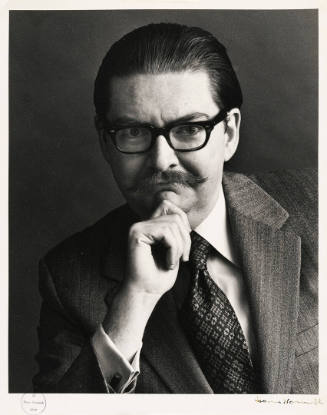

Joseph Cornell

Joseph Cornell

1903 - 1972

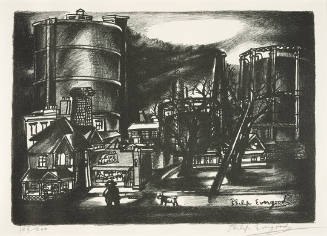

American sculptor, film maker and writer. Cornell studied from 1917 to 1921 at Phillips Academy in Andover, MA. After leaving the Academy he took a job as a textile salesman for the William Whitman Company in New York, which he retained until 1931. During this time his interest in the arts developed greatly. Through art reviews and exhibitions he became acquainted with late 19th-century and contemporary art; he particularly admired the work of ODILON REDON. He also saw the exhibitions of American art organized by ALFRED STIEGLITZ and became interested in Japanese art, especially that of ANDŌ HIROSHIGE and KATSUSHIKA HOKUSAI. Following a ‘healing experience’ in 1925 he became a convert to Christian Science.

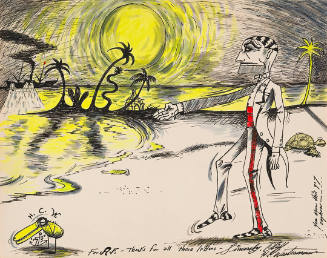

In 1931 Cornell lost his job as a salesman. In November 1931 he discovered Julien Levy’s newly opened gallery in New York and showed Levy some of his collages. Employing curious juxtapositions, these were composed from cut-out fragments of engravings as in Untitled (1931; artist’s estate, see 1980–81 exh. cat., pl. 5). They closely resembled the collages of MAX ERNST, which Cornell had seen at Levy’s gallery, although he had probably been experimenting with collage before this. Through Levy, Cornell became acquainted with a wide range of Surrealist art as well as with various artists in New York, including Marcel Duchamp, whom he first met in 1934. In January 1932 he was included in the Surrealism exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery, the first survey of Surrealism in New York, to which he contributed a number of collages and an object. By the time of his first one-man show at the same gallery in November 1932 he had begun producing his shadow boxes. These were small circular or rectangular found boxes containing mounted or unmounted engravings and objects. At the same show, which was concurrent with an exhibition of engravings by Picasso, Cornell displayed Jouets surréalistes and Glass Bells. The former (c. 1932; Washington, DC, N. Mus. Amer. A.) were small mechanical and other toys altered by the addition of collage, this use of toys suggesting the relationship between art and play. The Glass Bells contained assemblages of collage and other objects.

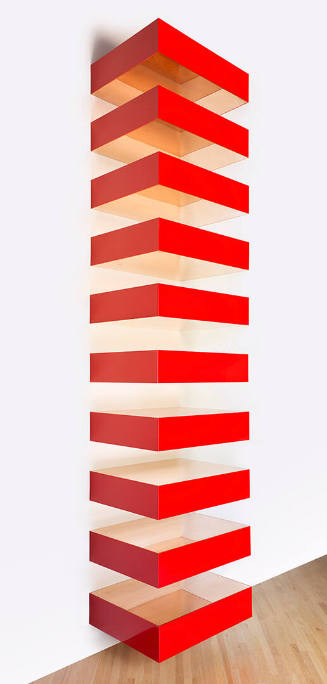

From 1932 to 1935 Cornell learnt woodworking techniques from a neighbour in order to custom-build the wooden boxes for his assemblages, and from 1936 this became his preferred method, although he still occasionally used found boxes. Having been largely unemployed since 1931, c. 1934 he found a job through his mother’s friend Ethel Traphagen designing textiles for the Traphagen Commercial Textile Studio in New York; he continued working there until 1940. He made his first film, Rose Hobart, c. 1939, which was essentially a drastically re-edited version of a film called East of Borneo (1931) in which Rose Hobart had starred. By incorporating sudden incongruous transitions from one scene to another and breaking up the original narrative sequence, Cornell effected a startling transformation of the undistinguished original. He screened the film without any soundtrack in December 1936, and it was shown officially in 1939 at the Julien Levy Gallery.

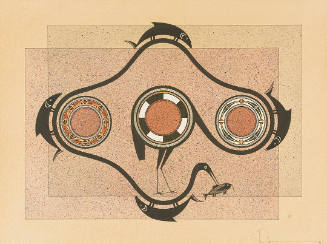

The earliest of Cornell’s hand-made box assemblages is Untitled (Soap Bubble Set) (1936), which formed part of a larger installation at the Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism exhibition organized by Alfred H. Barr jr, at MOMA, New York. The work incorporates the hallmarks of much of Cornell’s work: a series of compartments containing objects together with arcane engraved images, the whole work being unified by various conceptual and visual associations. The objects in this box include four cylindrical weights, an egg in a wine glass, a cast of a child’s head, a clay pipe and a map of the moon. The clay pipe, with which soap bubbles can be made, has a clear relationship to childhood and hence the child’s head. For Cornell the soap bubble also symbolized the contemplation of the cosmos as suggested by the lunar map. Visual associations are presented by the circular forms of the egg, the moon, the implied soap bubbles and even the child’s head. Such associative networks clearly bear an affinity with Surrealist art, and this was reflected by the discussion of his works in this context in much contemporary criticism. Despite sharing the Surrealists’ similar literary tastes for such 19th-century writers as Arthur Rimbaud and Gérard de Nerval, Cornell did not have their interest in psychology and the subconscious. Before the exhibition at MOMA (1936) he wrote to Barr in an attempt to distance himself from mainstream Surrealism. Cornell was furthermore unconcerned with the erotic themes favoured by the Surrealists and it seems therefore that the French movement acted more as a catalyst in Cornell’s development rather than as a rigid framework.

After finishing his work for Traphagen’s in 1940, Cornell was able to devote himself more fully to his art, although he also undertook freelance work producing illustrations and designing layouts for magazines such as Vogue and House and Garden until 1957. In the 1940s he paid more serious attention to his writing, which had earlier appeared only in notes and correspondence. From 1941 to 1947 he contributed articles to View and Dance Index. Concentrating largely on his box works, in the 1940s Cornell tended to work in thematic series. He made further Soap Bubble Set boxes and created series such as Pharmacy that extended into the 1950s. Untitled (Pharmacy) (c. 1942; Venice, Guggenheim), for example, is characteristic of these, consisting of a shallow box lined with rows of small glass drug bottles, each filled with an assortment of materials and objects. Birds were recurring motifs, particularly parrots, cockatoos and owls, which appeared in a number of boxes throughout the 1940s (e.g. Untitled, c. 1940s). Some used stuffed birds, for example Parrot Music Box (c. 1945; Venice, Guggenheim), in which the parrot is claustrophobically enclosed in an overtly alien environment in a parody of the bird and animal cases of the 19th century. In Untitled (Owl Box) (1945–6; Paris, Pompidou) Cornell incorporated a cut-out owl into a near ‘natural’ woodland habitat, relying on the traditional variety of the bird’s connotations for the work’s suggestive effect: the owl as a premonition of death, Devil’s accomplice, embodiment of wisdom and so on. From the late 1940s and into the 1950s he also produced a number of austere white abstract boxes inspired by Mondrian’s work, such as Untitled (Window Façade) (c. 1953; New York, priv. col., see 1980–81 exh. cat., pl. 223), the top of which is covered by a rectolinear network of white, wooden strips.

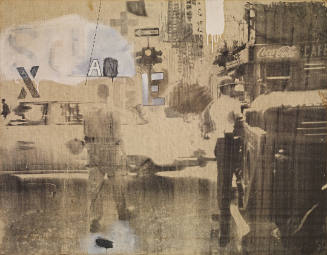

In the 1950s Cornell resumed his film-making but this time in the role of director and editor of original rather than found footage, using such cameramen as Rudy Burckhardt and Stan Brakhage. This led to several short films in both black and white and colour, such as GniR RednoW (1955), filmed by Brakhage, and Nymphlight (1957), filmed by Burckhardt. From 1955 Cornell again started to produce collages as an independent medium, producing works such as Allegory of Innocence (c. 1956; New York, MOMA). Many of his boxes of the mid to late 1950s included references to the constellations, as in Untitled (Space Object Box) (c. 1958; New York, Guggenheim), though this theme had appeared earlier as well. Due to declining health and the grief caused by the death of his brother and mother, from the 1960s Cornell produced few boxes, although he continued to make collages such as Sorrows of Young Werther (1966; Washington, DC, Hirshhorn). [Philip Cooper. "Cornell, Joseph." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 4, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T019548.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms