study, from 1888–90 at the Académie Julian with noted sculptor Henri Chapu, and from 1896–9 at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts with Jean Dampt. He taught at Philadelphia’s Drexel Institute from 1895–6 and at the Massachusetts Normal Art School (now the Massachusetts College of Art and Design) from 1900 until his retirement in 1941. A charter member of the National Sculpture Society, he also received honorary degrees from Tufts University and Boston University.

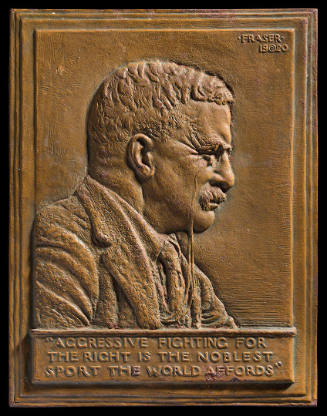

Dallin was a prolific sculptor who created portraits, ideal statuary and public monuments. Works such as Awakening of Spring (1891) and Apollo and Hyacinth (1896), preserved only in photographs, are typical of his early academic exercises. He sought a commercial market with plaster busts of Boston’s heroines Harriet Beecher Stowe and Julia Ward Howe, which could be purchased through P. P. Caproni & Brother beginning in 1915. Of the many models he submitted for competitions, relatively few were realized in any permanent medium; however, he contributed bronze portraits of Sir Isaac Newton (1895) to the Library of Congress, Washington, DC, and General Winfield S. Scott (1913) to the elaborate multi-figured Pennsylvania Monument at Gettysburg, PA. With Boston architect Clarence H. Blackall (1857–1942), he won the commission for the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument (1907–10) at Syracuse, NY, which was an enormous architectural plinth capped by a globe. Dallin contributed bronze reliefs to the monument: The Call to Arms (heavily indebted to the Departure of the Volunteers, Paris, 1830, by François Rude) and Incident in Gettysburg. The latter is an arresting image that juxtaposes stasis with violent movement: a soldier kneels in the foreground to repair a flagstaff; his comrades surge forward.

His connections with Utah yielded several commissions, among them the Angel Moroni, a hammered copper, gilded male bearing a trumpet that crowns the central spire of the Salt Lake Temple (1891; Salt Lake City), the Monument to Brigham Young and the Pioneers (1892–1900; Salt Lake City) and the Pioneer Mother (1932, Springville, UT). He also became a local favorite for projects in Massachusetts, including a relief, Signing the Mayflower Compact (1921; Provincetown), a depiction of colonial religious rebel Anne Hutchinson (1920; Boston) and a portrait of Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science (1922; Chestnut Hill, MA, Longyear Museum), but his equestrian Paul Revere (Boston) haunted his career. Modeled in 1883, with a revised model approved by the city of Boston in 1884, the work was delayed by stalled public subscriptions and local political problems. Dallin continued to revise the work, gradually subduing the dramatic animation of both horse and rider; it was dedicated, finally, in 1940.

Dallin’s greatest success was with his ideal subject: the American Indian. His Indian Hunter (1888, known only from photographs) relied heavily on the Classical Apollo Belvedere and won a gold medal at the American Art Association exhibition in New York. The huge popularity of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, which Dallin viewed in Paris in 1889, inspired him to undertake his first equestrian Indian. His Signal of Peace won an honorable mention at the 1890 Paris Salon; the bronze, cast at the sculptor’s expense, was exhibited at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Judge Lambert Tree purchased the work for Lincoln Park in Chicago.

During his second trip to Paris in 1899, Dallin created the Medicine Man, which won silver medals at the Exposition Universelle (1900) and at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, NY (1901); it was acquired by the Fairmount Park Art Association (Philadelphia). The Protest, a colossal equestrian statue made out of staff (a type of plaster), won a gold medal at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, but only small replicas were cast. Appeal to the Great Spirit (1909) was initially conceived as an allegory with a resigned Indian and an aggressive Indian flanking the central figure, but the final version is of a single equestrian figure who dramatically extends his arms in prayer and gazes upward (Boston). Dallin sustained this success with The Scout (1914; Kansas City, MO, Penn Valley Park), which won a gold medal at San Francisco’s Panama Pacific Exposition in 1915. In addition to these equestrian Indians, Dallin created monumental bronzes of the Menotomy Indian Hunter (1911, Arlington, MA, Robbins Park) and Massasoit (1920, Plymouth, MA), both of which honor the original Native American inhabitants of Massachusetts. Casts of these works, along with portraits of Chief Sitting Bull, Chief Joseph, Geronimo, anonymous Indians, an ideal portrait of Sacagawea and genre subjects such as Indian Archer and Peace Pipe were available in different sizes in bronze from Gorham Bronze Company.

Dallin had grown up with Indian playmates in Utah and had first-hand knowledge about them as well as sympathy. He avoided many of the stereotypes of his day, but his work tended to play out a familiar type of the noble savage threatened by white civilization. This theme had a long history in American sculpture, evidenced by conspicuous works at the nation’s Capitol such as Horatio Greenough’s The Rescue (1836–53; destr.) and Thomas Crawford’s Progress of Civilization (1863). Subsequently, John Quincy Adams Ward (1830–1910) explored the possibility of naturalistic genre in his Indian Hunter (1864; New York), and Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907) based his pensive marble Hiawatha (1874; New York, Met.) on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem. Like Dallin, Frederic Remington (1861–1909) capitalized on casting technology to produce small-scale bronzes depicting Native Americans, but with sensationalized subjects as The Scalp (1898), Horse Thief (1907) and The Savage (1908).

Dallin’s aims were different; he did not depict the savage, instead he envisioned Indian heroes. His portraits of Native Americans are direct, terminating bluntly at the neck; standing figures often exceed life-size (Massasoit is approximately 2.9 m tall) and fuse striking naturalism with classical contrapposto poses. In the final version of Paul Revere, Dallin relied on historical conventions for equestrian statuary to balance the movements of horse and rider (Revere swivels to his right, his right arm extended; the horse’s upraised left hoof counters the rider’s gesture). However, his Indians ride ponies, firmly anchored to the ground, their poses static. In Appeal to the Great Spirit, the rider’s expressive gesture is mirrored only in the angle of the pony’s ears; in Medicine Man, the upraised right arm of the rider finds a counterpart in the stride of the steed, but the directional weight of the sculpture is thrown entirely to the left side of the rider. Dallin’s Indians may perhaps be linked with the prevailing nostalgia for an old, mythical West, but his best work departs from existing stereotypes. [Janet A. Headley. "Dallin, Cyrus." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 8, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T2086844.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms

Taos Pueblo, 1906 - 1993