Louise Nevelson

Louise Nevelson

1899 - 1988

American sculptor, draughtswoman and printmaker of Ukrainian birth. She grew up in Rockland, ME, having moved there with her family three years after her father had settled in the city, where he operated a lumberyard. Shortly after her marriage to Charles Nevelson in 1920, she moved with her husband to New York and began to educate herself as an actress, pianist, dancer, singer and painter while preparing for a career as a sculptor. Among her surviving early works are pen-and-ink drawings representing the human figure in a fluid outline, such as Untitled (1930; New York, Whitney). From 1928 to 1930 she studied at the Art Students League in New York under Kenneth Hayes Miller and Kimon Nicolaides, and after separating from her husband she travelled in 1931 to Munich to study briefly at the Hofmann Schule für Moderne Kunst run by Hans Hofmann until he was forced by the political situation to emigrate to the USA. Nevelson remained in Europe, working as an extra in films in Berlin and Vienna, before returning to her studies with Hofmann at the Art Students League, where he had re-established himself as a teacher in 1932. Through Hofmann she became aware of Cubism and techniques of collage, which affected her development as an artist. Cubism and Surrealism, along with African, American Indian and Pre-Columbian art, were paramount influences on the works she exhibited in group shows in the 1930s, such as Self-portrait (1938; ex-artist’s col., see Glimcher, p. 55).

In 1933 Nevelson and others assisted Diego Rivera in the preparation of his Portrait of America murals for the Communist Party Opposition at the New Workers School on 14th Street, a work that aroused controversy because of its socialist viewpoint; in 1937 she was employed by the Works Progress Administration as a teacher at the Educational Alliance School of Art in lower Manhattan. Nevertheless she remained practically unknown as an artist until 1941, when she persuaded Karl Nierendorf to offer her a one-woman show at the Nierendorf Gallery in New York. There she displayed an environment with overtones of a prehistoric cave, an Egyptian tomb and a well-designed store window, conjuring a real or imagined world or perhaps a vanished and unpopulated one. A year later she created The Circus, Menagerie Animal and a related group of small wood assemblages (destr., see Glimcher, pp. 48–9) in which she used found objects for the first time, laying the basis for her mature style. These were followed by other assemblages in wood, such as Ancient City (1945; Birmingham, AL, Mus. A.), and works made of terracotta, such as Moving—Static—Moving—Figures (c. 1947; New York, Whitney).

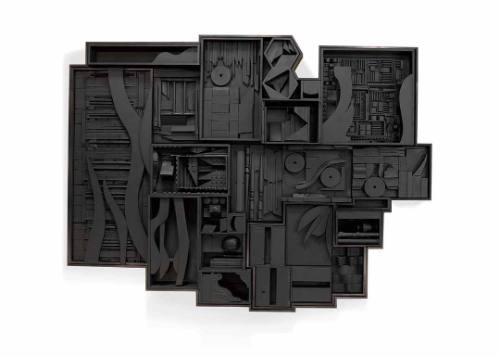

In 1947 Nevelson worked at Stanley William Hayter’s printmaking workshop, Atelier 17, where she began to etch; her first technically inventive aquatints, however, such as Flower Queen (see Glimcher, p. 62), date from 1953. The greatest strides in her work resulted in a one-woman exhibition in 1958 at the Grand Central Moderns Gallery, New York, which featured a distinctive environment entitled Moon Garden Plus One (see Glimcher, pp. 80–83) and Sky Cathedral (1958; New York, MOMA), a room-size sculpture of stacked boxes filled with fragments of carved wood and found objects such as chair backs, finials, furniture legs, mouldings, spindles, and bits of architectural ornamentation. This was one of the earliest of her large-scale reliefs to occupy an entire wall. By gathering together fragments into a complex assemblage painted black to obscure the original identity of the elements and unify them formally, she succeeded in transforming mundane bric-à-brac into enchanting and mysterious structures resembling walls and columns, bringing into play elements from Cubism, action painting and colour field painting.

These all-black pieces were succeeded by all-white assemblages such as Dawn’s Wedding Chapel (1959; New York, Whitney; see fig.) and by all-gold environments such as An American Tribute to the British People (1960–65; London, Tate). Later she made sculptures in clear perspex, for example Transparent Sculpture II (1967–8; New York, Whitney), and metal sculptures, such as Atmosphere and Environment I (aluminium and black epoxy enamel, 1966; New York, MOMA), all of which contributed to the substantial reputation she acquired during the 1960s. Her sculptures became more geometric, open and systematic, and her use of durable materials such as Cor-Ten steel made possible, in 1969, her first outdoor sculpture commission from Princeton University in Princeton, NJ, which was followed by many other public commissions such as Transparent Horizon (1973; Cambridge, MA, MIT). In 1971 she began to fabricate free-standing constructed steel sculptures based on botanical shapes that suggested gardens, landscapes and primordial images, for example Seventh Decade Garden I (direct-welded painted aluminium, 1971; Basle, Gal. Beyeler); see also Untitled, 1972-3. One of the outstanding achievements in her prolific production was Louise Nevelson Plaza, completed in 1979, an outdoor environment of seven sculptures in New York’s financial district. She received many honours including the Gold Medal Sculpture from the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1983, the National Medal of the Arts in 1985, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s Great Artist Series Award in 1986. [Martin H. Bush. "Nevelson, Louise." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 9, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T062080.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms