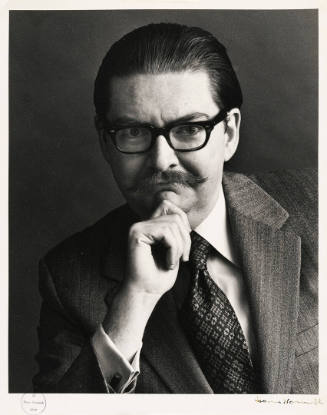

Alexander Calder

Alexander Calder

1898 - 1976

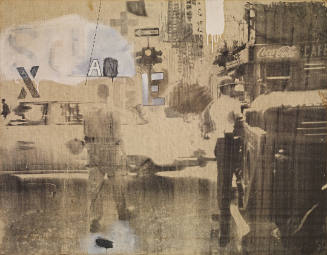

Sculptor, painter, illustrator, printmaker and designer, son of (2) Alexander Stirling Calder. He graduated from Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, NJ, with a degree in mechanical engineering in 1919. In 1923 he enrolled at the Art Students League in New York, where he was inspired by his teacher, JOHN SLOAN, to produce oil paintings. He became a freelance artist for the National Police Gazette in 1924, sketching sporting events and circus performances. His first illustrated book, Animal Sketching (New York, 1926), was based on studies made at the Bronx and Central Park Zoos in New York. The illustrations are brush and ink studies of animals in motion, with an accompanying text by the artist.

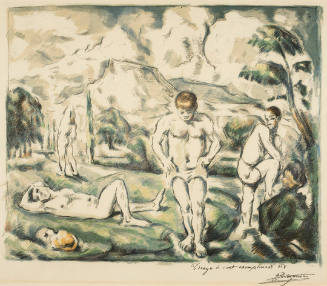

In 1926 Calder began his sojourns in Paris, where he attended sketching classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. He was particularly influenced by the inventive collages of JOAN MIRÓ and by the whimsical art of PAUL KLEE, to which he was introduced by Miró. In Paris Calder made wood and wire animals with movable parts and designed the first pieces of his miniature Circus (1926–32; New York, Whitney). Performances of this hand-operated circus helped to introduce Calder to the Parisian avant-garde and to potential patrons. From 1927 to 1930 he constructed figures, animals and portrait heads in wire and carved similar subjects in wood.

After visiting PIET MONDRIAN’s studio in 1930, Calder began to experiment with abstract constructions. He was invited to join Abstraction-Création in 1931 and was one of the few Americans to be actively involved with the group. In Paris in 1931 he exhibited his first non-objective construction, and in the following year he showed hand-cranked and motorized mobiles, marking the beginning of his development as a leading exponent of KINETIC ART. His major contribution to modern sculpture was the MOBILE, a kinetic construction of disparate elements that describe individual movements (e.g. Antennae with Red and Blue Dots). A Universe (1934; New York, MOMA) is an open sphere made of steel wire containing two smaller spheres in constant motion. With this motorized sculpture and related examples he demonstrated his indebtedness to astronomical instruments of the past, including the armillary sphere and the mechanical orrery. In addition, he used his knowledge of laboratory instruments from his college training in kinetics.

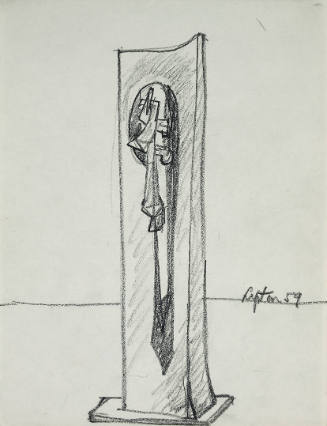

Calder remained fully committed to abstraction during the 1930s and was encouraged by European modernists. After an initial involvement with geometric elements and machine imagery, he introduced biomorphic forms into his kinetic sculptures. Both the painted constructions and the brightly coloured mobiles synthesized Constructivist methods and materials with abstract forms derived from Surrealist imagery. While his American contemporaries were only beginning to discover Constructivism, Calder was already exhibiting such work, both in the USA and in Europe. In 1938 he bought a farm in Roxbury, CT, and thereafter divided his time between visits abroad and longer periods of residence in the USA. He refined his wind-driven mobiles in subsequent years to produce elegant, space-encompassing abstractions of gracefully bending wires. Lobster Trap and Fish Tail (1939; New York, MOMA) is an example of the delicate balance that he achieved in deploying various forms from painted sheet metal and wire. His production of the 1930s included ‘plastic interludes’, which were circles and spirals performing on an empty stage during the intermissions of Martha Graham’s ballets. He also designed a mobile set for Erik Satie’s symphonic drama, Socrate (1936), held at the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT. In his later years he created costumes and set designs for various ballets and theatrical productions. Stabiles, large-scale constructions in cut and painted metal sheets, the first of which he created in the 1930s, appeared in substantial numbers from the 1950s. In his mature years his production included paintings, drawings, prints, book illustrations, jewellery and tapestries, all of which were composed of bold, abstract elements in primary colours. During the 1950s Calder continued to produce such mobiles as Big Red (1959; New York, Whitney) and 125 (1957; John F. Kennedy International Airport, New York), as well as producing new forms, including the Towers, wire constructions attached to the wall, with moving elements, and Gongs, metal pieces intended to produce various sounds. In the spring of 1954 Calder established a new studio and remodelled a house in Saché, France, where his family settled.

During the 1960s and 1970s colossal stabiles were commissioned for public sites around the world. Calder’s arching forms, dynamic surfaces and biomorphic imagery were the appropriate complement for the geometric regularity and severity of modern architectural complexes. Teodelapio, a stabile originally made for an exhibition in Spoleto, Italy, in 1962, served as a monumental gateway to the city. He designed Man for the World’s Fair, Montreal, in 1967. Stabiles of 15 m and more were installed in many American and European cities. The frequent allusions to animal forms in these stabiles can be traced back to his formative years and his interest in Miró and Klee’s fantastic imagery. One of the finest stabiles is Flamingo (1973), located at Federal Center Plaza in Chicago, IL. Positioned outside federal office buildings designed by Mies van der Rohe, it provides a visual transition between human scale and the colossal proportions of two monolithic skyscrapers that are adjacent. The red stabile complements the black steel and glass of the towers, and the curving forms counterpoise the severe geometry of the architect’s design. Like a giant bird poised on spindly legs with beak lowered to the ground, it attracts the attention of pedestrians and encourages movement beneath the space it occupies. Shortly before his death Calder completed a colossal stabile, La Défense, at the Rond Point de La Défense Métro station in Paris. After Calder’s death in 1976, a number of his public sculpture projects were installed with mixed results. Two notable examples are the giant mobile positioned in the atrium of the East Building at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. This project had to be redesigned and modified so that the elements would move. However, the mobile has presented many problems since its installation. Another unfortunate installation is Mountains and Clouds in the Hart Senate Office Building, known only in a small maquette at the time of Calder’s death. Calder’s allusions to fantastic animal forms in brightly painted sheets of metal attracted the attention of sculptors interested in whimsical creatures in polychrome. As the first American artist to achieve international success for his Constructivist/Surrealist sculpture, he exerted a strong influence on younger artists committed to abstraction. [Abigail Schade Gary and Joan Marter. "Calder." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 4, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T013131pg3.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms