Mark Rothko

Mark Rothko

1903 - 1970

American painter and draughtsman of Russian birth. He was one of the major figures of ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM and an important influence on the development of COLOUR FIELD PAINTING.

1. Life and work.

In 1913 he immigrated with his mother and sister to the USA, where they were reunited with his father and two older brothers, who had settled in Portland, OR, a few years earlier. As a youth in Portland, Rothko excelled scholastically and in particular pursued interests in literature, music, and social studies. From 1921 to 1923 he attended Yale University on a scholarship, but he left in his third year without graduating. He moved to New York, where he sporadically attended a few courses at the Art Students League, including a painting class with Max Weber, which constituted his only formal training in art. Essentially self-taught, Rothko educated himself by attending exhibitions and visiting the studios of artists such as Milton Avery, whose paintings of simplified forms and flat areas of colour suggested possibilities for Rothko’s own work.

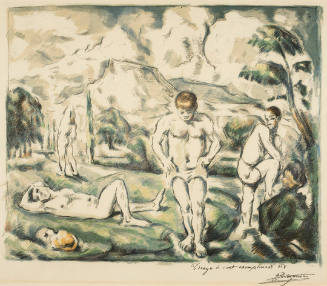

Rothko’s earliest pictures, from the mid- to late 1920s, consist of Expressionist landscapes, genre scenes, still-lifes, and bathers. The paintings, whether on canvas or masonite, tend to be muddy in tone, for example a scene of bathers, Untitled (1930; ex-artist’s col., see 1978 exh. cat., pl. 9). His watercolours of the same period, however, such as the landscape Untitled (late 1920s; ex-artist’s col., see 1978 exh. cat., pl. 3), already demonstrate a masterful handling of thin washes of pigment.

Also among Rothko’s earliest works are the commissioned illustrations for Rabbi Lewis Browne’s The Graphic Bible (New York, 1928). Along with maps of Israel and neighbouring lands are images such as sphinxes, lions, serpents, and the eagle of the Roman Empire, as well as other symbols and scenes reflecting and commenting on the accompanying text. In the course of his research Rothko consulted handbooks on ornament and texts on ancient civilizations and studied the Assyrian collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rothko sued both the author and the publisher of the book for not crediting him as the illustrator and for not paying him his full fee; the transcript of the trial contains his first known statements on art. During the trial he first expressed his lifelong conviction that art was a means for conveying ideas and that his vision of an ideal had to be reconciled with its physical reality.

Most of Rothko’s paintings of the 1930s evoke a sense of mystery and dread. His figures are tragic beings who inhabit claustrophobic apartment rooms or haunt city streets and subway platforms, as in Subway (1930s; Washington, DC, N.G.A.) and Entrance to Subway (1938; Kate Rothko Prizel Collection). Their faces, bathed in unnatural tints of chartreuse, pink, and yellow, contribute to the eerie mood. In 1935 Rothko and other artists who shared a similar sensibility, among them Ilya Bolotowsky and Adolph Gottlieb, formed the Ten, an independent group that mounted exhibitions in New York and Paris until 1940; it was in 1940 that he first used the name Mark Rothko, legally changing it to this form only in 1959. Rothko’s income from the Works Project Administration and from his job teaching children at the Center Academy, Brooklyn Jewish Center, although supplemented by the earnings of his wife, Edith Sachar, a costume jewellery designer, was barely enough for the couple’s subsistence during the Depression. After their divorce at the end of World War II, he married Mary Alice (Mell) Beistel.

In the early 1940s, under the influence of European Surrealism and of Carl Gustav Jung’s theories on the collective unconscious, Rothko abandoned the vestiges of Expressionism in his work and began using archaic symbols as archetypal images transmitting the emotions embedded in ancient myths. Rothko believed in the persistence of basic human impulses enshrined in such myths, and he set himself the task of communicating them as directly as possible without illustrating them. The first of his paintings to be based on mythic subjects contained composite figures of human, animal, and plant forms arranged in a manner resembling archaic friezes. Some of these images were modelled after illustrations in The Graphic Bible or based on the original sources he consulted for this project; from p. 82 of The Graphic Bible, for instance, he adapted the thorns and thistles that appear in Untitled (c. 1942; Purchase, SUNY, Neuberger Mus.).

In place of the recognizable though grotesque figures that populated his paintings on mythical subjects, in his paintings of the mid-1940s Rothko also used organic forms that approached abstraction. In works such as Hierarchical Birds (1944; Washington, DC, N.G.A.) biomorphic shapes seem to float and swirl in front of horizontal zones of colour. Myths, ancient rituals, and the primal state of life continued to be the subjects explored in such paintings as Slow Swirl by the Edge of the Sea (1944; New York, MOMA), Birth of Cephalopods (1944; Washington, DC, N.G.A.), and Vessels of Magic (1946; New York, Brooklyn Mus.).

During the mid-1940s Rothko evolved a personal watercolour technique. Using full supple brushes, in works such as Untitled (c. 1944–6; Washington, DC, N.G.A.), he applied watercolour, gouache, and tempera to heavyweight paper. Before the paint dried, he would use black ink to define forms. When introduced into areas still wet with paint, the ink would bleed, resulting in the black bursts that appear in some of these works. Often Rothko dabbed watercolour in pointillist fashion on to one of the horizontal planes and rubbed charcoal into painted areas, creating velvety opaque passages. He would also scratch and gouge the paper with a sharp implement, exposing the white paper beneath the pigments.

Rothko’s use of watercolour during this period seems to have influenced the technique he developed for his oil paintings (see, for example, Untitled, 1945; Christopher Rothko Collection). In biomorphic works such as Horizontal Vision (1946; Washington, DC, N.G.A.) he began to use oil paint as though it were watercolour, thinning the medium and applying it in overlapping glazes. His paintings of the mid-1940s were generally well received by the press and critics. He exhibited often in New York, at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery, where many of Europe’s avant-garde artists and such American colleagues as Jackson Pollock also showed, and at the Betty Parsons Gallery.

The years 1947 to 1950 were critical to Rothko’s development. In 1946 the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art had organized an exhibition of his oils and watercolours that travelled in reduced form to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, California. In summer 1947 and again in 1949 he taught at the California School of Fine Art, San Francisco, where he worked closely with Clyfford Still. Around this time he stopped making direct reference to the human figure, as his purpose was to present not specific individuals but the universal human drama. To these ends Rothko sought to dispense with his previous influences and to devise a highly original approach to abstraction. The first paintings in which he eliminated the figure consist of amorphous masses of colour that spread across the entire surface of the canvas, as in Number 18 (1947; Washington, DC, N.G.A.). He devised an even more radical solution in Untitled (1949; New York, Met.) and other paintings of the same year by simplifying the forms to create paintings of soft luminous rectangles that appear to float on a stained field. As a result of the shimmering and flickering light and the pulsating colours that project and recede, Rothko’s large canvases produce an impression of constant motion. The intense colour and bold form merge into a single unified image whose impact transcends the sum of its individual components (see, for example, Red and Orange, 1955; New York, MOMA).

Rothko felt the subject-matter of his new paintings to be consistent with that of his earlier work, stressing that he had not removed the human figure but that he had simply put symbols—and later, shapes—in its place. In his view, paintings such as Ochre and Red on Red (1954; Washington, DC, Phillips Col.) were neither arrangements of flat geometric forms, as in Mondrian’s paintings, nor vast landscapes or atmospheric backdrops. Instead he thought of his rectangular forms as actual objects positioned over the field of background colour. Having always emphasized the pre-eminence of subject-matter over form in his work, he felt the evolution of his classic paintings, such as Red, Brown and Black (1958; New York, MOMA) and No. 13 (White, Red on Yellow) (1958; New York, Met.), to have resulted from a desire to express profound human emotions as directly as possible. As he stated in Tiger’s Eye in 1949: ‘The progression of a painter’s work…will be toward clarity; toward the elimination of all obstacles between the painter and the idea, and between the idea and the observer.’ Motivated by a belief in art as a form of language, he explained in an interview in 1957 with Selden Rodman: ‘I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom…and if you…are moved only by their color relationships, then you miss the point.’

Rothko insisted on controlling the way his works were exhibited, as he believed that an insensitive installation could affect his intentions and make the paintings appear decorative. The optimal viewing conditions, in his opinion, involved groups of paintings that filled an entire room to create a dramatic and intimate environment. He disliked his paintings being displayed individually or with works by other artists and felt that lighting should always be indirect. In 1958 he received the first of three major commissions, which offered him the opportunity to create related groups of paintings that would be installed in ensembles. On completion of this first group of paintings in 1959, intended for the Four Seasons Restaurant in the new Seagram Building in New York (designed by Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson), he decided that the location was inappropriate and withdrew from the commission. They were originally meant to hang edge-to-edge as a continuous frieze, with the large narrow panels installed above a series of doors in the room. Nine of these paintings, each conceived as a single rectangle or a pair of open rectangles on a dark field and titled Red on Maroon or Black on Maroon, were eventually bequeathed by him to the Tate, London.

When Harvard University commissioned Rothko in 1961 to paint murals for the penthouse of the Holyoke Center, he conceived a plan similar to the Seagram series, painting a monumental triptych and two additional canvases for the facing walls. The paintings were hung high off the floor, just above the chairs in the room, and the triptych stretched almost from wall to wall. The third major commission, which followed in 1964, was for an octagonal chapel being built in Houston, TX, for John and Dominique de Menil. Rothko’s dark and meditative paintings (1965–6) included a triptych for the apse and four panels for the diagonal facing walls, all painted entirely with black and violet washes. The two additional triptychs on the side walls and the panel on the entrance wall opposite the apse consist of a single black, hard-edged rectangle on a maroon field.

Beginning with the Seagram murals, Rothko deepened his palette, favouring maroon, black, and olive green (see, for example, No. 14, 1963; Paris, Pompidou). He believed that these darker colours conveyed a sense of the tragic more immediately than the bright paintings of the 1950s, and he stressed their dependence not on his own moods but on a desire to communicate more comprehensively his view of the human condition. Nevertheless he was left physically weakened and depressed by an aneurysm of the aorta in May 1968. For many months afterwards he found it difficult to paint large canvases and turned almost exclusively to small and brightly coloured paintings on paper. During this period he also undertook a major inventory of the hundreds of works he still owned, many of them dating from the beginning of his career and including about 1200 sketches and studies; as most of these were unsigned and undated, he now signed and dated each piece as it was inventoried.

In summer 1968 Rothko began his last major series of paintings on paper and canvas; each was divided into two horizontal areas, the top section painted brown or black and the lower part grey. The two regions extend to the narrow white band at the painting’s edges, as in Untitled (acrylic on paper, 1968; London, Tate). Unlike his earlier paintings in which the rectangles seem to float above the field, the white edge of these works immobilizes the brown and grey areas. In both subject-matter and composition the tragedy of man’s isolation conveyed by these desolate paintings bears close comparison with Untitled (1930s; Washington, DC, N.G.A.), an early figurative work by Rothko of an old man sitting alone in a room. Simultaneously with the brown and grey paintings, Rothko produced a series of large, vibrantly coloured paintings on paper. In some of these works velvety black and dark bottle green rectangles nearly eclipse radiant blue fields, while in others, such as Untitled (1969; Washington, DC, N.G.A.), the fusion of brilliant oranges and yellows exudes an unearthly glow and a force not experienced in his earlier brightly coloured works. The circumstances of Rothko’s death by suicide have led to his late works being interpreted as a reflection of his depressed state, but until the end of his life Rothko continued to maintain that his work was not a form of self-expression but a means of communicating his ideas about the condition of mankind. [Bonnie Clearwater. "Rothko, Mark." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 11, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T074108.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms