Asher B. Durand

Asher B. Durand

1796 - 1886

American painter and engraver. He played a leading role in formulating both the theory and practice of mid-19th-century American landscape painting and was a central member of the HUDSON RIVER SCHOOL. Five years older than Thomas Cole, he matured considerably later as an artist. After an apprenticeship (1812–17) with PETER MAVERICK, he began his career as an engraver, attaining eminence with plates after John Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence (1820–23) and John Vanderlyn’s Ariadne (1835), the latter so accomplished that the chronicler William Dunlap claimed it would win Durand immortality as an engraver. As with many contemporary artists, his training was based on drawing, an experience that influenced his insistence on the importance of outline and precise rendering.

Durand first took up painting in the 1830s, producing portraits of distinguished Americans and occasional history pieces such as the Capture of Major André (1834; Worcester, MA, A. Mus.). Perhaps inspired by the success of Thomas Cole, Durand began exhibiting landscape paintings in 1837; Cole’s influence is particularly apparent in allegorical landscapes such as the Morning of Life and the Evening of Life (both 1840; New York, N. Acad. Des.). This literary or didactic strain was present in Durand’s work until the early 1850s; works such as Thanatopsis (1850; New York, Met.) embody the ‘sister arts’ concept that provided American painters with a literary justification for the emergent genre of landscape. At the same time, however, there was a growing interest in precisely observed portraits of American nature.

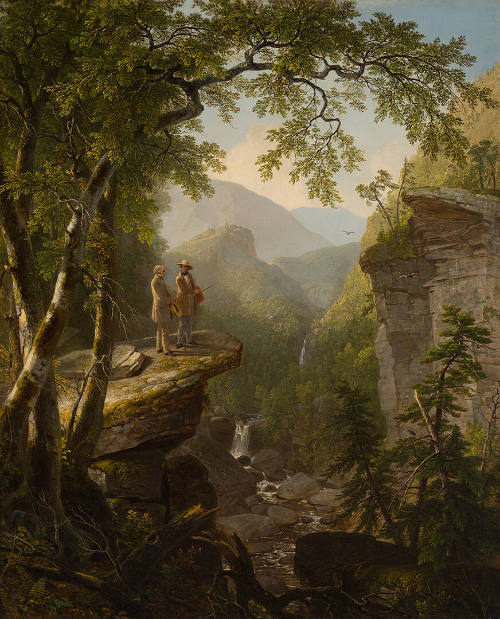

Durand was credited by his son and biographer, John Durand, with painting the first finished oil landscape studies from nature. Landscape with a Beech Tree (1844; New York, NY Hist. Soc.), a highly finished work, is his first such known study. Increasingly thereafter he advocated direct study from nature, finding a more formal expression of his beliefs in John Ruskin’s Modern Painters (1843–60). Study from nature, though it carried enormous authority for Hudson River school painters, served for Durand only as the basis for constructing finished compositions that incorporated idealized or composite types distilled out of nature’s variety (see fig.). He distinguished between the imitative and representative, or typical, character of art. His ‘Letters on Landscape Painting’, written in 1855 for THE CRAYON (a Ruskinian art journal published in New York), constitute a key statement of landscape painting theory in mid-19th-century America, namely that nature served as the arbiter of artistic truth. Such Ruskinian ideas, however, were received by Durand within the context of a native idealism and faith in the intuitive apprehension of nature’s inherent beauty and goodness.

By the middle of his career Durand had developed a landscape idiom that allowed him to reconcile the naturalism of direct observation with nationalistic themes. In compositions such as the Advance of Civilization (1853; Tuscaloosa, AL, Warner Col., Gulf States Paper Corp.), Durand expressed a progressive vision of national destiny through the organization of the landscape scene itself, beginning with the Indians in the foreground wilderness and moving through the stages of national development defined successively by wagon, steamboat and canal, telegraph system and railway.

In works such as the View of the Hudson Valley (1857; Ithaca, NY, Cornell U., Johnson Mus. A.), Durand employed established compositional formulae in landscape painting to imbue American wilderness scenes with a stable harmony reminiscent of the 17th-century classical landscapes of CLAUDE LORRAIN. His concern with balanced composition, graduated movement into the distance and refined tonal modulation (through subtle gradation of local colour) also points to the influence of Claude (see fig.). (As he later wrote, Durand ‘visited Europe…lured above all by the glory of Claude’s famous productions’.) Such an approach gave cultural validation to American nature as a subject for art.

By the second quarter of the 19th century Durand’s urban patrons, such as Luman Reed and Jonathan Sturges, were developing important collections of American art. It was Sturges who commissioned Kindred Spirits (1849), which shows the poet William Cullen Bryant admiring a Catskill gorge with Thomas Cole, who had died the previous year. The painting serves as an artistic testament to the importance of wilderness in the formation of national identity. Durand also produced idyllic scenes of domesticated nature, works that breathed an air of reverence and nostalgia for lost origins that was deeply appealing to Americans in a period of rapid economic and social change.

After the death of Cole in 1848, Durand was generally acknowledged as the foremost landscape painter in America, his work embodying many of the principal aesthetic and moral values ascribed to that genre by his contemporaries. Until his retirement in 1878, Durand followed a familiar pattern for many American landscape painters—winter residence in New York, alternating with periodic sketching trips to the Catskills, Adirondacks and other sparsely settled mountainous regions of the north-eastern United States. He travelled to Europe only once, from 1840 to 1841. His example for younger artists, his success with wealthy urban patrons and his term as president of the National Academy of Design from 1845 to 1861 all conferred legitimacy on landscape painting. [Angela L. Miller. "Durand, Asher B.." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 8, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T024145.]

Person TypeIndividual

Terms

French, 1864 - 1901