David Wilkie

Image Not Available

for David Wilkie

David Wilkie

British, 1785 - 1841

1. Life and painted works.

(i) Scotland, 1785–1805.

Wilkie may have inherited his rectitude and tenacity, even his nervous inhibitions, from his father, the minister of his native parish. Though little responsive to schooling, he showed an early inclination towards mimicry that expressed itself in drawings, chiefly of human activity. In these he was influenced by a copy of Allan Ramsay’s pastoral comedy in verse, the Gentle Shepherd (1725), illustrated by David Allan in 1788. One of the few surviving examples of his early drawings represents a scene from it (c. 1797; Kirkcaldy, Fife, Mus. & A.G.). Wilkie cherished the demotic spirit of this book and its illustrations throughout his life.

By 1799 Wilkie had determined to become a painter, and in that year, despite parental misgivings, he entered the Trustees’ Academy in Edinburgh. The curriculum devised by the Academy’s Master, John Graham (1754/5–1817), included exercises in history painting. Wilkie’s two suriving essays in this genre, Diana and Callisto (1803–4; Norfolk, VA, Chrysler Mus.) and Patie Disbelieves Sir William’s Prophecy (1803; Duke of Buccleuch priv. col.), both show his unwillingness to subordinate his gift for the vivid observation of everyday life to the academic conventions of history painting. He left the Academy in 1804.

In 1803 Wilkie began to produce pot-boiler portraits of middle-class men and women from his own part of Fife. Most were painted in the manner of Henry Raeburn; in the finest, William Bethune-Morrison with his Wife and Daughter (1804; Edinburgh, N.G.), observation again prevailed over stylistic convention. Although he was obliged to continue painting portraits to support himself, he recognized that neither history nor portrait painting was his true vocation. In 1804–5 he painted his first genre piece, Pitlessie Fair (Edinburgh, N.G.), a human panorama set in his native parish. This assemblage of commonplace incident was based on 17th-century Dutch and Flemish prints and on a shrewd study of his social surroundings. The picture was the key to Wilkie’s subsequent development. While it contains the germ of many later compositions, it also brought home to the artist his lack of training. In search of the competitive stimulus of other painters and a wider market for his work he travelled to London in 1805.

(ii) London, 1805–25.

Wilkie enrolled as a student at the Royal Academy and in 1806 exhibited the Village Politicians (Scone Pal., Tayside), which brought him instant fame. Further success came with the exhibition of the Blind Fiddler (1806; London, Tate) in 1807 and the Rent Day (1807–8; priv. col.; engraved by Abraham Raimbach, 1817) in 1809, which were bought by Sir George Beaumont and Henry Phipps, 1st Earl of Mulgrave (1755–1831), respectively. Although these paintings were still, albeit decreasingly, dependent on David Teniers (ii) and 17th-century genre painting, they were perceived as marking a new artistic era. Wilkie’s originality lay less in his opposition to current academic values than in his artful individualizations of character and manipulation of detail, and in his ability to relate figures together with a psychological realism which went beyond the 18th-century tradition of sentimental genre represented by Thomas Gainsborough and George Morland. His penetration of human expression, which extended to the subtlety of mixed emotions, was helped by his knowledge of acting and of Charles Bell’s Essay on the Anatomy of Expression in Painting (1806). Although a penetrating and persistent student of nature (as witnessed by drawings which rank among the highest in British draughtsmanship), Wilkie also sometimes used small clay models, set as if on a stage, in composing and lighting his groups.

The evolution of Wilkie’s style was always unsteady and at times reversionary. In Village Festival (1809–11; London, Tate) and Blind Man’s Buff (1812; Brit. Royal Col.) he paid a new attention to the plasticity of form, binding figures together in groups and introducing more colour and fluidity of paint. In this the modulating lights of Adriaen van Ostade and Rembrandt played a part. From 1809 he employed John Burnet and Abraham Raimbach among others to produce line-engravings after his paintings. As he justly calculated, these prints both popularized his work and gave it a surer economic footing. In 1809 he was elected an ARA and in 1811 an RA.

Wilkie’s art reached maturity around 1813, beginning with pictures of a relative emotional quietude, softer modelling and a yellowy overall tone, for instance Letter of Introduction (1813; Edinburgh, N.G.) and Distraining for Rent. Later, emotions became more sharply expressed, shadows deeper, colour stronger, the paint more unctuous and the touch more broken, for example Duncan Gray (1819; Edinburgh, N.G.) and the Penny Wedding. He acknowledged his debt to Rembrandt more directly in Bathsheba (1817; Liverpool, Walker A.G.). During this time Wilkie had visited Paris (in 1814 and 1821) and the Low Countries (in 1816), where his study of Rembrandt was complemented by that of Titian and Rubens. His search for a freer and less exhausting technique was imposed in part by the need to keep abreast of his undiminishing but sometimes burdensome success.

The culmination of this period was Chelsea Pensioners Reading the Gazette of the Battle of Waterloo (1818–22; London, Apsley House), commissioned by the Duke of Wellington. To the public it was his triumph, a summary of his anecdotal power, expressive of patriotic sentiment in a classless pictorial language. At the 1822 Royal Academy it received the unprecedented honour of a protective railing. In the same year George IV made a state visit to Edinburgh, the first by a sovereign of the United Kingdom. As ever ambitious, and urged by an unbroken attachment to his native country, Wilkie went to Edinburgh to observe this piece of pageantry. The result was the long-laboured Entrance of George IV into Holyrood House (1823–30; Edinburgh, Pal. Holyroodhouse, Royal Col.), a painting of contemporary history which he preferred to describe as one of his ‘portraits in action’. On the death of Raeburn in 1823 Wilkie was appointed King’s Limner for Scotland, an office that involved the execution of ceremonial portraits.

To the professional anxieties of a naturally anxious man were added, late in 1824, two personal tragedies: the deaths of his mother, the centre of his domestic life in Kensington (he never married), and of two brothers with dependent children. He suffered a nervous breakdown and was advised to recuperate by travelling.

(iii) Travels and later life, 1825–41.

Wilkie left London in July 1825, arriving in Rome in November, where he stayed until February 1826, discovering, notably, the frescoes of Raphael. In 1826 he travelled widely, making prolonged stays in Naples, Parma, Venice, Munich, Dresden, Vienna and Florence. In Parma and Dresden he made a study of Correggio.

He was in Rome from December until April 1827 and cautiously began to paint again. In May 1827 he left for Genoa to buy portraits by Anthony van Dyck for Sir Robert Peel, before spending the summer in Geneva. He then undertook the uncommon venture of visiting Spain and was in Madrid from October until March 1828, studying Velázquez and Titian. In April he went to Seville to study Murillo and returned to London in June.

Back in England, Wilkie began what seemed a new career. He had been away for three years and felt that it should not be seen that he had, in his own words, visited ‘Italy and Spain for nothing’. His experience abroad had deepened his understanding of the grand tradition, although he remained faithful to his earliest models, combining his appreciation of Correggio with that of van Ostade, and of Velázquez with that of Teniers (ii).

In 1829 he exhibited eight pictures at the Royal Academy, an unprecedented number for him. Four of these represented aspects of popular religious life observed in Rome during the Holy Year, including Cardinal Washing Pilgrims’ Feet (1826–7; Glasgow, A.G. & Mus.); three celebrated the recent Spanish struggle for independence, for example the exceptionally bold Siege of Saragossa (1828; Brit. Royal Col.); and one was his first full-scale public portrait, Thomas Erskine, Ninth Earl of Kellie (1824–5 and 1828; Cupar, Fife, County Hall), which had been commissioned by his native county of Fife. George IV bought five of these pictures, a deliberate act of generosity which confirmed Wilkie’s popularity among the highest ranks of aristocratic patrons. In 1830 Wilkie succeeded Thomas Lawrence as Painter in Ordinary to the King, a post he retained under William IV (by whom he was knighted in 1836) and Queen Victoria. Although he painted a few striking portraits of royalty, for example William IV (1832–3; London, Apsley House), and of men of rank and position, he remained apprehensive about portraiture. Some of his best portraits of this later period were private commissions, for instance William Esdaile (1836; priv. col., see Burl. Mag., civ (1962), p. 116).

Wilkie’s other works of the period tended towards historical anecdote. Generally larger than before, fluent, and ambitiously rich in painterly effect, they contain a relatively restricted number of figures, presented with a new amplitude. A few display his interest in the tableaux-vivants he had seen on his Continental travels, which had become fashionable in London. Typical are Columbus at La Rabida (1834–5; Raleigh, NC, Mus. A.), Napoleon and the Pope (1835–6; Dublin, N.G.) and Josephine and the Fortune Teller (1836–7; Edinburgh, N.G.). The supreme example is Sir David Baird Discovering the Body of Sultan Tippoo Sahib. Closer in style to his earlier work, but with added sweetness of feeling, are such pictures as First Ear-ring (1834–5; London, Tate) and Peep-o’-day Boys’ Cabin (1834–5; London, Tate), the product of a foray after topical picturesque novelty in the west of Ireland in 1835. (The Lowland Wilkie had sought similar novelty in the Scottish Highlands in 1817 and in Spain in 1827.) ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’ (1836–7; Glasgow, A.G. & Mus.), a subject from Robert Burns, and John Knox Dispensing the Sacrament (two versions, the first begun 1838, both left unfinished 1840; Edinburgh, N.G.) reveal Wilkie’s renewed faith in his cultural roots.

Wilkie’s work from 1828 had a mixed reception. Many admirers of his earlier more domestic manner, which they had likened to the poetry of George Crabbe and novels of Walter Scott, were disconcerted by his homage to the Old Masters studied on his travels in southern Europe. Like Joshua Reynolds, whom he admired, Wilkie was always curious about the technical mysteries of painting. Much of his later work, particularly where he used bitumen to create an impression of Old-Masterly richness, has now altered in appearance and is difficult to judge.

Wilkie’s admiration for Italian art reached back to Giotto, and his tendency to find virtue in both the life and art of the past had a bearing on the last journey of his life. In 1840 he left to study the people of the Holy Land. Travelling overland via the Danube and Constantinople, he arrived in Syria in early 1841 and remained in Palestine until April, with five weeks in Jerusalem. Although no finished paintings survive from this period, he made oil sketches, which included a Christ before Pilate (1841; priv. col., see 1958 exh. cat., p. 39), conceived in terms of contemporary life. He returned through Alexandria, where he painted a small portrait, Mehmed Ali (1841; London, Tate). He died on his way back to London and was buried at sea. Turner paid tribute to his friend and rival in Peace: Burial at Sea (London, Tate).

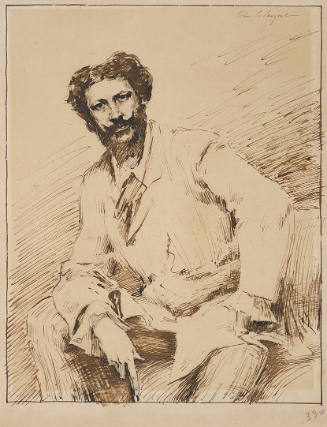

2. Drawings.

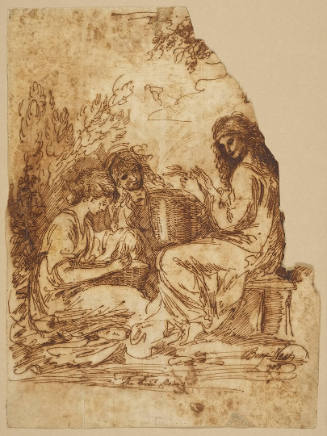

Wilkie was a prolific and assured draughtsman in the great European tradition of figure drawing. He was particularly influenced by the trois crayons manner of Rubens, which he applied to highly finished portraits and such figure drawings as Study of a Female Nude (c. 1815; Oxford, Ashmolean). The bulk of his drawings relate directly to his paintings. For major early works like Pitlessie Fair he produced chalk or pencil sketches characterized by an uncertain line and absence of contrasting tone, through which he sought to establish elements of the composition (e.g. Edinburgh, N.G.). He was rarely a simple recorder of nature or the specifics of contemporary life, preferring to use drawings to capture a fleeting expression or a compelling pose, for example in A Woman Tiring her Hair (Oxford, Ashmolean), which developed out of a sketch for Chelsea Pensioners (Oxford, Ashmolean). Increasingly, he explored the dramatic possibilities of chiaroscuro in Rembrandtesque pen, ink and wash drawings such as The Burial of the Scottish Regalia (c. 1835; U. Glasgow, Hunterian A.G.).

Wilkie’s drawings grew larger and more elaborate as his style developed. Mature works such as A Lantern-bearer and Figures (c. 1835; London, V&A) combine softly modelled chalk and freely washed watercolour backgrounds. The many intensely coloured drawings produced on his final trip to the Middle East—studies of both local costume and character (e.g. Portrait of Sotiri, Dragoman of Mr Colquhoun; Oxford, Ashmolean; see also Portrait of Abram Incab Messir)—are among his finest graphic achievements. [Hamish Miles. "Wilkie, David." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 15, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T091600.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms