George Grosz

George Grosz

German, 1893 - 1959

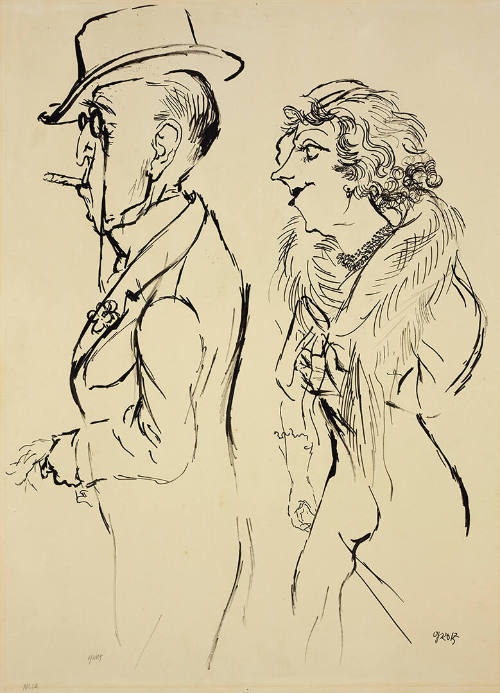

German painter, draughtsman and illustrator. He is particularly valued for his caustic caricatures, in which he used the reed pen with notable success. Although his paintings are not quite as significant as his graphic art, a number of them are, nonetheless, major works. He grew up in the provincial town of Stolp, Pomerania (now Słupsk, Poland), where he attended the Oberrealschule, until he was expelled for disobedience. From 1909 to 1911 he attended the Akademie der Künste in Dresden, where he met Kurt Günther, Bernhard Kretschmar (1889–1972) and Franz Lenk (1898–1968). Under his teacher Richard Müller (1874–1954), Grosz painted and drew from plaster casts. At this time he was unaware of such avant-garde movements as Die Brücke, also active in Dresden. In 1912 he studied with EMIL ORLIK at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Berlin. A year later he moved to the Académie Colarossi in Paris, where he learnt a free drawing style that swiftly reached the essence of a motif.

Before World War I, Grosz was completely apolitical. As a young man he sought refuge from the reality of his lower-middle-class circumstances in the fictitious world of cheap novelettes. He formed a predilection for modern adventures, assassinations, catastrophes, man-hunts and executions. In his early drawings Grosz rendered these subjects with a mixture of contradictory styles, which became a characteristic of his work. He was particularly influenced by the caricatures in satirical Jugendstil periodicals, copying their schematic, expressive gestures and hectic movements. Grosz was also impressed by the sublime gestures of historical academic painting, which he combined with exactly rendered elements from his immediate surroundings. His realism was also exemplified by his sensational reproductions of horrifying scenes.

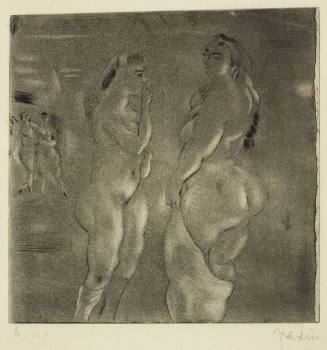

In 1914 Grosz, like many of his generation, volunteered for service in World War I. Six months later he was back in Germany. Although he was called up again in 1917, he was finally discharged as unfit for service after an episode involving violence and a short compulsory spell in a mental hospital. With the war his artistic approach changed fundamentally, taking its starting-point from his own experience of battlefields, death and destruction. Grosz had learnt to hate war and German militarism, as can be seen in the drawing Fit for Active Service (1916–17; New York, MOMA). Such feelings gave rise to his aversion for Germans, whom he saw as ugly, obese and degenerate: ‘I drew and painted from a spirit of contradiction, and attempted in my work to convince the world that this world is ugly, sick and mendacious’ (Kunstblatt, 1924). The war made Grosz into a misanthropist and a Utopian. In his art he fought against preoccupations of Wilhelmine society by uncovering their shadowy aspects of crime, murder and erotic licence. The sexual murder became a prominent motif, in which the combination of sexuality and violence was presented as a ritualization of the human quest for power, exemplified by political practice. Art became the vehicle of his pessimistic world view, reflecting a ruined world that manifested itself most trenchantly in the big city and its excesses.

In 1915 Grosz met Wieland Herzfelde (1896–1989) and Helmut Herzfelde (who soon after changed his name to JOHN HEARTFIELD) in Berlin. They became enthusiastic supporters of his uncompromising stance: a year later he changed his first name to George and began to work for Wieland Herzfelde’s left-wing literary–political journal Neue Jugend, and began to share a studio with Heartfield. Grosz frequented the Alte Café des Westerns, where he became familiar with revolutionary ideas. Out of opposition to the military scare campaign against Britain and intellectual affinity to the USA, he anglicized his name, which confirmed his anti-nationalist attitude. By giving his art a strong moral purpose, he intended to become the German Hogarth. In 1918 he listed the qualities that he wished his art to possess: ‘Hardness, brutality, clarity that hurts! There’s enough soporific music.’ In the same year he joined the German Communist Party.

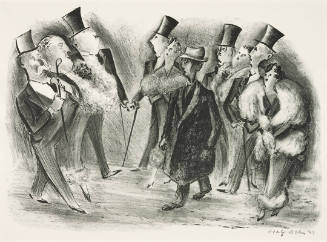

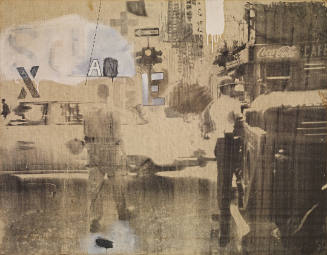

The war experience influenced not only his work’s content but also his style. In the painting Dedication to Oskar Panizza (1917–18; Stuttgart, Staatsgal.) he conveyed a hellish vision of the big city as a valediction to Wilhelmine society and its representatives: the composition is formed of simultaneous scenes overlapping in the painting and reproducing reality in a fragmentary form. In this aspect the influence of the Italian Futurists is clear; they had made a lasting impression on him through an exhibition held by Herwarth Walden in the Sturm-Galerie, Berlin, in 1913. An immense crowd of people—porcine grimacing faces, and stout citizens in bowler hats and pin-striped trousers between half-naked prostitutes, monarchists and clerics—flows between collapsing façades. They form a danse macabre against a blood-red background. ‘That this epoch is heading downhill towards destruction is my unshakable conviction’, he wrote to a friend in 1917.

Such a critical analysis of his time, together with its radical pictorial formulation, brought Grosz close to the Berlin Dada movement, which he joined in 1918 (see DADA, §4). In 1920, with Heartfield and OTTO DIX, he took part in the Erste Internationale Dada-Messe. As well as developing the technique of PHOTOMONTAGE, Grosz and Heartfield criticized the contemporary art world and the elevation of the artist to quasi-divine status. In a letter of opposition to the ‘Novembergruppe’ (Der Gegner 2, no. 8–9, 1921), Grosz called on artists to ‘collaborate in the building of a new human community, the community of working people’.

Grosz made his contribution towards realizing this goal by engaging with contemporary events through his works. For him Dada was the expression of a specific political stance. He remained politically committed even when he left Dada and turned to a realistic style of painting in the 1920s, in keeping with the spirit of the decade. During this period Grosz became internationally recognized as one of Germany’s most significant critical artists. The antagonisms of artistic and political life in the Weimar Republic found an extreme form of expression in Grosz’s work. Grosz himself was torn between a partisan, rationalist attitude and a passionate, reckless craving for the feverish pleasures of the 1920s, between basic Communist convictions and a longing for the USA. In his work he created a portrait, with acerbic cynicism, of the manners of the Weimar period, developing a new artistic idiom. He characterized the age in terms of the class society and invented specific figures who stood for the new classes and economic interests in German society. A few signs suffice to enable the artist to mark out a particular temporal and social context, and to indicate class and group affiliations: war cripples are depicted beside ragged soldiers, fat, cigar-smoking bourgeois figures and businessmen with monocles, suits and homburgs. In 1926 Grosz produced his major work, the Pillars of Society (Berlin, Neue N.G.). He depicted the representatives of the ruling class—press publishers, nationalists, monarchists and clerics—as a class of brainless and amoral people and held them responsible for the reactionary spirit, the hypocrisy and the beginnings of renewed warmongering in Germany. Grosz launched his most vicious attacks on society after World War I in his drawings: in 1920 the first two collections were published by Wieland Herzfelde’s Malik-Verlag. In 1928 the collection Background, which contained the drawing Shut Your Mouth and Keep on Serving, showing Christ on the cross wearing a gas-mask and soldiers’ boots, brought an accusation of blasphemy: the case continued until 1933. As well as producing portfolios of drawings, Grosz also illustrated works by such writers as Alphonse Daudet.

Grosz’s political commitment and increasing popularity brought him into lively contact with the cultural élite of the time, for example Kurt Tucholsky, Erwin Piscator, Josef von Sternberg and Bertolt Brecht. As conditions became more stable he gained a certain standing and was adopted by the gallery of Alfred Flechtheim in 1925. However, his attitude towards the class struggle was thereby blunted. He subsequently received portrait commissions from personages of the time (e.g. portrait of the poet Max Herrmann-Neisse): he carried these out using a glazing technique borrowed from the Old Masters, which he had seen Dix using in Dresden. In these portraits Grosz neither caricatured nor poured scorn on his subjects. On the contrary, he rendered physiognomies marked by fate, displaying subtle psychological insight and employing a form of realism that placed him among the exponents of NEUE SACHLICHKEIT.

With the increasing strength of the Nazis, Grosz came under renewed outward pressure and considered, as he had done before, emigrating to the USA, the free land of his youthful dreams. He was encouraged in this by the early recognition accorded to his work there, and by a visiting professorship at the Art Students League, New York, in 1932. He continued to teach there until 1955. In 1933, shortly before Adolf Hitler’s seizure of power, he left permanently for the USA. Under the influence of new, positive impressions, and because he had lost his faith in the strength of the masses, he turned away from political propaganda and lost his mordant style. Almost affectionately, he caricatured New York types and painted landscapes from nature. In 1958, with his collages that point in some ways towards Pop art, he reverted to Dada techniques. In 1959 he returned to West Berlin, where he died soon afterwards. [Ursula Zeller. "Grosz, George." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 8, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T035094.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms