David Smith

David Smith

1906 - 1965

American sculptor, painter and draughtsman. Virtually untrained as a sculptor, David Smith liked to say that he ‘belonged’ with painters. His art training began when he moved to New York in 1926 and, on the advice of his future wife, the sculptor Dorothy Dehner (1908–94), he enrolled at the Art Students League (ASL; 1927–32) to study painting and drawing. There he had his first exposure to advanced modernist art. Smith’s early friendship with painters such as Adolph Gottlieb and Milton Avery was reinforced during the Depression of the 1930s, when he participated in the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project in New York. These relationships endured even after the Smiths moved to Bolton Landing, NY, near Lake George, in 1940.

Probably the most significant of Smith’s early connections was with the painter, collector and connoisseur John Graham who provided Smith with information about the latest European art, something in short supply in New York at the time. Through Graham, Smith met Stuart Davis, Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning. Graham also introduced the Smiths to African sculpture and later guided them through Paris on their first European trip, in 1936.

While studying with the Czech-born Cubist painter Jan Matulka (1890–1972) at the ASL, Smith began to make painting-reliefs and eventually three-dimensional works. When Graham showed him photographs of welded metal sculptures by Pablo Picasso and Julio González in the French art magazine Cahiers d’art, Smith realized that the skills he had acquired during summer jobs in a car factory could be used to make art, and in 1933 he made his first welded sculptures, for example the red painted iron and steel Agricola Head (1933; priv. col., see Wilkin, 1984, pl. 12), almost certainly the first to be made in the USA. By the mid-1930s Smith was devoting himself increasingly to sculpture. Before moving upstate, he established a studio at Terminal Iron Works, a welding shop near his Brooklyn home, where he worked alongside commercial welders who offered him technical advice and materials (Smith later gave the name to his Bolton Landing property).

Smith’s early work includes relief plaques such as the bronze Medals for Dishonour (1937–40), bronze and aluminium castings and steel and iron constructions such as Head (1938; New York, MOMA), which incorporate found objects. A single work may consist of several materials, differentiated by varied patinas and polychromy. These small sculptures explored a wide spectrum of formal notions such as figurative expressionism, organic abstraction and geometric construction. Later, Smith’s sculptures became larger, more abstract, and almost exclusively made of steel and found objects, but his approaches remained as diverse, and he remained fascinated by the idea of polychromy, striving (with varying degrees of success) to amalgamate painting and sculpture into a new art form that would, in his words, ‘beat either one’.

Smith sought direction from the European avant-garde. He claimed that his technical liberation came from Julio González, and his aesthetics from Vassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian and Cubism. Smith was clearly indebted to Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Pablo Gargallo and Joan Miró, but he had seen few original sculptures and his notebooks testify to unlikely sources such as Life magazine photographs, pin-up magazine illustrations, fossilized fish and Egyptian tomb furnishings. Smith was inventing a new language of sculpture, drawing upon whatever he could. Despite the initial stimulus provided by the photographs of works by Picasso and González, Smith made his first welded sculptures when such metal constructions had existed for only about five years.

Whatever his sources, Smith’s individuality is obvious in even his earliest works, as evinced by a comparison between the steel and bronze Interior for Exterior (1939; USA, Orin Raphael priv. col., see Marcus, 1983, p. 47), a typical ‘hermetic enclosure’ piece, and a work Smith knew well and clearly admired, Giacometti’s mixed-media sculpture The Palace at 4 a.m. (1932–3; New York, MOMA). The Giacometti is a precariously constructed skeletal structure populated by forms utterly different from their surroundings. Smith appropriated the conception but translated it into his own robust vocabulary, replacing European refinement with ad hoc transformations: Smith’s ‘flying pliers’ parody Giacometti’s frail bird, and Giacometti’s magic toy building becomes Smith’s rigid, irrational metal cage; light, suspended forms become cast and forged masses.

Throughout his career Smith made sculptures that were surprisingly independent of his Cubist influences, his notion of collage being radically different from Cubist prototypes. In Picasso’s constructions and collages, ‘real’ elements were evidence of alien actuality in the invented Cubist world of planes; Smith’s found objects are subsumed by their new settings. He rejected the multiple views typical of Cubist painting, substituting an assembly of varied perceptions and conflating a wealth of pictorial elements into a single structure. His drawings reveal that he habitually took forms from many sources and forced them into new relationships that owed little to their original scale or disposition in space. Smith’s sculptures bring disparate things into unexpected proximity by dispersing them in apparently illogical ways or by compressing them into a single plane. Smith’s imagery is similarly compressed. Throughout his work suggestive, non-specific forms reverberate with layers of allusion, like serious puns. A phallus–gun and a bird–fish–foetus, for example, recur often and in various guises in works such as Spectre Riding the Golden Ass (1945; Detroit, MI, Inst. A.). His wife Dorothy Dehner suggested that this kind of allusive abstraction allowed Smith to make use of intimate emotions without revealing himself fully.

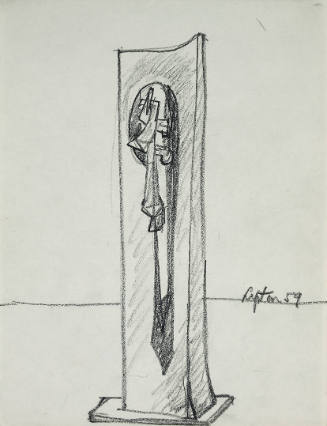

After 1950 when a Guggenheim grant provided some financial security and allowed the purchase of materials in quantity, Smith’s sculpture became larger, more ambitious and less specific, without, however, losing the sense of ‘charged’ imagery present in even his earliest work (e.g. the steel and stainless-steel Hudson River Landscape, 1951; New York, Whitney). After c. 1951 in works such as the red painted steel Running Daughter (1955–60; New York, Whitney) the vertical, upright ‘figure’ became his chief preoccupation, but he continued to use imagery from his early sculpture such as spectres, birds and ambiguous still-life personages. He also retained the habit of elevating his sculptures by the most expedient means possible. His large-scale works dispense with the traditional pedestal. Bases that could be tripods, vertical beams or even wheels are incorporated into the sculpture itself (see fig.). Smith’s mature production challenged preconceptions of what sculpture could be. Slightly larger than human beings, these confrontational, mysterious, open constructions are all edge and elusive planes. Seen from the front, other views of the sculpture can never be predicted. They occupy the viewer’s own space, distancing themselves solely by their degree of otherness from everyday experience. Lectern Sentinel (1961; stainless steel; New York, Whitney) is typical, with its delicately angled planes, its suggestion of both Cubist abstractness and animate presence, and its light-diffusing burnishing.

Mature works such as the steel and bronze Tanktotem II (Sounding) (1952; New York, Met.), the painted steel Zig IV (1961; New York, Lincoln Cent.), the painted steel Circles I, II and III (1962; Washington, DC, N.G.A.) and the steel Voltri IV (1962; Otterlo, Kröller-Müller) were grouped into numbered series. The notion is, however, misleading. Smith worked simultaneously in many different manners encompassing both linear and massive sculptures, which he later assigned to specific groups and numbered. The only exception is the Voltri series, 26 sculptures made in 30 days in Italy during June 1962, when Smith was invited to make work for exhibition at the Festival dei Due Mondi, Spoleto. The Voltri-Bolton series, made subsequently at Bolton Landing, incorporates material from Voltri.

Smith’s working methods were established early. He ran his studio like a factory, stocked with large amounts of raw material. He claimed it was a way of liberating himself, of avoiding being precious with materials. Large sculptures were begun on the floor, steel arranged on a flat, white painted background, then tack-welded and hauled up to be worked in the round. Smith’s industrial technology and materials did not, however, preclude a powerful sense of touch in his work. Subtle manipulations and delicate articulations bear witness to the presence of Smith’s hand and imbue the sculptures with a rich three-dimensionality, usually difficult to decipher in photographs. In Smith’s last, perhaps best-known series, the stainless-steel Cubis of the early 1960s such as Cubi xix (1964; London, Tate), his hand is present in the burnished surfaces, although necessarily excluded from the pre-cut shapes (a concession to his intractable material).

Smith continued to paint and especially to draw throughout his life. By 1953 he was producing between 300 and 400 drawings a year: ‘These drawings are studies for sculpture, sometimes what sculpture is, sometimes what sculpture never can be’ (lecture, 23 March 1953, Portland, OR). His subjects encompassed the figure and landscape, as well as gestural, almost calligraphic marks made with egg yolk, Chinese ink and brushes and, in the late 1950s, the ‘sprays’. The sprays developed from Smith’s sculpture-making process; elements of his work were placed on a white painted floor before welding. The welding often burned the white area giving a negative image of the sculpture. For his sprayed drawings Smith sprayed around objects placed on paper with paint or enamel, sometimes making brushstrokes on unsprayed areas.

From the 1950s Smith received a considerable amount of favourable critical attention, and he was included regularly in prestigious museum exhibitions, yet he sold few works. Only the Cubis, which were among his most accessible pieces, were in demand. He appreciated the continuing support of his lifelong friend, critic Clement Greenberg, by whom his work had been highly praised as early as 1943, before they had met. Other critics often failed to differentiate between Smith and his imitators. Smith’s peers, including the painters of the Abstract Expressionist generation, respected and admired him greatly. The painters Robert Motherwell, Helen Frankenthaler and Kenneth Noland, although younger than Smith, were his close friends and there is evidence of helpful mutual influence. The British sculptor Anthony Caro began to work in steel as a result of seeing Smith’s work on his first visit to the USA in 1959. A generation of British and American sculptors has continued the tradition quite directly, while in a sense the austere geometries of minimal sculpture can be seen as a misinterpretation of Smith’s intentions. Smith was receiving due recognition when he died aged 59 in an automobile accident. [Karen Wilkin. "Smith, David." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 11, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T079293.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms