Winslow Homer

Winslow Homer

1836 - 1910

American painter, illustrator and etcher. He was one of the two most admired American late 19th-century artists (the other being Thomas Eakins) and is considered to be the greatest pictorial poet of outdoor life in the USA and its greatest watercolourist (see fig.). Nominally a landscape painter, in a sense carrying on Hudson River school attitudes, Homer was an artist of power and individuality whose images are metaphors for the relationship of Man and Nature. A careful observer of visual reality, he was at the same time alive to the purely physical properties of pigment and colour, of line and form, and of the patterns they create. His work is characterized by bold, fluid brushwork, strong draughtsmanship and composition, and particularly by a lack of sentimentality.

1. Early career, to 1872.

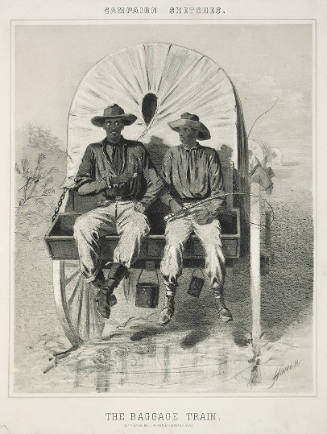

Homer was the second of three sons of Charles Savage Homer, a hardware importer, and Henrietta Benson Homer, a gifted amateur watercolourist. Brought up in Cambridge, MA, where he attended school, he had an active outdoor boyhood that left a lifelong liking for the country. An independent, strong-willed young man, he showed an early preference for art and was encouraged in his interest by both parents. Like a number of self-educated American artists, Homer was first known as an illustrator. At 19 he became an apprentice at the lithographic firm of J. H. Bufford in Boston, where he developed a basic feeling for draughtsmanship and for composing in clear patterns of dark and light. When he completed his apprenticeship in 1857, he was determined to support himself as a freelance illustrator. His first illustrations—scenes of life in Boston and rural New England—appeared in Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, the noted Boston weekly. In 1859 he moved to New York and became an illustrator for Harper’s Weekly magazine and for various literary texts, an activity that occupied him intermittently to 1887; among the authors he illustrated were the poets William Cullen Bryant, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Shortly after arriving in New York, he decided to broaden his artistic training. He attended drawing classes in Brooklyn, went to night school at the National Academy of Design and for a brief time had lessons in oil painting from the French genre and landscape painter Frédéric Rondel (1826–92). During the Civil War he went south with the Union Armies, serving as artist–correspondent for Harper’s. His illustrations, showing the daily routine of camp life, are marked by realism, firm draughtsmanship and an absence of heroics. They were among the strongest pictorial reporting of the war.

After the war Homer began to concentrate on oil painting. These early oils, inspired by wartime scenes, are sober in colour and reveal the influence of his work as an illustrator in their grasp of the simple, telling gesture and the clarity of tone. They were instrumental in his election to the National Academy at the age of 29. His masterpiece of this period is Prisoners from the Front (1866; New York, Met.), which shows a Union officer confronting a group of Confederate prisoners in the midst of a devastated Virginia landscape. Shown at the National Academy of Design in 1866, it created a sensation and was hailed as the most powerful and convincing painting to have come out of the Civil War; it was singled out for praise at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867.

Late in 1866 Homer made his first trip to Europe, spending ten months in France. In Paris he shared a studio in Montmartre with Albert Warren Kelsey, a friend from Massachusetts, and spent time in the countryside. His paintings from this period show the influence of the Barbizon school, especially the work of Jean-François Millet. Possibly as a result of seeing the work of such progressive French landscape painters as Eugène Boudin, on his return to New York in the autumn of 1867, Homer lightened his palette, and his touch became somewhat freer (e.g. Long Branch, New Jersey, 1869; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.). Although New York was his winter home for over 20 years, he never painted it and seldom illustrated it. The outdoor world furnished the main content of his art for the rest of his life. From late spring into the autumn he worked in the country, mostly in New England but on occasion in New York state and New Jersey. These summer months provided material for almost all his early paintings and illustrations. While in a general sense he was continuing a native genre tradition initiated in the 1830s by William Sidney Mount and still being carried on by such popular painters as John George Brown, Homer’s content marked a departure from the sentimentalism of the old school. Within a naturalistic style he combined authenticity of images and a reserved idyllicism. Rural children at play (e.g. Snap the Whip, 1872; Youngstown, OH, Butler Inst. Amer. A. and New York, Met.; see fig.) and handsome young people at leisure (e.g. a Game of Croquet, 1866; New Haven, CT, Yale U. A.G.) were his subjects, presented within clear, firm outlines and broad planes of colour.

2. Middle years, 1873–82.

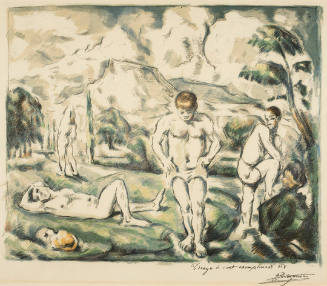

By 1873 Homer was at a critical point in his career. Although his ability was recognized, he sold few oils, and he derived little sense of achievement from his work as an illustrator, describing it as a form of bondage. Responding perhaps to the growing interest by collectors and critics for watercolours by American artists—undoubtedly stimulated by an immensely successful exhibition of English watercolours shown at the National Academy in 1873—Homer took up the medium. Although he had often used wash drawings in preparation for his wood-engravings and lithographs, it was in the summer of 1873, spent at the fishing port of Gloucester, MA, that he explored the medium seriously for the first time. He exhibited the summer’s work at the American Society of Painters in Watercolors in the spring of 1874 and became a member in 1877. Critics praised his originality, while at the same time severely criticizing him for what they called his crude colour and lack of finish. The translucency of watercolour against the white paper made an immediate difference in his colour, which attained a new clarity and luminosity (see fig.). Thereafter, watercolour became an increasingly important part of his artistic expression. It became the medium in which he experimented with place and subject, and light and colour, the results of which he later embodied in oil. In time it was the medium in which he became America’s undisputed master.

During the 1870s Homer’s art grew steadily in strength and skill. With a growing command of plein-air light and its relation to form and space, his compositions became more complex and subtle. His works of the 1870s were much preoccupied with women, usually shown engaged in genteel activities. There were, however, exceptions: among them a series of paintings of black people in Virginia. Typical is the Cotton Pickers (1876; Los Angeles, CA, Co. Mus. A.), in which he imbues the figures with dignity and physical beauty, unlike the condescending images of blacks created by many of his contemporaries.

Unlike other American artists who flocked to Paris during the 1880s, Homer went to England in 1881 and settled in Cullercoats, a fishing village and artists’ colony near Tynemouth, Tyne & Wear, an experience that had a profound effect on his art and his life. For the 20 months of his stay he devoted himself almost entirely to watercolour painting, mastering a range of academic techniques and making scores of pictures of the fisherfolk, particularly the women. The first works he produced were narrative and picturesque, closely related to the then-popular fishing subjects of The Hague school artists and to European peasant themes in general. His images gradually became more iconic, revealing a new undertone of seriousness and emotion. With such watercolours as Inside the Bar (1883; New York, Met.), Homer arrived at the subject that would concern him for the rest of his life: Man’s struggle with Nature.

3. Late works, 1883–1910.

In the autumn of 1882 Homer returned to New York City. A little more than a year later he settled permanently in Prout’s Neck, ME, a lonely, rocky promontory on the Atlantic coast. He built a studio on the high shore, near the ocean, where he lived alone. His centre of interest shifted from inhabited to wild nature—to the sea and the wilderness, and the men who were part of them. From this time his art changed fundamentally; the idyllic worlds of leisure and of childhood pleasures disappeared, and women appeared less and less. The first product of this change was a series of sea paintings, among them the Fog Warning (1885; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.) and Eight Bells (1886; Andover, MA, Phillips Acad., Addison Gal.), in which the recurring theme was the perils of the sea and the drama of Man’s battle with it. Neither literary nor sentimental, their power is conveyed in purely pictorial terms. They were immediately successful, commanding high prices, and they established Homer’s reputation as one of the foremost American painters. While painting his sea-pieces, Homer embarked on a new medium, etching. He etched eight plates between 1884 and 1889, seven of which were based on his sea paintings and his English watercolours (for illustrations see Goodrich, 1968, pls 90, 92, 94, 96, 98, 100, 102–3).

Although Homer’s few recorded remarks on art express a purely naturalistic viewpoint, his images are metaphors of nature, confronting the question of mortality. In one of his greatest paintings, the Fox Hunt (1893; Philadelphia, PA Acad. F.A.), the primitive struggle for survival is played out between a fox, normally the predator, trapped in deep snow, and a flock of birds descending from the sky for the kill.

The sea had been a subject of Homer’s from the time he had worked at Gloucester in the early 1870s. In 1890 he began a series of pure seascapes that became his best-known work (e.g. Sunlight on the Coast, 1890; Toledo, OH, Mus. A.; The Northeaster, 1895; New York, Met.). Critics praised these pictures for their ‘virility’ and ‘Americanness’. Monumental in scale, they were painted with broad brushwork and great plastic strength. The power, the danger, the loneliness and the beauty of the sea are evoked with an immediacy of physical sensation that places them among the most powerful modern expressions of Nature’s force. The northern wilderness was also a favourite theme, but, unlike the earlier Hudson River school painters whose approach combined spectacular Romanticism and meticulous literalism, Homer expressed the exhilarating experience of this wild and unspoiled world through expressive brushwork and resonant colour, as in his watercolour On the Trail (1892; Washington, DC, N.G.A.).

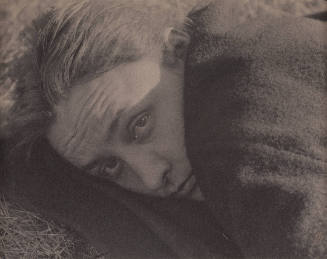

In his later watercolours, however, executed on vacations away from Prout’s Neck, Homer attained his purest artistic values. He brought to the medium a basically new style: painterly handling and saturated colour. An outdoorsman all his life (see SPORTING SCENES, §4), he took a fishing vacation almost every year, to the Adirondack Mountains, NY, and Quebec or to Florida, the Bahamas or Bermuda. The change of scene together with the lighter medium stimulated a more spontaneous expression. In oil, his touch was powerful, exploiting the weight and density of the medium; in watercolour, it was full of sensuous nuance. His watercolours express a private and poetic vision that otherwise found no place in his art; for example Adirondack Guide (1894; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.) and Sloop, Nassau (1899; New York, Met.) contain the pure visual sensation of nature. Painted on the spot, with fluid, audacious brushwork and full-bodied colour, composed with unerring rightness of design and linear beauty, Homer’s later watercolours have had a wide and liberating influence on much subsequent American watercolour painting by such diverse artists as John La Farge, John Marin and Andrew Wyeth.

Although he achieved recognition early, Homer never had the financial success of an international favourite such as John Singer Sargent. In old age he was generally regarded as the foremost living American painter, and he received many awards and honours. By the last years of his life, more of his works were in public collections than those of any other living American artist. [Helen A. Cooper. "Homer, Winslow." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 8, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T038730.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms