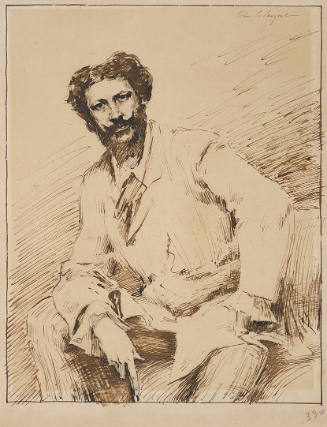

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

French, 1841 - 1919

French painter, printmaker and sculptor. He was one of the founders and leading exponents of IMPRESSIONISM from the late 1860s, producing some of the movement’s most famous images of carefree leisure. He broke with his Impressionist colleagues to exhibit at the Salon from 1878, and from c. 1884 he adopted a more linear style indebted to the Old Masters. His critical reputation has suffered from the many minor works he produced during his later years.

1. Life and work.

(i) Early career.

Renoir was born in Limoges but lived with his family in Paris from 1844. The sixth of seven children, he came from a humble background; his father, Léonard Renoir, was a tailor and his mother, Marguerite Merlet, a dressmaker. At the age of 13 he was apprenticed to M. Levy, a porcelain painter who perceived and valued his precocious skill. Nevertheless his ambition was to become a painter.

From 1860 he copied Old Master paintings in the Louvre, and by 1861 he was a regular visitor to the studio of the painter Charles Gleyre. He was finally admitted to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts on 1 April 1862. Although there are records of his presence at the Ecole until 1864, it is likely that, following the example of the other young artists he had met at Gleyre’s studio, notably Alfred Sisley, Frédéric Bazille and Monet, he was attracted by the practice of painting en plein air in the forest of Fontainebleau. According to Meier-Graefe, he had even been encouraged in this by one of the most famous Barbizon painters, Narcisse Diaz (Meier-Graefe, p. 16).

In 1864 Renoir’s La Esmeralda (untraced, and claimed by the artist to have been destroyed by him), inspired by Victor Hugo’s novel Notre-Dame de Paris (1831), was accepted by the Salon. The following year a very sober work, a portrait of William Sisley (1864; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay), father of his closest friend, Alfred Sisley, was shown in the Salon. Renoir painted many portraits, as much because of his unfailing interest in the face as from financial necessity. Romaine Lacaux (1864; Cleveland, OH, Mus. A.) is typical. However, the work that best characterizes the young Renoir is Cabaret of Mother Antony (1866; Stockholm, Nmus.), which depicts a group of artists in a room in an inn in Marlotte (the ‘annexe’ of Barbizon) conversing around a table and attended by a servant. The subject, the energetic brushmarks, generally sombre tonality and ambitious scale (1.95×1.3 m) of the picture are reminiscent of Gustave Courbet, whose influence continued to dominate Renoir’s Diana the Huntress (1867; Washington, DC, N.G.A.). The Salon jury of 1867 was not deceived by the mythological disguise of this nude, which was obviously a concession by Renoir to the prevailing academic conventions. The work was refused, as were those submitted the same year by Monet and Bazille. They all protested against their exclusion and called unsuccessfully for another Salon des Refusés like that of 1863, in which Manet had shown the Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay). In early 1867 Bazille had rented a studio in the Rue Visconti in Paris, where, during a period of poverty, he put up Monet and Renoir. The influence of Monet, and through him of Manet, is discernible in Renoir’s painting from then on: for example in his portrait of Sisley and his fiancée, the Engaged Couple (c. 1868; Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz-Mus.), and in Lise with a Parasol (1867; Essen, Mus. Flkwang), which depicts Lise Tréhot (1848–1922), Renoir’s mistress and favourite model until 1872. This picture won Renoir his first critical success at the Salon of 1868. Monet’s influence is also seen in several views of Paris (Pont des Arts, c. 1867; Pasadena, CA, Norton Simon Mus.) and in the revealing series of studies (Moscow, Pushkin Mus. F.A.; Stockholm, Nmus.; Winterthur, Samml. Oskar Reinhart) made in 1869, at the same time as Monet, at La Grenouillère, a bathing place on the island of Croissy in the Seine, near Paris. Lise was again the model for In Summer (Berlin, Tiergarten, N.G.), shown in the Salon of 1869, and for two paintings exhibited in the Salon of 1870, Woman Bathing with Griffon (1870; São Paolo, Mus. A.)—another obvious homage to Courbet—and Woman of Algiers (1870; Washington, DC, N.G.A.), a dazzling display of Renoir’s admiration for Delacroix. After the Franco-Prussian war of 1870–71, during which he served in the Tenth Cavalry Regiment, he resumed his links with the artistic world by submitting a work in the same vein to the Salon of 1872, Parisian Women Dressed as Algerians (1872; Tokyo, N. Mus. W.A.), a free interpretation of Delacroix’s Women of Algiers (1834; Paris, Louvre). This picture was refused, as was the huge Riding in the Bois de Boulogne (1873; Hamburg, Ksthalle) in 1873, which he sent to the Salon des Refusés in the same year.

(ii) The Impressionist exhibitions, 1874–8.

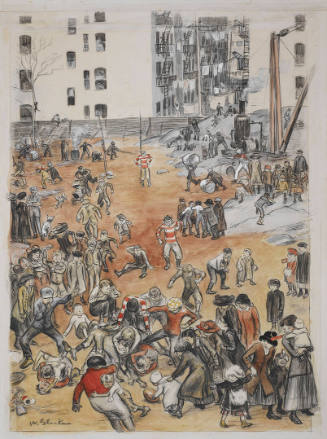

These repeated rejections encouraged Renoir to join a group of fellow artists, headed by Monet, in the First Impressionist Exhibition, which was held in the spring of 1874 at 35 Boulevard des Capucines in Paris. Renoir showed some recent canvases including Dancer (1874; Washington, DC, N.G.A.), Theatre Box (1874; London, Courtauld Inst. Gals) and Parisian Woman (1874; Cardiff, N. Mus.). These were all smaller than his previous paintings, being easier to sell among the very small circle of collectors such as Victor Chocquet, Gustave Caillebotte, Henri Rouart, Jean Dollfus and dealers (including Paul Durand-Ruel) whom he had attracted. The lighter palette he was adopting is most apparent in the landscapes painted at Argenteuil beside Monet (Seine at Argenteuil, 1874; Portland, OR, A. Mus.). At this time he depicted Monet in Monet Working in the Garden at Argenteuil (1874; Hartford, CT, Wadsworth Atheneum). The brushstrokes are also more delicate and expressive in these works, displaying all the freedom of a virtuoso. In comparison with his fellow exhibitors, Renoir had been spared by the critics in 1874, but during the Second Impressionist Exhibition in 1876 he was attacked by the critic of the Figaro, Albert Wolff, who described Study (Nude in the Sunlight) (1875; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay) as a ‘heap of decomposing flesh’—an allusion to the bluish shadows cast on the naked figure by the light of the open air filtering through foliage. Similar interests can be seen in the Ball at the Moulin de la Galette (1876; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay), which he sent to the Third Impressionist Exhibition in 1877. This ambitious composition, depicting a particularly ‘modern’ subject, namely the animated crowd at an open-air dance hall in Montmartre, where the artist was then living, is brought to life by complex effects of light and is without doubt the most perfect example of Renoir’s Impressionism.

(iii) 1879–89.

Renoir refused to be involved in the fourth and fifth Impressionist exhibitions in 1879 and 1880 and indeed returned to the official Salon in 1878. He achieved a great success there in 1879 with the portraits of Mme Charpentier and her Children (1878; New York, Met.) and of the actress Jeanne Samary (1878; St Petersburg, Hermitage). This success was partly due to the celebrity of his models: Mme Georges Charpentier, wife of the publisher of Flaubert, Zola and the Goncourt brothers, applied herself to launching Renoir in fashionable and wealthy circles where buyers were finally found for his portraits (e.g. Irène Cahen d’Anvers, 1880; Zurich, Stift. Samml. Bührle) and other works. This success marked the opening of a new era for Renoir, who was finally freed of more immediate financial constraints. At the end of the summer of 1880, after having exhibited again at the Salon with Young Girl Asleep (1880; Williamstown, MA, Clark A. Inst.) and Women Fishing for Mussels at Berneval, on the Coast of Normandy (1879; Merion, PA, Barnes Found.), he began work on a large composition, Luncheon of the Boating Party (1880–81; Washington, DC, Phillips Col.) at Chatou, near Paris, beside the Seine, on the terrace of the Restaurant Fournaise. The subject recalls both the views of La Grenouillère painted in 1869 and the Ball at the Moulin de la Galette, but comparison with the latter work, painted only four years earlier, reveals a new concern with composition and the distribution of masses, while the drawing is also more meticulous and precise. The faces are clearly individualized; in particular one recognizes on the extreme left Aline Charigot (1859–1915), whom Renoir married in 1890. The picture is painted in a palette of light and vivid tones.

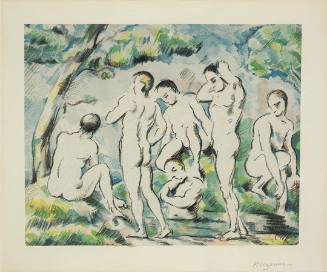

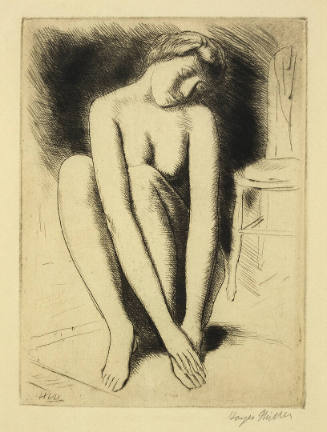

Such works as Bather (1881; Williamstown, MA, Clark A. Inst.), Dance at Bougival (1882–3; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.), Dance in the City and Dance in the Country (both 1882–3; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay), Seated Bather (c. 1883–4; Cambridge, MA, Fogg) and Umbrellas (c. 1881 and c. 1885; London, N.G.) led to Renoir’s ‘Ingresque’ period around 1885 and the incisive and decorative cut-out style of the Bathers (1887; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.). This evolution was doubtless hastened by Renoir’s travels in Italy between 1881 and 1882, from which he returned through the south of France to work beside Paul Cézanne at L’Estaque in January 1882 on such paintings as Rocky Crags at L’Estaque (1882; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.).

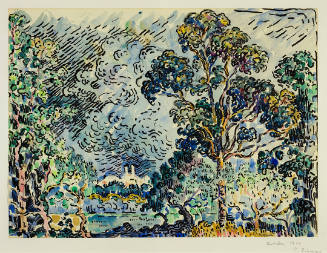

The monumental painting of Raphael and the masterpieces of Classical Antiquity confirmed Renoir’s desire to challenge the subjective uncertainties of Impressionism. He travelled a great deal at the beginning of the 1880s: in the steps of Delacroix, in 1881 and 1882, to North Africa, which he found dazzling and where he painted some splendid landscapes (e.g. Mosque (or Arab Festival ), 1881; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay); and in 1883 to Jersey and Guernsey and then to the Mediterranean coast between Marseille and Genoa in the company of Monet. He exhibited regularly at the Salon (1881, 1882, 1883 and for the last time in 1890) but refused to submit works to the Impressionist exhibitions after 1877, because he felt his presence might alienate his Salon orientated patrons. However, he was unable to prevent Paul Durand-Ruel, the organizer of the 1882 exhibition, from including his paintings. Despite this, he was happy to cooperate when Durand-Ruel put on Renoir’s first individual retrospective exhibition in his gallery in Paris in 1883. Renoir’s adoption of a more linear style was badly received by the critics and by some of the collectors of his work. An exception was Paul Berard, one of his most important supporters, for whom he painted Children’s Afternoon at Wargemont (1884; Berlin, Tiergarten, N.G.).

(iv) The 1890s.

At the end of the 1880s and during the 1890s Renoir often moved around in search of new motifs—Normandy, Brittany, the outskirts of Paris, Essoyes in Champagne (his wife’s village) and Provence. He also visited the great museums in Madrid, Dresden, Amsterdam and London, and this pursuit of the art of the past was reflected in his painting by a gradual return to a more fluid technique, which owed a great deal to French 18th-century painting as well as to Titian, Diego Velázquez and Peter Paul Rubens. An important work of 1892, Young Girls at the Piano (St Petersburg, Hermitage; see also Two Young Girls at the Piano, 1892), is an excellent example of the spirit in which Renoir interpreted a traditional subject. At this time he also did a series of Bathers (1892; New York, Met.; Paris, Mus. Orangerie; Winterthur, Samml. Oskar Reinhart). The birth of his second son, Jean, in 1894, inspired a series of intimate scenes in which the dark-haired Gabrielle Renard, one of Renoir’s favourite models, also appeared (1895–6; priv. col.); and later with Claude (‘Coco’) Renoir, the painter’s third and last son.

(v) 1900 and after.

By the turn of the century Renoir was an established artist. He accepted the Légion d’honneur in 1900. His international standing grew, particularly in the USA, largely due to the unfailing exertions of Durand-Ruel. He was associated with new dealers, notably Ambroise Vollard and the Bernheim brothers and new collectors such as Maurice Gangnat and the Prince de Wagram. After 1902 his health declined progressively and from 1912 he was confined by rheumatism to a wheelchair. His illness led him to prolong his visits to the south of France, and in 1907 he bought the property of Collettes (now a museum) at Cagnes-sur-Mer, where he lived until his death. He worked ceaselessly, trying his hand at sculpture (Venus Victorious, 1914; London, Tate) and painting nudes (e.g. Bathers, 1918–19; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay), portraits (Ambroise Vollard, 1908; London, Courtauld Inst. Gals) and figures in fancy dress (The Concert, c. 1919; Toronto, A.G. Ont.). These were accomplished works whose lyrical colour with its crimson accents was tempered by a classical fullness of form. They suffice to compensate for the mass of weak landscape sketches and still-lifes that have greatly prejudiced a fair assessment of Renoir’s last period.

2. Working methods and technique.

Renoir’s nervous personality was matched by a life-long uncertainty when faced with the technical problems of painting and draughtsmanship, which sprang partly from his lack of a full traditional training. He was never interested in theoretical issues.

He adopted the Impressionist broken brushstrokes in the late 1860s under the influence of Monet in such works as La Grenouillère (1869; Stockholm, Nmus.). In comparison with Monet’s treatment of the same subject (1869; New York, Met.), he concentrated on describing the fashionable costume of the figures in the middle ground with freer and more delicately applied flecks of paint and was more concerned to suggest atmosphere and the effect of sunlight on rippling water than compositional structure or recession.

Renoir’s gradual abandonment of this style in the early 1880s is most clearly apparent in Umbrellas. The right-hand side of the picture seems to have been painted around 1881 in the soft, blurred brushwork characteristic of his manner from the mid-1870s (e.g. Theatre Box). In this area a rich blue predominates with a sparkling surface effect and complex colour mixtures, for instance in the eyes, picked out with liquid highlights, of the little girl. By contrast the right-hand side, painted several years later, is more sombrely handled, with flatter tones and more emphatic and schematized modelling of drapery and faces. The irises of the eyes of the woman in the foreground are represented by flat matt brown discs. It was only in the 1880s that drawing played an important part in his working methods, when he sought through numerous preparatory studies a more considered and linear style and a paler palette for major efforts such as Bathers (1887; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.).

During the 1890s he adopted an increasingly warm palette and more simplified modelling of flesh through graduated tones and a smooth and unfocused brushwork, which culminated in Bathers (c. 1918–19; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay). Renoir emphasized the red tones in this picture, partly in an attempt to compensate for the fading he had observed of the red pigments in his early paintings.

He turned to sculpture only in 1907, and it was not until 1913 that he attempted his first major project, at the suggestion of Vollard, by which time he was too frail to work unaided. For Venus Victorious, Renoir sketched his intentions initially in pencil or oil, from which his assistant Richard Guino produced a small-scale statuette in 1913. Renoir seems to have modelled only the head directly. He then guided Guino with a long stick in making the final adjustments to the monumental enlargement of the figure in 1914. The exact extent of Renoir’s and Guino’s relative contribution to the final result remains uncertain.

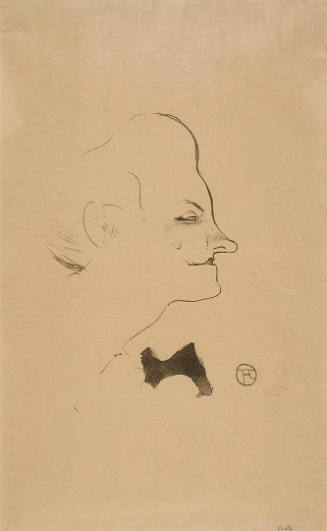

In the 1890s Renoir produced about 50 etchings and lithographs. For his lithograph the Pinned Hat (1898), he reworked on the stone a design transferred from paper and then gave his printer directions in pastel on how it should be coloured. The subject-matter of his prints did not differ from his easel paintings, and the possibilities of the graphic media do not seem to have really engaged his attention.

His younger brother Edmond (1849–1944) became a writer and journalist. He edited the catalogue for the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874, assisted Georges Rivière on L’Impressionniste and organized exhibitions on the premises of the journal La Vie Moderne, for which he also wrote articles. Until the 1880s the brothers were very close: Edmond appears in many of his paintings, including Theatre Box (1874; London, Courtauld Inst.). Their relationship cooled prematurely when Edmond’s zealous support for Auguste’s work led him to criticize the work of the other Impressionists in over-aggressive terms. As a journalist he collaborated on various newspapers, notably La Presse and L’Illustration. [Anne Distel. "Renoir, Auguste." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 10, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T071492.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms

French, 1864 - 1901