Adolph Gottlieb

Adolph Gottlieb

1903 - 1974

American painter and sculptor. He was one of the few members of the New York School born in New York, and he studied at the Art Students League under Robert Henri and John Sloan in 1920–21. He spent the following year travelling through France and Germany and studying at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, Paris. On his return to New York in 1923, he attended the Parsons School of Design and Cooper Union Institute. He was the best travelled of the New York painters (rivalled only by Franz Kline), having been to Paris, Munich and Berlin before even beginning advanced formal studies, and the breadth of his training and art-historical knowledge served him well in his teaching, which was his principal means of support during the mid-1930s. His first one-man exhibition was in 1930, and he showed regularly thereafter as a member of the emerging New York School respected by his contemporaries for his learned and earnest approach to painting.

In 1935, with Mark Rothko, Lee Gatch, William Baziotes and Ilya Bolotowsky among others, Gottlieb founded the Ten, a group that exhibited until 1940. His early paintings of American scenes, such as Sun Deck (1936; College Park, U. MD A.G.), were influenced by the simplified representational idiom of Milton Avery. In 1936 he worked in the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project’s easel painting division and from 1937 to 1939 lived in the Arizona desert. There he painted representational images of cacti and barren scenery; these images gradually metamorphosed into Surrealist-inspired paintings, for example The Sea Chest (1942; New York, Guggenheim), in which mysterious incongruities were injected into otherwise uniform landscapes. Together, these varied experiences informed the grand spaces characteristic of his mature monumental painting. Whereas Pollock had found the Atlantic to be a visual equivalent to the wide open spaces of his native West, ironically Gottlieb, whose hobby was sailing, rejected the insubstantiality of sky and sea and adopted the great western deserts as images of space. This sense of space expressed itself only in his later pictures.

In a letter that Gottlieb and Rothko wrote to the New York Times in June 1943, they (and Barnett Newman in a subsequent letter) laid the theoretical foundations for ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM. ‘We favor the simple expression of the complex thought. We are for the large shape because it has the impact of the unequivocal. We wish to reassert the picture plane. We are for flat forms because they destroy illusion and reveal truth.’ During World War II, the exiled European Surrealists with whom Gottlieb came into contact in New York contributed to his belief that a truly evocative art has its roots in the artist’s subconscious and led him to experiment with essential or archetypal motifs.

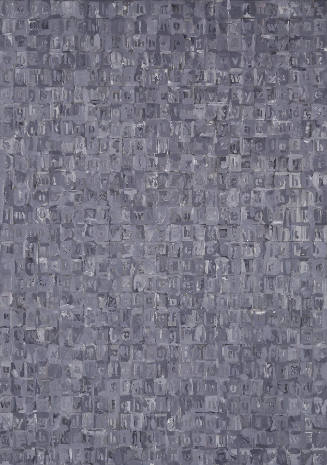

Gottlieb had begun using primitive, timeless images in the Pictographs initiated in 1941 after his return to New York. These paintings, for instance Voyager’s Return (1946; New York, MOMA), in which apparently archaic signs, actually invented symbols, were set into a compartmented surface, reflected his investigations into early cultures, mainly those of North America, but also those of the Ancient Near East. Whenever Gottlieb discovered that one of his signs had an actual precedent in a past culture, he dropped it from his painting vocabulary, thereby rendering his work ‘mute’. This was his gesture towards a universal grammar, or principle of order common to all humanity. Gottlieb hoped that by calling attention to the fundamental properties of language, he would involve spectators in a universal experience.

By the early 1950s his Pictographs had been superseded by a series of Imaginary Landscapes (e.g. Frozen Sounds II, 1952; Buffalo, NY, Albright–Knox A.G.). These works maintained the parallel with written language but also invoked the object-field relationships of deep space. This was not a question of representing a particular landscape, but of suggesting a general sense of foreground and background.

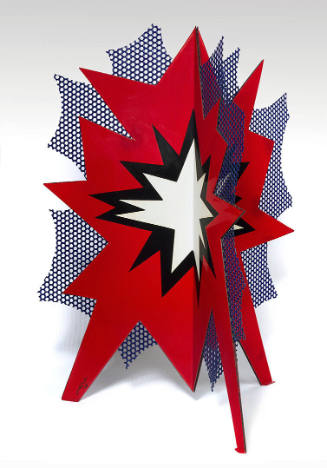

The Burst series that followed presented a radically simplified image. They usually consisted of two shapes, a red disc above a writhing black mass near the bottom of the picture (e.g. Blast I, 1957; New York, MOMA). Together these forms, in various combinations, continued to play out not only the relationship of object to ground in landscape painting, but also an almost theatrical confrontation of two protagonists as in history painting. He experimented with similar shapes in sculptures such as Petaloid (cor-ten steel, 1967; New York, E. Gottlieb priv. col., see H. Geldzahler: New York Painting and Sculpture, 1940–1970, London, 1969, p. 168). Gottlieb distilled the most fundamental relationships out of a complex of sensations re-created with the utmost economy. [(b New York, 14 March 1903; d Easthampton, NY, 4 March 1974).

American painter and sculptor. He was one of the few members of the New York School born in New York, and he studied at the Art Students League under Robert Henri and John Sloan in 1920–21. He spent the following year travelling through France and Germany and studying at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, Paris. On his return to New York in 1923, he attended the Parsons School of Design and Cooper Union Institute. He was the best travelled of the New York painters (rivalled only by Franz Kline), having been to Paris, Munich and Berlin before even beginning advanced formal studies, and the breadth of his training and art-historical knowledge served him well in his teaching, which was his principal means of support during the mid-1930s. His first one-man exhibition was in 1930, and he showed regularly thereafter as a member of the emerging New York School respected by his contemporaries for his learned and earnest approach to painting.

In 1935, with Mark Rothko, Lee Gatch, William Baziotes and Ilya Bolotowsky among others, Gottlieb founded the Ten, a group that exhibited until 1940. His early paintings of American scenes, such as Sun Deck (1936; College Park, U. MD A.G.), were influenced by the simplified representational idiom of Milton Avery. In 1936 he worked in the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project’s easel painting division and from 1937 to 1939 lived in the Arizona desert. There he painted representational images of cacti and barren scenery; these images gradually metamorphosed into Surrealist-inspired paintings, for example The Sea Chest (1942; New York, Guggenheim), in which mysterious incongruities were injected into otherwise uniform landscapes. Together, these varied experiences informed the grand spaces characteristic of his mature monumental painting. Whereas Pollock had found the Atlantic to be a visual equivalent to the wide open spaces of his native West, ironically Gottlieb, whose hobby was sailing, rejected the insubstantiality of sky and sea and adopted the great western deserts as images of space. This sense of space expressed itself only in his later pictures.

In a letter that Gottlieb and Rothko wrote to the New York Times in June 1943, they (and Barnett Newman in a subsequent letter) laid the theoretical foundations for ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM. ‘We favor the simple expression of the complex thought. We are for the large shape because it has the impact of the unequivocal. We wish to reassert the picture plane. We are for flat forms because they destroy illusion and reveal truth.’ During World War II, the exiled European Surrealists with whom Gottlieb came into contact in New York contributed to his belief that a truly evocative art has its roots in the artist’s subconscious and led him to experiment with essential or archetypal motifs.

Gottlieb had begun using primitive, timeless images in the Pictographs initiated in 1941 after his return to New York. These paintings, for instance Voyager’s Return (1946; New York, MOMA), in which apparently archaic signs, actually invented symbols, were set into a compartmented surface, reflected his investigations into early cultures, mainly those of North America, but also those of the Ancient Near East. Whenever Gottlieb discovered that one of his signs had an actual precedent in a past culture, he dropped it from his painting vocabulary, thereby rendering his work ‘mute’. This was his gesture towards a universal grammar, or principle of order common to all humanity. Gottlieb hoped that by calling attention to the fundamental properties of language, he would involve spectators in a universal experience.

By the early 1950s his Pictographs had been superseded by a series of Imaginary Landscapes (e.g. Frozen Sounds II, 1952; Buffalo, NY, Albright–Knox A.G.). These works maintained the parallel with written language but also invoked the object-field relationships of deep space. This was not a question of representing a particular landscape, but of suggesting a general sense of foreground and background.

Adolph Gottlieb: Blast, I, oil on canvas, 2.29×1.15 m, 1957…The Burst series that followed presented a radically simplified image. They usually consisted of two shapes, a red disc above a writhing black mass near the bottom of the picture (e.g. Blast I, 1957; New York, MOMA). Together these forms, in various combinations, continued to play out not only the relationship of object to ground in landscape painting, but also an almost theatrical confrontation of two protagonists as in history painting. He experimented with similar shapes in sculptures such as Petaloid (cor-ten steel, 1967; New York, E. Gottlieb priv. col., see H. Geldzahler: New York Painting and Sculpture, 1940–1970, London, 1969, p. 168). Gottlieb distilled the most fundamental relationships out of a complex of sensations re-created with the utmost economy.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms