Charles Sheeler

Charles Sheeler

1883 - 1965

American painter and photographer. He studied at the Philadelphia School of Industrial Design from 1900 to 1903, and then with William Merritt Chase at Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (1903–6). In 1906 he exhibited in a group exhibition at the National Academy of Design, New York. From 1908 to 1909, while visiting Europe, Sheeler and Morton Schamberg discovered the architectonic painting structure in the frescoes of Piero della Francesca at Arezzo, in the work of Paul Cézanne and in works by Henri Matisse and Georges Braque; Sheeler exhibited paintings influenced by Cézanne and by Synchromist colour abstraction at the 1913 Armory Show.

Early Analytical Cubist paintings by Picasso were a decisive influence on Sheeler’s art from 1910 to 1920, for, like contemporary artists and writers inspired by Van Wycks Brook’s notion of a ‘usable past’ (‘On Creating a Usable Past’, The Dial, 11 April 1918, pp. 337–41), Sheeler learnt to discover abstract form in older native subject-matter, particularly in the imposing stone barns of Bucks County, PA; in the conté drawing Barn Abstraction (1917; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.) he rendered architecture with flattened blueprint-like geometry. Together with Schamberg, Sheeler rented a Bucks County farm cottage from anthropologist Henry Chapman Mercer (1856-1930) from c. 1910 and took pleasure in Mercer’s pioneering collection of old household and farm tools.

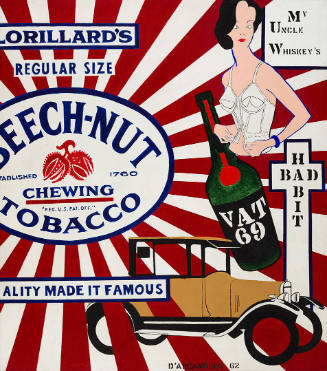

In the next decade Sheeler trained as a commercial photographer to support himself as a painter; by 1915, encouraged by Alfred Stieglitz, he began to consider photography as an equally valid medium of personal expression. Sheeler’s silver gelatin prints of the early American interior of his farm cottage (examples New York, MOMA; New York, Met.; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.; Fort Worth, TX, Amon Carter Mus.) won prizes in the John Wanamaker Company’s 13th annual photography exhibition (1918), whose jurors included Stieglitz. Stieglitz’s friend, Marius De Zayas, who held exhibitions of African sculpture and modern art in his New York galleries, organized Sheeler’s first one-man show in 1920 and exhibited his photographs. Sheeler regarded himself as an avant-garde artist in a wide range of media and depicted the graphic shapes of objects from the American past as the native correlative to Cubism; for example the conté drawing House and Stairs (1917; New York, Harvey and Françoise Rambach priv. col.) and Objects on a Table (1924; Columbus, OH, Mus. A.). He was also influenced by Robert Coady (1876–1921) and Coady’s enthusiasm for popular industrial culture, documented in The Soil, the magazine published in New York (1916–17) for which Coady was art editor, and later by his friends, writer Matthew Josephson (1899–1978), whose articles praising billboards and machinery appeared in Broom in 1922 and 1923, and poet William Carlos Williams (1883–1963), whose search for the roots of American culture paralleled Sheeler’s interest in American subjects.

Between 1915 and 1921, at the home of patrons Walter and Louise Arensberg, Sheeler came into contact with the iconoclastic machine-derived images of Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia and other participants in New York Dada including Charles Demuth and Joseph Stella. Sheeler’s Self-portrait (1923; New York, MOMA), a conté drawing in which the artist represented himself as a Dadaist mechanomorph in the image of a telephone, is his manifesto for an impersonal art, one that annexes photography’s finish and verism.

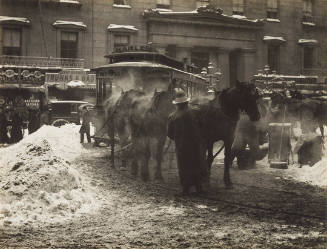

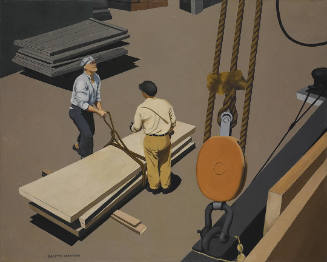

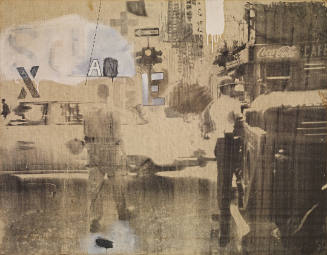

Throughout his life, Sheeler took on photographic commissions. He collaborated with Paul Strand on a film, Manhattan (1920–21), photographing the city and its skyscrapers. Between 1923 and 1932 he worked as a freelance photographer for Vogue and Vanity Fair. In 1927, the advertising firm N. W. Ayer arranged a Ford Motor Company commission to photograph the River Rouge, MI, factory. The Ford Plant photographs of industrial architecture and machinery brought acclaim in artistic circles. Industry, a photomontage created for the Museum of Modern Art’s Murals by American Painters and Photographers exhibition of 1932, and preparatory photographs for the painting series, Power—a Portfolio by Charles Sheeler, commissioned by Fortune (xxii/6, 1940), blur the divisions between commercial and personal photography and between Sheeler’s photography and his painting. Precisionist works of the 1920s, including New York (drawing, 1920; Chicago, IL, A. Inst.), Offices (1922; Washington, DC, Phillips Col.; for illustration see PRECISIONISM) and particularly Upper Deck (oil on canvas, 1929; Cambridge, MA, Fogg), document Sheeler’s self-defined ‘dividing line’ in his approach to his art. Sheeler wanted to merge photography and painting, and sought to ‘remove the method of painting… from being a hindrance in seeing’ (1939 exh. cat., p. 10). During the 1930s Sheeler exhibited regularly at the Downtown Gallery, New York. Such works as View of New York (1931; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.) with photographic subjects are translated from photographs, and Sheeler continued to allow his photographs to influence his paintings throughout the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s when he painted geometric semi-abstractions, resembling photographic transparencies superimposed off-register, for example Manchester (1949; Baltimore, MD, Mus. A.). Sheeler’s innovative subjects define an iconography for 20th-century utilitarian industrial themes, an American ‘machine age’ aesthetic. He wrote, ‘Industry concerns the greatest numbers…. The Language of the Arts should be in keeping with the Spirit of the Age’ (Sheeler, 1937).

Throughout his career, Sheeler chose urban and factory subjects and their pre-industrial roots, barns and the interiors of rooms in which he lived, for example Home Sweet Home (1931; Detroit, MI, Inst. A.) and American Interior (1934; New Haven, CT, Yale U., A.G.), which he furnished with early American and Shaker furniture, a taste that he had pioneered by the 1920s. He paired early American objects with examples of contemporary design, prizing both as examples of economy and functionalism. Early American decorative arts and machine-derived motifs were the inspiration for the fabric, tableware and glassware that Sheeler designed between c. 1933 and 1936, the style of which evokes the subjects and structure of his paintings.

Sheeler’s aesthetic defines Precisionist sensibility of the 1920s in American painting (see PRECISIONISM). Precisionist painters George Ault (1891–1948), Charles Demuth, Elsie Driggs (1898–1992), Louis Lozowick (1892–1973), Ralston Crawford and Niles Spencer shared Sheeler’s interests in an iconography based on utilitarian subject-matter, including factories and the cityscape. Although they tended towards a realist style, impersonal paint handling and strongly geometric compositions deriving from Cubism, they looked to European radical art, substituting realism for abstraction and consciously choosing native subjects. From 1942 to 1945 Sheeler worked as a photographer for the Museum of Modern Art. He soon, however, returned to painting as his preferred medium but abandoned it after suffering a stroke in 1959. [Susan Fillin-Yeh. "Sheeler, Charles." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 11, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T078127.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms