Thomas Eakins

Thomas Eakins

1844 - 1916

American painter, sculptor and photographer. He was a portrait painter who chose most of his sitters and represented them in powerful but often unflattering physical and psychological terms. Although unsuccessful throughout much of his career, since the 1930s he has been regarded as one of the greatest American painters of his era.

1. Life and work.

His father Benjamin Eakins (1818–99), the son of a Scottish–Irish immigrant weaver, was a writing master and amateur artist who encouraged Thomas Eakins’s developing talent. Eakins attended the Central High School in Philadelphia, which stressed skills in drawing as well as a democratic respect for disciplined achievement. He developed an interest in human anatomy and began visiting anatomical clinics. After studying from 1862 at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where instruction was minimal, Eakins went to Paris to enrol at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, in the studio of JEAN-LÉON GÉRÔME. From 1866 to the end of 1869 he worked intensely under Gérôme, supplementing his artistic studies with dissection and also briefly studying under the sculptor AUGUSTIN-ALEXANDRE DUMONT and the portrait painter LÉON BONNAT. He completed his tour of Europe with six months in Spain, the high-point of which was his study of Velázquez at the Museo del Prado, Madrid. When he returned to settle in Philadelphia in July 1870, he had determined that he would make portrait painting his life’s work and that, despite his training in the closely detailed style of Gérôme, he would cultivate the broad brushwork and indirect painting techniques of Velázquez. Assured of his father’s financial support, he embarked on a career of painting portraits of eminent men and women, mostly from Philadelphia. Although he ultimately painted just under 300 works, he received commissions for only about 25.

Max Schmitt in a Single Scull, painted at the start of his career, was the first of a number of paintings and watercolours in which Eakins honoured champion rowers. Rowing had recently become popular, celebrated for its demands on physical and mental discipline, and its experts were widely admired. Eakins portrayed his subject—a friend from boyhood—resting on the oars during an afternoon’s sculling on Philadelphia’s Schuylkill River. Evidence of Schmitt’s triumph in the city’s first amateur single sculling race is scattered throughout the painting: specific bridges identifying the race-course, rowers in the middle distance wearing Quaker garb, and the name on Schmitt’s racing shell. Eakins himself appears in the scene, sculling in the middle distance. Stylistically, the painting combines exactitude in the boats and bridges with sketchy, generalizing forms in the foliage and sky. During the 1870s Eakins also painted hunting scenes, such as Will Schuster and Blackman Going Shooting for Rail (1876; New Haven, CT, Yale U. A.G.) and Pushing for Rail (1874; New York, Met.), as well as portraits of his sisters (e.g. Frances Eakins, 1870; Kansas City, MO, Nelson–Atkins Mus. A.) and other young women at the piano or in other interior pursuits.

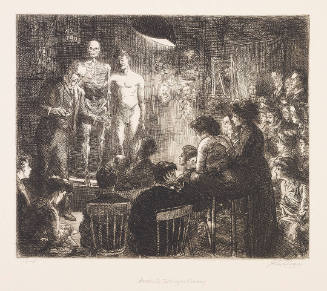

In 1875, inspired by the approaching Centennial exhibition for which artists were urged to paint national subjects, Eakins painted the Gross Clinic. It was the largest and most complex figural composition he had undertaken. Calling the work ‘Portrait of Professor Gross’, Eakins portrayed the internationally renowned Philadelphia surgeon Dr Samuel Gross, shown presiding over an operation in the surgical amphitheatre at Jefferson Medical College. Several other surgeons assist Gross, medical students look on from the tiers of the amphitheatre, and Eakins himself sketches the scene from front left. Gross lectures, holding in his hand a scalpel covered with blood. Painted in a range of dark tones illuminated by brilliant light on Gross’s forehead, hand and on the patient, the work shocked the Centennial jury. While it had obvious precedents in Rembrandt’s paintings of anatomy lessons and in 19th-century group portraits of French surgeons preparing for dissection, such as Auguste Feyen-Perrin’s Anatomy Lesson of Dr Velpeau (1864; Tours, Mus. B.-A.), Eakins had broken new ground by painting an actual operation in progress, with instruments and blood in full view. With the specific details of his painting, he paid tribute to the advances of American surgery and to the particular role that Gross had played in them. The jury rejected the painting, but Gross sponsored its exhibition in one of the medical exhibits. Eakins was to return to such a powerful theme only once. In 1889 the graduating class of the University of Pennsylvania Medical School asked him to paint a portrait of their retiring professor of surgery, Dr D. Hayes Agnew. Instead, in the Agnew Clinic (1889; Philadelphia, U. PA), Eakins insisted on painting a surgical clinic, presided over by Agnew, in which all the advances of surgery since the portrait of Gross are displayed: the use of antiseptic, white operating clothing, sterilization of instruments and a nurse in an operation for breast cancer.

Despite the critical dismay over the Gross Clinic, Eakins gained respect as a teacher at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, becoming its director of instruction in 1882. Drawing on his own experience as a student as well as on his temperament as an artist, he devised a thorough, professional curriculum, at the heart of which was the study of the human figure. Eakins was adamant that the Academy facilities were primarily for professional artists rather than artisans or amateurs. The Board of Directors of the Academy, none of them artists, wanted the programme to be self-sustaining and thus to attract students of all capabilities. In 1886 the Board forced Eakins’s resignation, nominally over a dispute about the use of a nude male model in a mixed drawing class: the action deeply hurt him. Although he did teach sporadically at other institutions, he missed the authority the Academy position had given him in Philadelphia’s professional community.

The nature of Eakins’s portraiture changed after this period. His disappointment at the Academy may have been underlined by the mixed reception that his earlier complex portraits had received and by the personal stress caused by the death of several members of his family. He was sustained emotionally by the artist Susan Hannah Macdowell (1851–1938), a sympathetic companion whom he had married in 1884. After the forced resignation, he travelled to the Dakota Territory in late 1886 for a ‘rest cure’. Shortly afterwards he met the poet Walt Whitman (1819–92). They developed a friendship, made more intense by their common experience of having their work misunderstood. Eakins’s portrait of Whitman (1887; Philadelphia, PA Acad. F.A.)—like many of his later works, a bust-length view—shows him tired and aging. Over the next two decades some of his most sensitive portraits in this format were of women (see fig.). The subjects seem to be isolated and grieving, yet of great emotional strength. One such picture is Mrs Edith Mahon (1904; Northampton, MA, Smith Coll. Mus. A.).

Eakins also painted a number of large, full-length portraits in which accessories and background, if present at all, are set apart from the lone figure. As in earlier works, he continued to choose sitters whose achievements impressed him. Physicians, scientists, anthropologists, members of the Catholic hierarchy and musicians came to his studio at his request to be painted. The Concert Singer (1892; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.) combines many of the methods he used during these years. The singer stands alone on a stage that is only hinted at, giving herself completely to the performance of her music. Both her posture and the fragile colouring of the work convey a deep-seated melancholy.

In the last working decade of his life, between 1900 and 1910, Eakins enjoyed some critical appreciation (see fig.). He won several prizes, one in Philadelphia (1904) and others at international expositions in Buffalo (1901) and St Louis (1904), and he served on the art jury of the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh. The memorial exhibitions in New York and Philadelphia in 1917 and 1918 led to the enthusiastic appreciation of his art that continues today. Many of the works in those exhibitions came from Eakins’s studio, having been rejected by sitters, and now form the core of the major repository of Eakins’s work, the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

In comparison to his contemporaries John Singer Sargent and William Merritt Chase, Eakins was technically conservative, resolutely local and non-aristocratic. He had no direct followers among students. It is not clear whether he realized that, especially in his later work, he subverted the traditional role of the portrait as a conveyor of power and grace. He told an admirer that he considered all his sitters ‘beautiful’ and yet wrote to a student that the mission of the painter was to ‘peer deeply into American life’.

2. Working methods and technique.

Although Eakins is traditionally called a ‘scientific realist’, the implications of the term must be tempered in understanding his work. He had an intelligence that demanded precise physical knowledge of his subject, and no other American artist had such a wide range of technical knowledge and skills—several types of perspective, human and equine anatomical dissection, mathematics, the mechanics of stop-motion photography, sculpting and even woodworking. However, he made it clear to his students and to interviewers that these skills were subservient to the goal of art, the creation of beauty.

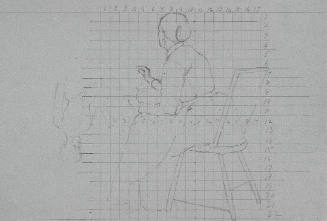

Early in his career Eakins generally made drawings in preparation for paintings. Extraordinarily detailed studies for one of the boat paintings (the Pair-Oared Shell, 1872; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.) include precise calculations for the movement of the surface of individual waves of water as well as the fall of light. Yet he apparently abandoned drawing as a preparation as early as the mid-1870s, and, except for works of his youth, no independent drawings are known. His normal preparation for a portrait consisted of a very small oil sketch on cardboard, squared up, and then a larger oil study to set tonal and colour relationships. Increasingly over his career, he relied on layering and glazing in the final work to achieve his delicate psychological effects. Often he used a grey ground; on occasions it was warm brown or even orange. He liked costumes with touches of brilliant reds, pinks, blues or greens. His backgrounds are generalized, his bodies built up from dark to light in surfaces that are often richly tactile. He conveyed a strong sense of space kept in control by darkness. Often a single tightly focused detail, such as Gross’s scalpel in the Gross Clinic, grounded the emotional superstructure of his paintings in a sharply material universe.

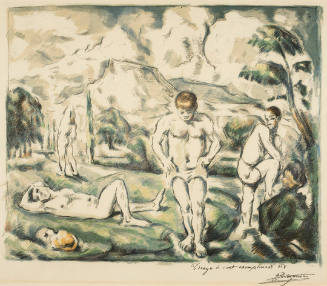

While oil painting was the major focus of Eakins’s life—though from 1875 to 1886, teaching may have come first—he also worked in other media. In the 1870s and 1880s he painted a number of works in watercolour, like his contemporaries on both sides of the Atlantic exploring the possibilities of the medium with tight work at first and then a gradual loosening of the forms (see fig.). The subjects of these watercolours are all lighthearted; they include scenes of baseball players, sailing, rowing and, with a historical focus unusual in his work, women spinning.

Eakins used sculpture early in his work as a study, most prominently in his extensive preparations for the paintings William Rush Carving his Allegorical Figure of the Schuylkill River (1877; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.) and Fairman Rogers Four-in-Hand (1879; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.), in which he modelled the figures in wax. He made several sculptural reliefs, including Arcadia (1883; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.) and the horses for two public monuments.

Eakins used the camera from as early as 1875, typically as a vehicle for study, but also to record his family and close friends. He assisted Eadweard Muybridge in his photographic study of men and animals in motion at the University of Pennsylvania in 1884, and later he conducted many photographic motion and anatomical studies, assisted by his students. [Elizabeth Johns. "Eakins, Thomas." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 8, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T024413.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms