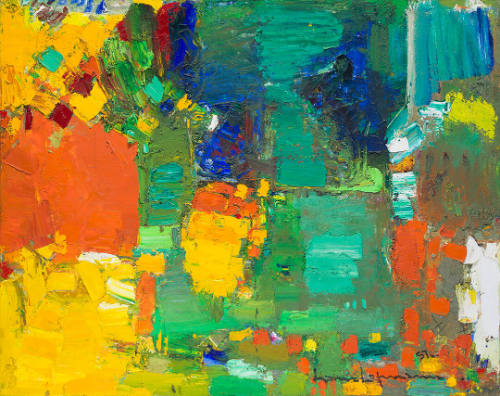

Hans Hofmann

Hans Hofmann

1880 - 1966

American painter, teacher and theorist of German birth. He moved with his family to Munich in 1886 and in 1896 left home to become assistant to the director of public works of the State of Bavaria; he distinguished himself with a number of inventions, including an electromagnetic comptometer, a radar device for ships, a sensitized light bulb and a portable freezer unit for military purposes. In spite of his parents’ strong objection and their hopes for his career as a scientist, in 1898 he enrolled in the art school run by Moritz Heymann (b 1870) in Munich. Hofmann subsequently studied with a succession of teachers and was particularly influenced by Willi Schwarz (b 1889), who familiarized him with French Impressionism, a style that affected his earliest known paintings, such as Self-portrait (1902; New York, Emmerich Gal., see Goodman, 1986, p. 14).

In 1903 Hofmann was introduced by Schwarz to Phillip Freudenberg, an art collector and the son of a wealthy owner of a department-store from Berlin. Freudenberg’s patronage enabled Hofmann to live in Paris from 1904 to 1914, accompanied by Miz (Maria) Wolfgegg, whom he had met in 1900 and whom he married in 1929. Hofmann continued his art studies in Paris at the Académie Colarossi and at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, and he met major artists such as Picasso, Matisse, Braque, Léger and Robert Delaunay; he also came to know the influential German art dealers Richard Goetz and Wilhelm Uhde and the American collector Leo Stein. He also maintained his contacts in Germany, which he visited each summer, participating in the Neue Sezession exhibitions in Berlin in 1908 and 1909 and holding his first one-man exhibition in 1910 at Paul Cassirer’s gallery in Berlin.

Almost all the work produced by Hofmann in Paris was destroyed in World War I. He was visiting Germany when war was declared and was unable to return to France, but for health reasons he was pronounced unfit for service. To support himself he opened his own art school in 1915, the Hofmann Schule für Moderne Kunst, in Schwabing, the artists’ district of Munich. He had relatively few pupils during the war, but as his fame spread after 1918 he attracted students from all over the world; among them were a number of artists who later achieved international prominence, including Alfred Jensen, Louise Nevelson and Wolfgang Paalen. Hofmann taught in Munich until the early 1930s and during these years drew copiously but had little time to paint. Only one painting of this time is known to have survived, a Cubist-derived still-life, Green Bottle (1921; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.).

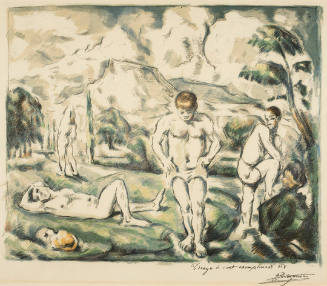

Hofmann visited the USA in the summers of 1930 and 1931 to teach at the University of California at Berkeley at the invitation of a former student, Worth Ryder. In 1932 he settled in New York, where he taught at the Art Students League and where thanks to his first-hand experience of Europe he came to personify the Ecole de Paris for those students eager to learn the fundamentals of modern art. In autumn 1933 he left the Art Students League to open his own school, the Hans Hofmann School of Fine Arts, which after several moves was based at 52 W. 8th Street in the Greenwich Village area of New York. In 1935 he opened a summer school in Provincetown, MA, which became the focus of the large art community on Cape Cod. It was during this period that Hofmann began painting regularly again, initially favouring portraits and figure studies, landscapes, interiors and still-lifes; the strongest influence on his works of this period, such as Japanese Girl (1935) and Table with Fruit and Coffee-pot (1936; both Berkeley, U. CA, A. Mus.), was that of Matisse.

In the 1930s and 1940s Hofmann played an increasingly prominent role in American art, particularly in transmitting modernist theories and new artistic developments. He taught many younger artists who later became established figures, including Lee Krasner, Helen Frankenthaler and Larry Rivers, and he continued teaching throughout the year until 1958, when he finally closed his schools and devoted all his time to painting. The importance of his own art was for a long time overshadowed by his immense influence as a teacher and theorist, but by the late 1950s he was beginning to be recognized as one of the major figures of ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM. Like other artists of his generation in the USA, in the early 1940s he became interested in procedures of automatism derived from Surrealism, in his case less as a way of using the subconscious than as a technique for creating new forms. In works such as The Wind (oil, duco, gouache and India ink on poster board, ?1942; Berkeley, U. CA, A. Mus.) he produced some of the earliest examples of drip painting; although the dating of these works is open to question, they may have preceded the exploitation of similar techniques by Jackson Pollock, to whom Hofmann was introduced by Lee Krasner in 1942.

In spite of an initial hostility between Hofmann and Pollock, a close friendship evolved between them, which affected them both as artists. The imagery and techniques of Pollock’s mythological paintings such as Moon-Woman Cuts the Circle (1942; Venice, Guggenheim), for example, were directly reflected in paintings by Hofmann such as Idolatress I (1944; Berkeley, U. CA, A. Mus.). Within a few years, however, Hofmann had developed a highly distinctive form of abstraction based on patches of vivid colour, vigorous gestures and textural contrasts, as in The Third Hand (1947; Berkeley, U. CA, A. Mus.). Although the dense surfaces and impulsive application of paint in his works of the 1950s, such as Le Gilotin (1953; Berkeley, U. CA, A. Mus.) and Fantasia in Blue (1954; New York, Whitney), can be associated with action painting, it soon became apparent that his work was distinguished by a rigorous concern with pictorial structure, spatial illusion and colour relationships. He is most admired for his late paintings such as Magnum Opus (1962; Berkeley, U. CA, A. Mus.), in which he placed rectangles of single colours against more loosely painted backgrounds to establish dynamic pictorial relationships as well as a strong surface design. His influence among younger abstract artists, such as Helen Frankenthaler and the English painter John Hoyland, remained undiminished long after his death. [Cynthia Goodman. "Hofmann, Hans." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 8, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T038483.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms