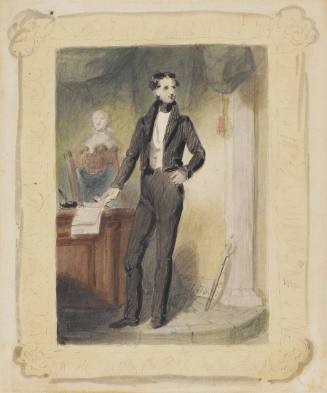

John Singleton Copley

John Singleton Copley

1738 - 1815

American painter. Copley was the greatest American artist of the Colonial period, active as a portrait painter in Boston from 1753 to 1774. After a year of study in Italy and following the outbreak of the American Revolution, in 1775 he settled in London, where he spent the rest of his life, continuing to paint portraits and making his reputation as a history painter.

1. America, 1738–73.

Copley’s parents, Richard and Mary Copley, probably emigrated from Ireland shortly before he was born. Following the death of his father, a tobacconist, Copley’s mother in 1748 married PETER PELHAM, an engraver of mezzotint portraits. Copley was undoubtedly influenced by Pelham and through him would have had contact with other artists working in Boston, including JOHN SMIBERT, whose collection of copies of Old Master paintings and casts after antique sculpture constituted the closest thing to an art museum in Colonial America.

Copley began to produce works of art by 1753, when he was only 15. He painted a few early history paintings, largely copied from engravings, but there was no demand for such pictures in Boston. From the beginning he painted primarily portraits. His early style reflects the technical influence of Smibert and the formal influence of a younger artist active in Boston in the late 1740s, ROBERT FEKE. Working in relative isolation, he also relied on English prints for compositional ideas. The portrait of Mrs Joseph Mann (1753; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.), for example, exactly reverses the composition of an English mezzotint of Princess Anne by Isaac Beckett after Willem Wissing (c. 1683).

The death of Smibert and Pelham in 1751, and the departure of Feke and John Greenwood, left Copley little competition in Boston at the start of his career. In 1755, however, a more polished British painter, JOSEPH BLACKBURN, arrived, whose work made Copley’s paintings seem pedestrian. Copley quickly absorbed Blackburn’s Rococo style of colour, composition and elaborate drapery, but he retained a strong sense of the physical individuality and presence of his sitters that differs from Blackburn’s sweet, sometimes cloying, characterizations.

Whereas Copley’s portraits of the 1750s were based on mezzotints after late 17th- and early 18th-century English paintings by Godfrey Kneller and others, in the early 1760s Copley became indebted via mezzotints to the later English artist THOMAS HUDSON. He painted in an English style that was about 15 years out of date, enhanced by characteristics that were fundamental to his developing personal style—simplicity of design, fidelity of likeness, restrained but bold use of colour (Copley was a superb colourist throughout his career), strong tonal contrasts (the mark of an artist trained more through the study of black-and-white prints than of subtly modulated paintings) and a concern more with two-dimensional surface pattern than with the illusionistic representation of masses in space. He painted a few full-length portraits, but most were standard half-lengths (50×40 in.), kit-cats (36×28 in.) or quarter-lengths (30×25 in.). He was an excellent craftsman, preparing his materials with care, and his pictures have stood up well to the passage of time. He was fastidious in the studio and, to the annoyance of some sitters, worked slowly, although he could turn out one half-length or two quarter-length pictures per week. By the mid-1760s Copley was influenced by more recent sources, notably by JOSHUA REYNOLDS; Copley’s portrait of Mrs Jerathmael Bowers (1767–70; New York, Met.) was based on James McArdell’s mezzotint of Reynolds’s portrait of Lady Caroline Russell (1759).

Copley prospered by satisfying the taste of his American Colonial sitters for accurate likenesses. But wealth was not sufficient. Aware that he was the best artist in Boston, and perhaps in all of America, Copley yearned to know how good his art was by European standards. In 1765 he painted a portrait of his half-brother Henry Pelham, the Boy with a Squirrel (Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.), and sent it to London to be exhibited at the Society of Artists the following year. Reynolds and Benjamin West were favourably impressed, but some criticism was directed at the picture’s flatness, and Copley was urged to come to England to perfect his art. He was reluctant, however, to give up a flourishing and profitable business in Boston. During the next few years he painted some of the most brilliant and penetrating portraits of his career. The portrait of Paul Revere (1768; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.) shows a shirt-sleeved silversmith with his engraver’s tools spread on the table before him, contemplating the decorative design he will incise into the surface of a teapot. This portrait is a splendid example of the way in which Copley exercised control of light and colour to achieve a triumph of realistic portraiture.

In 1769 Copley, by then quite prosperous, married Susanna Clarke, the daughter of Richard Clarke, the agent of the British East India Company in Boston. He purchased a 20-acre farm with three houses on it next to John Hancock’s house on Beacon Hill. To mark the marriage, Copley painted a pair of pastel portraits of himself and his wife (1769; Winterthur, DE, du Pont Mus.). Although self-taught, Copley was a superb pastellist, one of the best in a century in which the pastel portrait was very popular in England and on the Continent (e.g. Hugh Hall, 1758; New York, Met.). Many of Copley’s wealthiest sitters, especially those who were young and socially prominent, opted for pastels rather than oils. Copley was also a first-rate painter of miniatures, both in watercolour on ivory and oil on copper (e.g. The Rev. Samuel Fayerweather, c. 1758; New Haven, CT, Yale U. A.G.).

The political events of the late 1760s and early 1770s split Copley’s clientele into opposing camps. Some of his friends and patrons became ardent Whigs, others intractable Tories. Copley was divided in his sympathies. He was a long-time friend of many radicals, including Paul Revere, John Hancock and Sam Adams. On the other hand, he now moved in prominent social circles, and all of his merchant in-laws were Loyalists. Copley also found his business in Boston falling off. In 1771 he took his only extended professional trip in Colonial America, spending over six productive months painting in New York. Copley had by then achieved a powerful, restrained, sophisticated and austere style that had no precise English counterpart; he had, in fact, created an original American style (e.g. Gulian Verplanck, 1771; New York, Met.). Sombre in hue and deeply shadowed, his late American portraits, such as that of Mrs Humphrey Devereux (1770–71; Wellington, Mus. NZ, Te Papa Tongarewa) and Mrs John Winthrop (1773; New York, Met.), are among his most impressive achievements. In the 1770s they directly influenced younger American artists, especially John Trumbull, Gilbert Stuart and Ralph Earl, generating the first definably American style—a development that was unfortunately cut short by the outbreak of the American Revolution and the departure of all these artists for England for the duration of the war.

The political situation in Boston worsened after the Boston Tea Party (1773). The tea had been consigned to Copley’s father-in-law, and Copley unsuccessfully attempted to conciliate both his Tory in-laws and his radical friends. Reluctant to offend either party by taking sides, he decided to go to Europe to improve his art.

2. Europe, 1774–1815.

Copley left Boston early in 1774. After a brief stay in England, where he finally met and was befriended by BENJAMIN WEST, Copley travelled via France to Italy, where he studied for a year. Exposed to works of Classical antiquity and the Old Masters, he overcame earlier apprehensions regarding multi-figure compositions. His new assurance is manifest in the Ascension (1775; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.), inspired by Raphael’s Transfiguration. By the end of 1775 Copley was back in England and reunited with his family, who had left Boston after the outbreak of hostilities. A large group portrait of The Copley Family (1776–7; Washington, DC, N.G.A.) commemorates the reunion.

At the age of 37 Copley launched a second career in England. He hoped that he would be able to concentrate on history painting, fulfilling an early ambition stimulated by reading books on art theory to work in the highest branch of art, although he continued to paint portraits to support his family. His English portrait style, as in Richard Heber (1782; New Haven, CT, Yale Cent.) or in the portrait tentatively identified as that of Mrs Seymour Fort (c. 1778; Hartford, CT, Wadsworth Atheneum), was influenced by West, Reynolds and George Romney and appears looser than his American manner. Supple brushwork applied the paint fluidly to the canvas, dissolving detail in favour of more flamboyant visual effects. Strong contrasts of light and dark continued to be important but were used to open up space as well as to enliven the surface.

Watson and the Shark (1778; Washington, DC, N.G.A.), Copley’s first English history painting, drew favourable attention when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1779, the year in which he was elected RA. The painting reflected Copley’s admiration for what Edgar Wind later called ‘the revolution of history painting’ (J. Warb. & Court. Inst., ii (1938–9), pp. 116–27), a break with tradition that had been initiated by Benjamin West’s Death of General Wolfe (1771; Ottawa, N.G.) through portraying recent events in contemporary rather than classical terms. Copley’s next history painting, the Death of the Earl of Chatham (1779–81; London, Tate), carried the innovations in history painting a step further, combining history painting and portraiture (genres that had traditionally been separate) and incorporating portraits of 55 of England’s most prominent noblemen. Viewing himself as a historian as well as an artist, Copley was trying to record an important event for posterity.

While the Death of Chatham was being exhibited, Copley began to work on another large history picture, the Death of Major Peirson (1782–4; London, Tate). On 5–6 January 1781 a detachment of 900 French troops had invaded the island of Jersey, seizing the capital city of St Helier and most of the island. Inspired and led by a 24-year-old major, Francis Peirson, the remaining British troops and local militia launched a brisk counter-attack that swept back into St Helier and won the day. Peirson was shot and killed at the moment of his triumph. That event, and the revenge exacted by Peirson’s black servant, is the primary subject of the picture. The Death of Major Peirson is Copley’s finest history painting, notable for its vigorous composition, brilliant colour and flickering contrasts of light and dark. Like Watson and the Shark, it contains a topographically accurate townscape, the portrait of a black as a central figure and the representation of a dramatic event. Like the Death of Chatham, it is centred on a death group and includes actual portraits of key figures. Although Copley had no pupils and founded no school, such paintings influenced John Trumbull’s series of American Revolutionary War scenes (New Haven, CT, Yale U. A.G.). Thus the large English history paintings that Copley regarded as his major achievement did have some impact, albeit not profound or durable, on the subsequent course of American art. It is also possible that through engravings his history paintings may have had some influence on later French Neo-classicism, particularly such portrait-filled recordings of contemporary history as Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Tennis Court (1790–91; Paris, Louvre) with its echoes of the Death of Chatham.

In 1783, while at work on the Death of Major Peirson, Copley and his family moved from Leicester Square to an elegant house in George Street, where he lived for the rest of his life, as did his son John Singleton Copley jr, later Lord Lyndhurst, three times Lord Chancellor under Queen Victoria. Unfortunately, the quality of his art and indeed of his life deteriorated after the triumph of the Death of Major Peirson. In 1783 he won a commission from the Corporation of the City of London to paint the Siege of Gibraltar (London, Guildhall A.G.), an enormous canvas (5.5×7.6 m) celebrating a victory over the Spanish (1782). Shortly thereafter he also received his first major royal commission, the Daughters of George III (London, Buckingham Pal., Royal Col.). But when this work was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1785, it was ridiculed by a rival artist, John Hoppner (review repr. in W. T. Whitley, Artists and their Friends (Cambridge, 1928), ii, p. 49), and Copley subsequently received little royal or aristocratic patronage. Another blow in 1785 was the sudden illness and death of his two youngest children. The Siege of Gibraltar, long delayed in its completion, was not a critical success when it was finally exhibited in 1791.

During the 1790s Copley attempted to apply his realistic history painting techniques to scenes of 17th-century English history, but the results failed to capture the public imagination. He did produce one final impressive modern history picture, the Victory of Lord Duncan (1798–9; Dundee, Spalding Golf Mus.), but thereafter his powers declined rapidly. In the early years of the 19th century he became enmeshed in squabbles with patrons and fellow artists, especially during an unfortunate campaign to unseat West as PRA. He sank into debt in attempting to maintain his elegant house and grew increasingly feeble in both mind and body until, following a stroke, he died at the age of 77. [Jules David Prown. "Copley, John Singleton." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 4, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T019336.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms